Reading Time: 4 minutes

Indian festivals based on marriage, the observance of Karwachauth, of Teej, Chhath, Vat Savitri, etc. are all centred on longevity – not of women but men. Patriarchy is insidiously injected in the guise of such festivals, opines Pratima. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Folktales and fairytales form an indispensable part of any culture. They serve to act as a mirror of the basic societal structure. The folktales often reiterate the ideas that a culture endorses. Folktales and legends assume so much importance in our country that many a festival is based on them.

It is that jovial time of the year when several festivals related to our mythology and folktales are celebrated with gusto and vigour. With Karwachauth festivities on a high and Diwali round the corner, there is zest in an Indian household, despite the COVID-19 crisis. Karwachauth with its fascinating mehndi (henna) designs, dazzling jewellery, gifts, red sarees, lehengas, bangles etc. is the centre of attraction for most married women. Originally celebrated in Punjab, Haryana, Delhi and some parts of Uttar Pradesh, the festival gained momentum in all parts of India, with its incorporation in several Bollywood movies. Karwachauth became a craze among women after the release of the epic movie Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaenge (1995) and I remember how as an adolescent, with no earlier familiarity with the much romanticised Karwachauth vrat (fast), I pined to wear a red saree and enact that chalni (sieve) scene with my husband when I got married.

When I grew up, I comprehended that the festival that is projected as being utterly romantic and which is supposed to be an Indian version of Valentine’s Day, with many young unmarried women keeping a fast for their boyfriends/ future husbands, has several other not so romantic and dreamy connotations. I realised that Indian festivals based on marriage, the observance of Karwachauth, of Teej, Chhath, Vat Savitri, etc. are all centred on longevity – not of women but men. Patriarchy is insidiously injected in the guise of such festivals.

Several folktales are related to the Karwa fast. One such tale suggests that the first Karwa Vrat was kept by the Goddess Parvati for the longevity of her husband Shiva. Really? Does the great God Mahadeva, the immortal Destroyer need a fast to sustain in the Universe?

Several folktales are related to the Karwa fast. One such tale suggests that the first Karwa Vrat was kept by the Goddess Parvati for the longevity of her husband Shiva. Really? Does the great God Mahadeva, the immortal Destroyer need a fast to sustain in the Universe? Some other legends related to Karwachauth are that of a woman Karwa, whose husband was caught by a crocodile while bathing in a river, and when the pativrata (devoted to husband) woman threatened to curse Yama, the God of Death, he sent the crocodile to hell and saved the life of Karwa’s husband.

In another tale, Queen Veeravati, who was the only sister of seven loving brothers, was desperate for moonrise to break her fast. The brothers anguished to see their sister thirsty and hungry created the image of mirror in a peepal tree and Veeravati taking it for the real moon broke her fast. And her husband immediately died. Later, Goddess Parvati intervened and saved her husband only on one condition that she will rigorously observe another day of fast with no mistakes. Veeravati does that and her husband comes back to life. Both these tales send the women some strong messages—that women should be dedicated and devoted to their husbands and if they do that even the Gods will fear them or come down to help them, that women should observe the fast with extreme caution and care and starve themselves till it is the right time to break their fasts else their husbands would die, that the longevity of the husband is far more important than that of a woman.

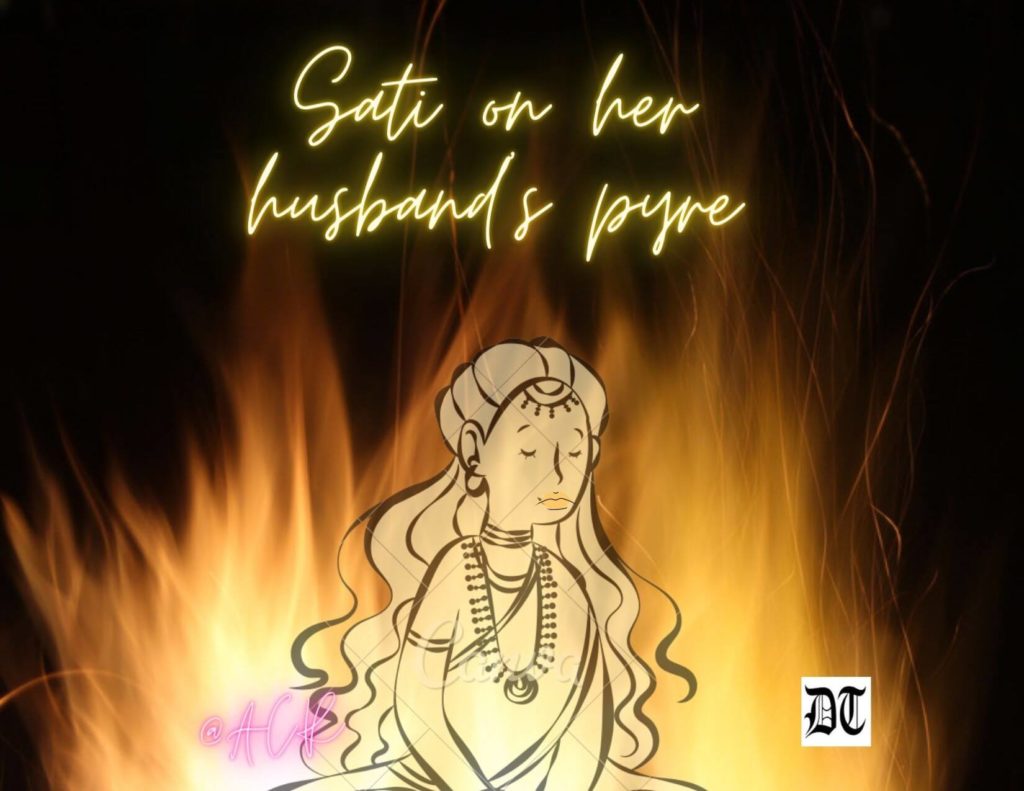

In times when women were confined to domesticity and had no livelihood to support themselves, the life of the breadwinner, the pati-parmeshwar was perceived to be far more important than her life by society. In earlier times, if a woman became a widow, she had to spend the rest of her life accursed in some white cloth or she was burnt as a Sati on her husband’s pyre.

In times when women were confined to domesticity and had no livelihood to support themselves, the life of the breadwinner, the pati-parmeshwar was perceived to be far more important than her life by society. In earlier times, if a woman became a widow, she had to spend the rest of her life accursed in some white cloth or she was burnt as a Sati on her husband’s pyre. But it is the life of the husband, who could remarry and who could enjoy all privileges of a happy life despite his marital status, which was perceived to be of utmost importance. From such thoughts, perhaps emanate fasts like Karwachauth.

In the twenty-first century, with more and more women being economically independent, such fasts are observed under the garb of choice and freedom. But perhaps in the choice of such women lies the generation down the fear of some mishap if the fast is not observed, some internalised misogyny which they have inhaled in the patriarchal air they have been raised into.

While even I cannot ignore the resplendent jewellery and dress up along with the romantic Karwa moon which symbolises marriage and love, the observance of fast and related rituals come within my range of scrutiny. Tradition is and should be transmitted from one generation to the other, but superstition should not.

Visuals from Different Truths