Reading Time: 6 minutes

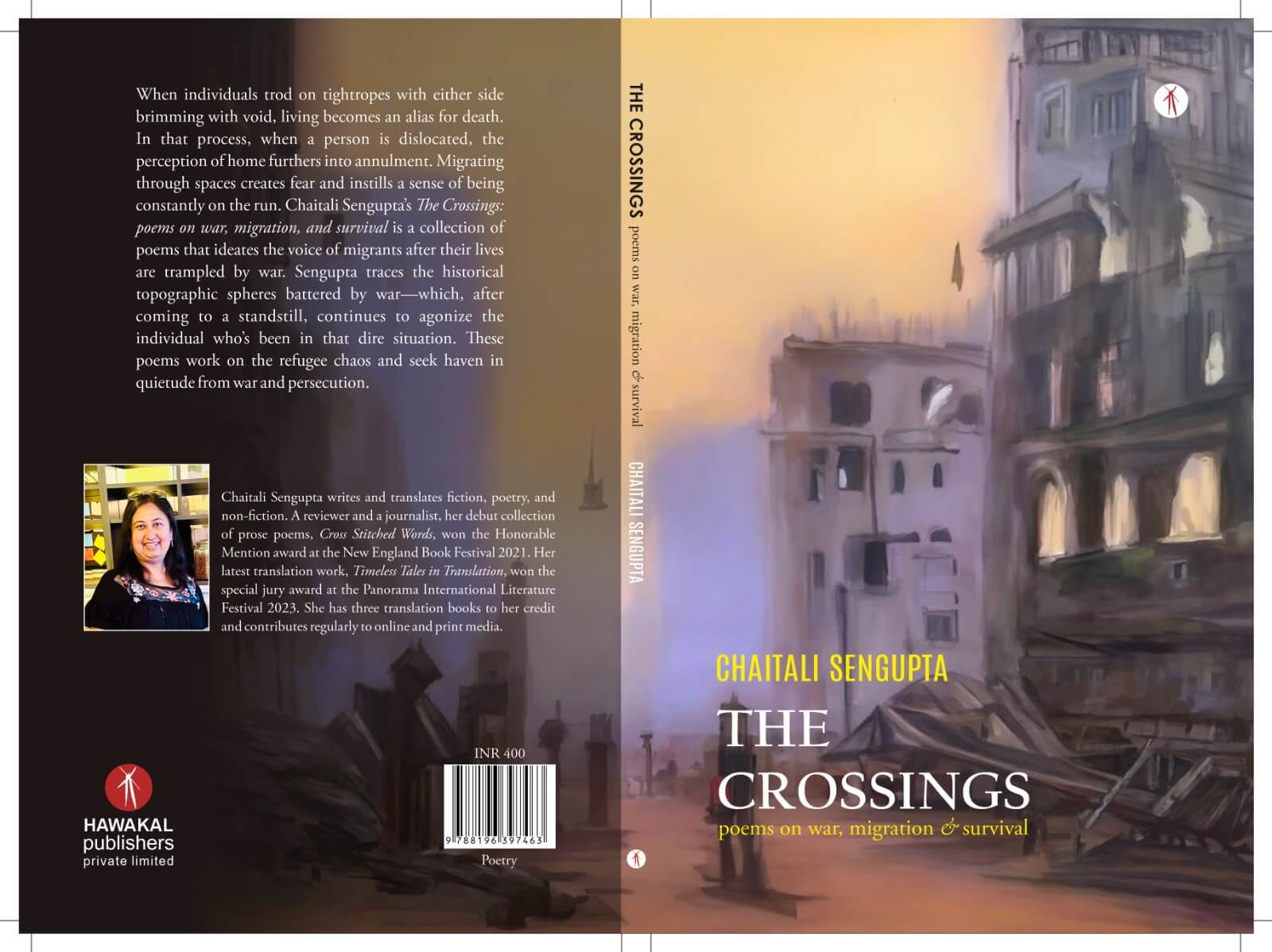

Navamalati reviews The Crossings, by Chaitali Sengupta, which explores the tragedy of war, highlighting the struggle for survival and respect amid immense hardships and the moral dilemma that persists even after the guns are silenced, exclusively for Different Truths.

The Crossings are a collection of Chaitali Sengupta’s deeply sensitive poems. The fifty poems sorted into three groups dwell beautifully on the reality of war and the problems that come up after wars end. Wars are not the thought of magical talisman that ends problems. They are the beginning with no end. This is the writer, translator, reviewer, and journalist Sengupta’s second poetry collection. With wars abounding in our twenty-first-century world, and men grossly bent on killing each other, one is reminded of Oscar Wilde’s saying, “To live is the rarest thing in the world.” Indeed, we have not moved away from our blood-soaked earth, where the bewildering battle of Kurukshetra was fought. And Sengupta in her very fifth poem Kurukshetra:

The Battlefield of Human Mind writes… O Arjuna, each war is a war of greed, alas! In our tottering earth, there is a Kurukshetra in every dotted matrix.

Where it is fought, war is a period of dark despondency and a moral dilemma for the people. It is a trick of incorrigible fate on a timeless civilisation. Where does the dignity of human life rest during a war? Just a look at the children of Gaza fills one’s heart with irrepressible anxiety at the brazen impunity of mankind.

The poems in The Crossings are all about despair and chaos. The faint faded light at the end of the tunnel is hardly sufficient for one to live. Being alive in a refugee camp is not about life! It breaks one’s heart when the poet writes about people like us scavenging for lost dignity.

The clothes whisper. The Threads weave absurd delusions of my once proud lineage, wrapped in cardigans and soft cashmere. Now, without that grey latex over-sized suit. I’m a pauper.

What happens in a war and after a war can never be ever forgotten. Can anyone forget the horror of the Iran/Iraq war? To have been able to reach beyond the barbed wires and get a chance to live and speak of life calls for a celebration! Living like prisoners in overcrowded slums makes one forget that once they lived in the jasmine-scented city in old Iraq. (I Have an Afterward). To be able to live in a camp in a gun-less world and walk on the indifferent streets (The Shelter), does indeed make one feel secure, but then one has lost one’s home, one’s city, one’s dear ones. One may not be buffeted by the storms of war, but has one not become a mere number?

I’m number 36754ON90 and I’ve a shelter now. There I wait like Time in amnesia.

And there the people from Kabul must learn how it feels to be without war. In Growing Roots, the new home in Afghanistan after escaping the horrors wrought in Kabul, is again an alien blister.

To this home, I try not To carry my yesterdays. I learn to cook pasta, talk