Reading Time: 19 minutes

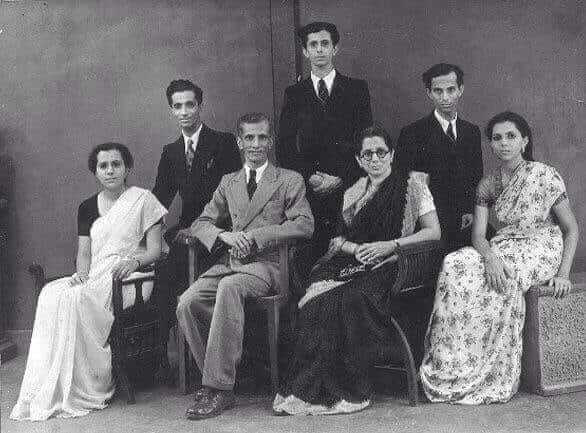

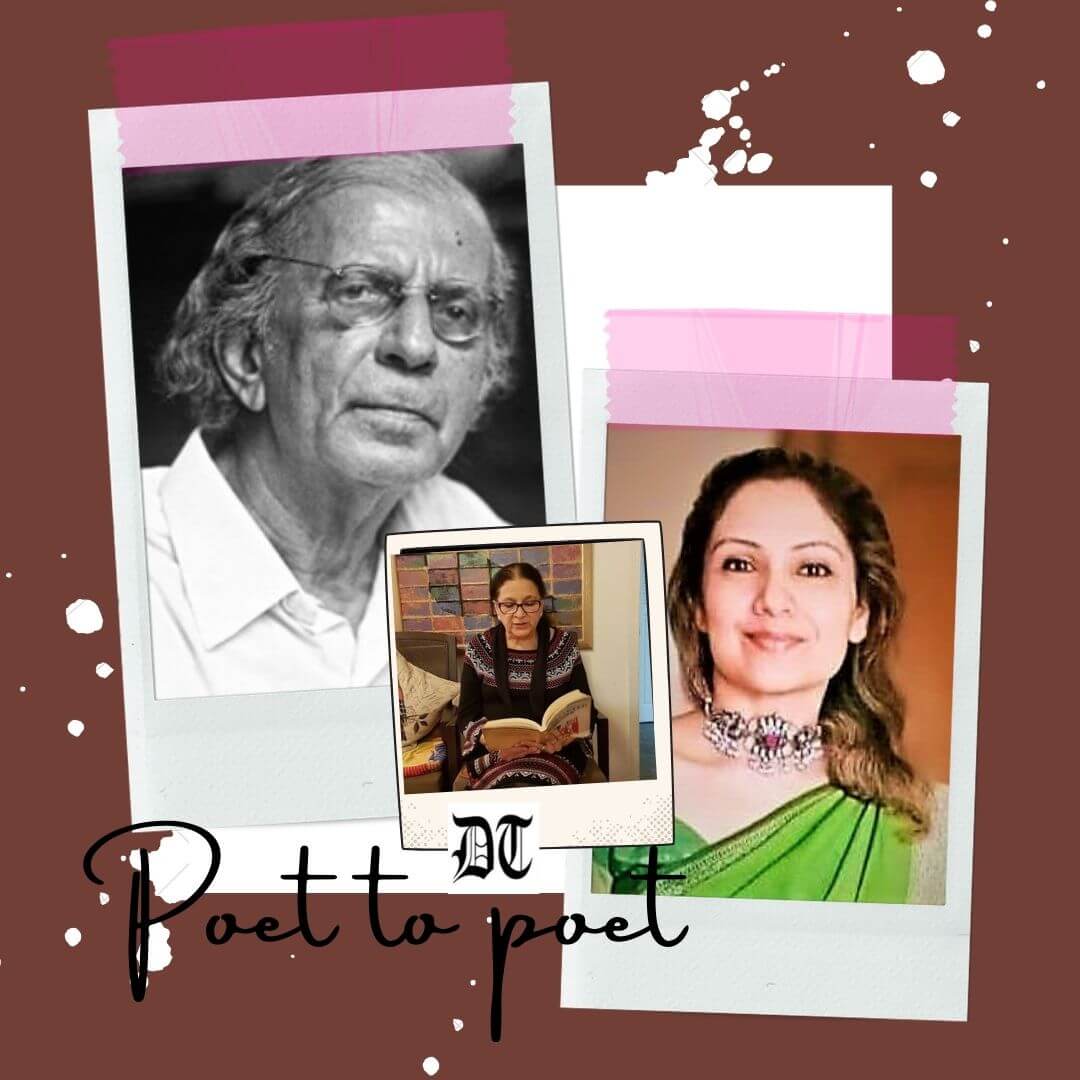

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca, daughter of the prominent poet, Nissim Ezekiel, quotes her father saying, “…I was the extension of his soul.” She adds, “The poems I write to pay tribute to him….” She pours her heart out, telling us about the deep bond with her poet father, his life, struggles, and accolades, in a candid interview with Urna. An exclusive for Different Truths.

The words of Steve Jobs saunter up and down the alleys of my mind: “you can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards”. And as I look back, to understand how and when I started to feel the initial, embryonic stirrings of poetry, within the folds of my own being, one poem almost jumps out, from the labyrinth of my memories.

Sitting atop a high mountain of stunning poems, one piled up on another. A veritable mountain of all the poems, I was taught at school. And this poem not only blew my mind, but it forever changed the way a young girl in class VIII viewed poetry. Along with some of my understanding of what makes for piercingly powerful poetry.

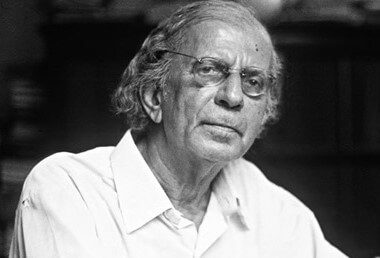

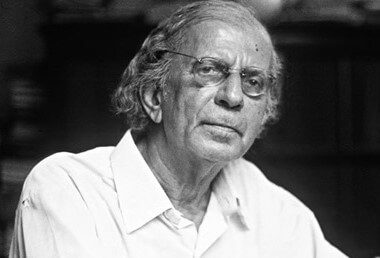

Yes, I am talking about the iconic ‘Night of the Scorpion’ by Nissim Ezekiel. Widely taught in schools across India, and an integral part of NCERT and ICSE English textbooks.

Do join me dear friends, as I chat with Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca, the widely published and renowned poet, fiction writer and of course, the daughter of the late poet, Nissim Ezekiel. To understand and take a closer look at ‘the Father of post-independence, contemporary Indian English poetry’, as well as the doting ‘Daddy’ that he was to another poet in the making.

Urna: You were the first born, the apple of your father’s eyes. Help us, his fans, and readers to see Nissim Ezekiel, an icon and the father of Indo-Anglian poetry through your eyes – the up, close, and personal daughter’s gaze. How was he, the loving, doting father? And the bond between the two of you?

Kavita: Firstly, let me thank you for the invitation to an interview about my father, the late Nissim Ezekiel’s contribution to Indo-Anglian Poetry. As his daughter, it is an honour and a privilege for me to speak about him. Preserving his legacy is a matter of not just pride, but also comes with a great responsibility, sometimes more important to me than my own writing.

“It doesn’t matter who my father was; it matters who I remember he was.” – Anne Sexton.

To the world, my father was the poet, Nissim Ezekiel. To me, he would be the man I would call Daddy, all my life. We do not choose the family into which we are born, but are placed there by, what some may, call Destiny or Fate, but by what I believe, is an all-knowing God, a God whose plans are perfect.

I heard from so many friends and relatives and of course repeatedly from my mother, that my father was delighted at my birth. He was a very fair-minded man and loved all his children equally, but being the first born, I was just a little more special to him, in the way that first-born children usually are. He did dote on me and was a truly indulgent father. We had a special bond as we both shared a passion for teaching, poetry, and life itself. When I walked with him to the nearby store to buy a bottle of Vino Royale (the cheapest wine in those days), I would ask him what the occasion was, and he would reply, “To celebrate Life!”. We did not buy wine often, but when we did, he had a special spring in his step. My mother was puzzled at his kind of philosophy of life. She was a practical and down-to-earth person.

Due to family complications, I would live with him at my grandmother’s house, from the age of ten, until I got married. It was difficult to be separated from my mother, though I saw her every Sunday, when she would spend the day with us, bringing goodies that my father and I loved. Living with my father, and caring for him and all his physical needs, deepened our bond. I would change the bed linen, tidy his clothes cupboard, dust, and organise the numerous books, and go shopping with him to buy those colored khadi kurtas he preferred to wear. The only thing he forbade me from doing was rearranging his writing desk. We joked that there was a sort of method in his madness.

I was fortunate to be raised by my grandmother and another aunt. In fact, my grandmother’s home, called ‘The Retreat’, was the hub of the activities for her large extended family. I was raised by the proverbial “village”. My father led such a busy and active literary life, he would be out of the house from early morning till late night, so I was forced to share him with the world, often feeling lonely, despite having loving aunts, uncles, cousins at my grandmother’s home. I would wait for his “Kavitam!” on the creaky, old staircase at exactly 11pm each night. We did, however, make several lunch appointments, visit the Jehangir Art Gallery together and I would attend most of his poetry readings, with my family. He was a delight to be with, a storyteller par excellence and had a wonderful sense of humour. Of course, the bonus came in the form of having him as a teacher at the University of Bombay when I was doing my master’s degree. When I taught morning college in my first job, he would insist on walking me to the bus stop at six-thirty in the morning, as I was overwhelmed by the construction workers that pushed and shoved their way into the bus. Wearing a saree for work was mandatory, and it added to my woes! I had been threatening to leave the job when he said, “nobody leaves a job for a saree”. I later wrote a short nonfiction piece with that title. The family situation was a challenging and traumatic time for me, and I have recently started expressing those experiences in my poetry. I have learned that in all circumstances, one does what one needs to, and the strength comes from faith in God, at least for me.

At the time of my birth, we lived at my grandmother’s house, but it was for a short while only. We then moved as her home was getting overcrowded. My father selected our first home, a ground floor rented flat, not simply because it was near the sea, which he loved, but because it had a garden, and I could play in it. My mother would tell me that, and many other stories about his bond with me, growing up. She would often say that he spoilt me and would never say “no” to me for anything. He was all for letting me have experiences, like going on the school trips to various parts of India, even though the cost strained the family budget. He would indulge my love of music by buying a Philip’s turntable record player, which cost a fortune in those days. “Don’t worry”, he would say, “the money will come”.

He stole time from his sleep to write, after an entire day’s teaching. When I wanted to go to boarding school at the age of nine, my mother was against the idea, but my father spoke his usual “let her have the experience”. Later, knowing that I was part of the St Xavier’s College choir that performed the Hallelujah Chorus at the inter-collegiate choir competition (and won the trophy) and loved Handel’s Messiah, he purchased the double album in Amsterdam, and carried it all the way, on the plane to Bombay. When he walked through the door with the white double album with the emblem of the gold cross on it, I asked why he did not put it in his suitcase. He said he was afraid it would break. On Saturday nights, there would be a quiz contest on the radio, with a question at the end, which I would answer. He would have a postcard-ready in his meticulous handwriting, with the address provided, and literally walk briskly to the post box at the far end of our street to post it. The prize would be an album from a popular band and I vividly remember winning an album of the group ‘The Mamas and the Papas’, whose songs I loved. I wanted to go with him, but he said, “you might slow the pace down and reduce your chances of winning the LP”. Only the first to answer the question correctly would get the prize.

My father never told me what to do or what not to do, his guidance was always gentle and positive, but this day was different. I was off to St Xavier’s College for my classes. I had worn a lace white blouse with three red rose motifs on the front. My father looked up from the newspaper he was reading and asked me to go and change the blouse and wear something more modest. He said, “That kind of clothing will alienate the common man”. I was surprised at his observation of the blouse, as I did not see anything wrong with it at the time, But I was respectful, and complied. Later, when I reflected on what he meant, it then became evident that travelling on a local bus, with people from different strata of society, would invite unwelcome stares and comments. (But I took the blouse in my bag and changed into it in the college washroom – since St. Xavier’s, in Bombay, was a very fashionable institution, and the blouse would be “all right”!!)

Urna: The former Israeli President, Shimon Peres, was an admirer of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and a supporter of India’s bid on the UN Security Council. What is more, his immense respect and love for Nissim Ezekiel’s poetry. Peres often quoted from Ezekiel’s poem Acceptance in his public lectures. Its opening lines, “I am alone/And you are alone. So why can’t we be/alone together” was seen by Peres as a metaphor for how Israelis and Palestinians could sit across the table and discuss their common problems. Tell us a little about this beautiful bond between Shimon Peres and Nissim Ezekiel?

Kavita: First let me say how grateful I am to my cousin, Nissim Ezekiel, (my father’s younger brother’s son) for sharing the story of my father’s connection with Shimon Peres. Without him, the story would never have been told.

The story behind the special connection between Shimon Peres and my father, is one of the highlights of my life, one that I will always treasure. My cousin, Nissim Ezekiel, (working at The World Bank at the time) and who shares a name with my father, had gone to Israel for a meeting in 2005, as part of a team to assist the Government of Israel and the Palestinian Authority, in creating conditions for economic development in Gaza following the Israeli withdrawal. The meeting was led by Prime Minister Sharon. When Shimon Peres entered the room and looked closely at the business cards of the delegates, he asked “Which one of you is Nissim Ezekiel, and are you related to the poet?” I quote the exact lines from my cousin’s speech made in Las Vegas at the Adelson Educational Campus, titled: ‘Honouring Shimon Peres’ Legacy.’ My cousin, who is an economist and a musician as well, replied that that the poet was his uncle, his father’s older brother. That is when Shimon Peres turned to him and said very simply, “You should know that your uncle is one of my favourite poets in the world, and when I need peace myself – I always turn to his poetry.” Then, my cousin narrated in his speech of how Mr. Peres went to his large cluttered work table (the resemblance to my father’s desk struck me) and retrieved an older version of my father’s poems. He then proceeded to tell the team that whenever he met with his Palestinian counterparts in his endless search for peaceful solutions, he always quoted the lines from my father’s poem ‘Acceptance’: “I am alone, you are alone, so why can’t we be alone together.’’ He used these lines in major public events, such as welcoming Jewish athletes from around the world to the Maccabiah Games in Israel.

When my cousin, Nissim, met Mr. Peres two months later he presented him with the latest version of my father’s poetry, which had been published after his death. Later, he received a ‘gracious’ note from Mr. Peres on his formal letterhead as Vice Prime Minister thanking him for the gift of my father’s poetry, acknowledging him as a remarkable poet and remembering his “WORDS OF WISDOM”.

Urna: Nissim Ezekiel was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1983 for his collection, ‘Latter-Day Psalms’, and the Padma Shree, five years later for his stellar, inimitable contribution to Indo-Anglian writing. Share with us an anecdote or two, about the family’s initial reactions and excitement, as and when the news started pouring in.

Kavita: Each year, we returned to Bombay for a two-month vacation from the International School in Mussoorie, (in North India), where we were working at the time. The residential school was closed for the winter months, and the students went home to their families. The Indian staff too went to their homes in different parts of India, and the foreign staff did some travelling, while others went to their homes overseas. Travelling by taxi down the winding roads from Mussoorie to Delhi, and then by the Rajdhani Express to Bombay with the children, was a much-anticipated event. From Bombay Central station we would go first to my mother’s house for a couple of days. Little did we know how special the year 1988 would be!

One morning the bell rang at five am. We were all fast asleep, exhausted from our long journey. My husband stumbled to the door, to find a postman standing at the door with a telegram addressed to my father. My mother was already awake, frying the onions for the curry, as was her usual ritual. I do not recall whether she had heard the doorbell or not. In any case, my husband signed the receipt for the telegram and my mother asked him to open it. Suddenly, I heard an excited yell, “Daddy has won the Padma Shri, Daddy has won the Padma Shri.” I rushed to the living room and snatched the telegram from my husband’s hands. All of this awoke my startled little children, who had no idea what the excitement was all about, and promptly returned to sleep. Later, the phone started ringing incessantly. My mother asked us to answer the telephone and said quite matter-of-factly, “The meals still need to be cooked, even if Daddy has won the Padma Shri,” she said. Friends and family kept calling all day long. We answered every phone call, completely unable to conceal our pure joy. I think Daddy only found out when I made a phone call to him at the PEN office. He remained blissfully unaware (as he mostly was of worldly happenings) of the commotion the news about him had caused.

Later that evening, Daddy came home after his day’s work. I started hugging him and crying. “What’s all the crying for”, he said in his characteristic calm manner. “It’s just an award.”

I don’t remember much about where I was the day, he won the Sahitya Academy award in 1983, but I do remember feeling an immense pride in hearing the news. My father was a simple man with very few needs, never cared for money, awards, fame or prestige. He was devoted to his work with single-mindedness and simplicity, especially to poetry and to promoting the cause of poetry. He was a true philanthropist. If ever there was someone who could be described as “unworldly”, it was him.

Urna: The archetype of a poet is his immense strength, suffering, and probably, a sense of guilt for the family. You are carrying Nissim Ezekiel’s legacy. What are the symbolic cues and pointers about your chosen name, ‘Kavita’? Was it destiny? Tell us how your father chose this evocative, “prophetic” name for you? Also, what does it mean to you and your poetry?

Kavita: Preserving the legacy of my father is near and dear to my heart. As I mentioned earlier, it is not only accompanied by an immense pride but also carries with it a great responsibility. A Beatles book of lyrics which he purchased for me on one of his trips to New York had the inscription “To Kavita, with faith in her potential”. It is taking me a lifetime to fulfill that potential, but I believe I have begun. On another occasion when he was overseas, he told me he had a photograph of me on his desk. The deeply personal words he spoke about what happened next are words I will cherish in the deepest part of my soul. He said that the photograph spoke to him and told him that I was the extension of his soul. The poems I write to pay tribute to him, and, when they get published people can learn and understand the loving father and wonderful poet that he was. Most of my poems have a mention of my father, either directly or indirectly. It happens naturally as the result of the deep bond we shared. I have said in previous conversations that whatever shapes my life, shapes my poetry, and my father was a strong influence on my life in the life lessons he taught me. Whether he meant my name to shape my destiny or destiny had a hand in bringing a prophecy to be, when I was born, there is certainly something uncannily powerful in the bond we shared.

Now to the question about my name. My father put a lot of thought into everything he did. I am glad he thought carefully about naming me. One’s name is linked to one’s identity. It is the first thing people ask when you are introduced to them. It can conjure up images in a person’s mind of your character, though that may change when they get to know you. My name must have been symbolic to my father, if not prophetic. I am asked this question about the meaning of my name many times, which growing up I sort of took for granted, while still knowing that it was chosen with care. Kavita means “poem” or “poetry” in Sanskrit. My grandfather spoke Sanskrit, but I do not think that had anything to do with it. In Indian culture, children are named with meaning. This is more so than in Western cultures. In Hindu culture, the priest, after consulting the horoscope, comes up with a sound. The uncle then names the baby starting with the letter that corresponds to that sound.

My father could have chosen a Jewish name for me, but he chose Kavita, which makes me think it was meant to be intentionally symbolic. My mother and my siblings call me “Kavi”, which means “poet”, but that is just a nickname. They had no way of knowing that I may someday be a poet. Shakespeare said, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.’’ I have often wondered if I had another name, would I have been a very different person?

My other siblings are also named with meaning, as I have named my children with meaning too.

In my opinion, there is some veracity in your statement about the archetype of a poet being his immense strength, suffering and probably a sense of guilt for the family. From my knowledge of reading and teaching poetry, I feel this largely applies to male poets, though I cannot provide the specific statistics. This is not to negate the fact that women writers possess strength, or that they suffer and carry the burden of guilt for the family. Perhaps women may tend to know more about how to achieve a balance between their passion for writing and their home life. Having said that, some women writers remain single out of choice, while others may end up divorced as the pull and tug of domestic life may overwhelm them. My father displayed immense strength in his resilience to challenging or adverse events. He always spoke of responding to tough circumstances by developing the right attitude to it. “Happiness is a choice”, he maintained. All his life, he struggled with balancing his work with giving time to his family. It was particularly hard on my mother, and us children too. He suffered from some of the choices he made as far as the family was concerned and we suffered a great deal with him too. All families have their issues, but when your father is a public figure, maintaining the privacy of the family life becomes an issue.

Urna: Tell us more about Nissim Ezekiel, the man and the poet. What would you say was his most interesting or memorable writing quirk? How much of your father is palpable in you?

Kavita: It was interesting to watch how my father “composed” a poem. I have described it in my poem ‘How Daddy Wrote his Poetry’. He would lie down on the bed with a handkerchief over his eyes. The handkerchief features in my poem ‘The Black Bicycle’. He had already lit a Menthol Cool cigarette and taken just a puff of it. The smoke from the cigarette would keep curling to the ceiling and die out. Then he would get up and write a few lines on a lined notepad, of which he had several on his cluttered desk. In the centre of the desk was his typewriter, on which he typed his writing with two fingers. After writing a few lines of poetry, he would go back to the large old-styled bed and cover his eyes with his handkerchief once again. Then back to the desk, which I have described in a Haibun called ‘The Poet’s Desk’. When he was done, he would call me into the room, read out the poem, and ask me how I liked what he had written. He spoke slowly and deliberately and enunciated each word. He recited poetry so beautifully, it put you in the exact mood that matched the theme of his poem. He accepted suggestions with that characteristic twinkle in his eyes, though it was not for me to know whether he made any changes based on my suggestions. After all, he was the Master poet!

So much of my father is palpable in me, tangible in a way that friends and family can recognize it. Whenever I did or said something to my mother, she remarked, “you really are Daddy’s daughter”. When I was having an injection, I cried out for my daddy. My mother complained she had all the pain in giving birth to me, and I only screamed out for my father! Now, when I do or say something, or sometimes even when I write a poem, my husband will say, “that sounds just like your father”, not just my colloquial use of language, but the spirit and the mood of things in which he would have expressed them. I have my distinctive style and am comfortable using my own voice. Some of the gifts my father bequeathed me are my appreciation and love of life, my passion for teaching, especially the love of the students in my classes, a love of literature, especially poetry, and my emphasis on the values of integrity, graciousness, and humility. Other important values he inculcated in me were a strong empathy with the suffering of others, compassion for the poor and the needy, and an attitude of living and let live. My father was the poet of the inner life, he said one must pay attention to the soul, and I have always given importance to this. My life is an expression of the things he poured into me.

Something else I inherited from him, is a complete lack of aptitude for numbers and figures. In other words, my math just does not add up and I have little financial acumen, much to the chagrin of my mother! My husband has reassured me that, despite the fact of being Jewish but not having their legendary business skills, everything I touch turns to gold. He says I have the Midas touch! I am certain that is an inheritance from my father. He gave away money to anyone who asked and sometimes even to those who did not. There was no calculation in his giving. All he saw was the need of the person in front of him. And he responded. His blessings have returned to me in full measure.

One of the disappointments of my life, and in my relationship with my father, was that he never once “helped” me with my poetry. He felt strongly that he might be accused of nepotism and so, while he spent countless hours mentoring other young poets and writers, he studiously avoided reviewing my work. While my mother did not agree with his stance, I respected his choice, but I keep wondering whether the trajectory of my development as a poet and writer might have been on another plane altogether, had he taken an active interest in my work. He did, however, tell others that he was proud of me, and that I too was a “poet”. He carried my first book to Israel and showed it to one of the organisers of the event he was speaking at. She later sent me a picture of the book he had given her.

***

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca recites her father, Nissim Ezekiel’s poem

***

Five Poems by Nissim Ezekiel

Poem #1:

Poet, Lover, Birdwatcher

To force the pace and never to be still Is not the way of those who study birds Or women. The best poets wait for words. The hunt is not an exercise of will But patient love relaxing on a hill To note the movement of a timid wing; Until the one who knows that she is loved No longer waits but risks surrendering - In this the poet finds his moral proved, Who never spoke before his spirit moved. The slow movement seems, somehow, to say much more. To watch the rarer birds, you have to go Along deserted lanes and where the rivers flow In silence near the source, or by a shore Remote and thorny like the heart's dark floor. And there the women slowly turn around, Not only flesh and bone but myths of light With darkness at the core, and sense is found By poets lost in crooked, restless flight, The deaf can hear, the blind recover sight.

Poem #2:

Night of the Scorpion

I remember the night my mother was stung by a scorpion. Ten hours of steady rain had driven him to crawl beneath a sack of rice. Parting with his poison - flash of diabolic tail in the dark room - he risked the rain again. The peasants came like swarms of flies and buzzed the name of God a hundred times to paralyse the Evil One. With candles and with lanterns throwing giant scorpion shadows on the mud-baked walls they searched for him: he was not found. They clicked their tongues. With every movement that the scorpion made his poison moved in Mother's blood, they said. May he sit still, they said May the sins of your previous birth be burned away tonight, they said. May your suffering decrease the misfortunes of your next birth, they said. May the sum of all evil balanced in this unreal world against the sum of good become diminished by your pain. May the poison purify your flesh of desire, and your spirit of ambition, they said, and they sat around on the floor with my mother in the centre, the peace of understanding on each face. More candles, more lanterns, more neighbours, more insects, and the endless rain. My mother twisted through and through, groaning on a mat. My father, sceptic, rationalist, trying every curse and blessing, powder, mixture, herb and hybrid. He even poured a little paraffin upon the bitten toe and put a match to it. I watched the flame feeding on my mother. I watched the holy man perform his rites to tame the poison with an incantation. After twenty hours it lost its sting. My mother only said Thank God the scorpion picked on me And spared my children.

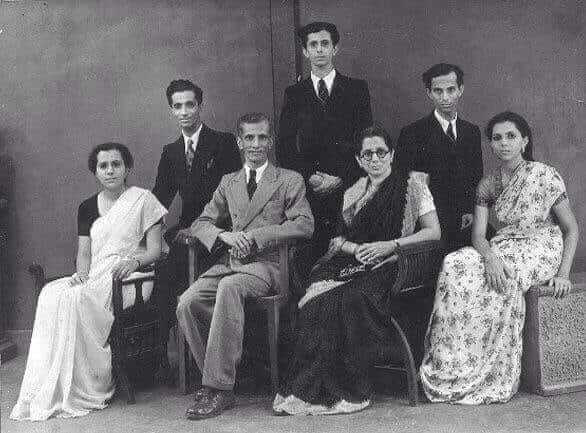

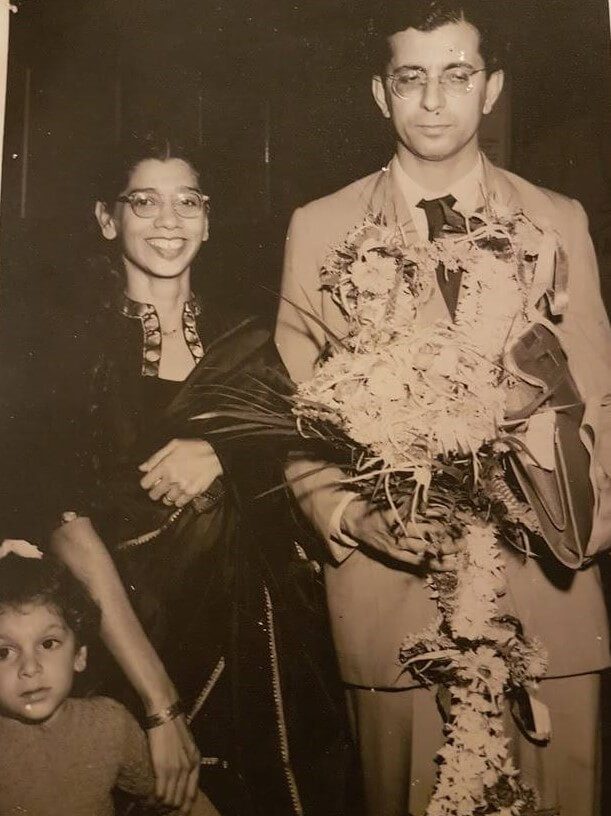

Nissim and his children

Nissim and his wife

Poem #3:

Mangoes

I have not come to Edinburgh. To remember Bombay mangoes, but I remember them. Even as I look at the monument to Sir Walter Scott, or stroll along In the Hermitage of Braid. Perhaps it is not the mangoes that my eyes and tongue long for, but Bombay as the fruit on which I’ve lived, winning and losing my little life.

Poem #4:

Squirrel

An agile flick of grey and brown And he is gone. Like a thought, To sport with leaves and sun, Indifferent to the bait. Fearing fingers of the watching child. But he must come, Fluent shape of him, to be caressed – As though he should be By definition of the mind – As to a home At any cost Bound.

Poem #5:

From Blessings

God grant you trees To live among, If not in reality Then in imagination, trees of such variety and beauty that you can’t help loving yourself among the trees.

Photos sourced from Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca and visual by Different Truths

Very well penned down , nicely written .

What a stupendous interview! Thanks Urna and team ! ❤️

Beautiful memories of a daughter dedicated to her father, the deep relation words can’t express. Loved every line revealing tiny bits and corners of life through a daughter’s lense.

Reading your interviews is an education in sensibility. Gratitude.

The interview brings out intimate details of both the poets — love, affection, respect, admiration. Stand benefited by reading it. Thanks for the pointed questions.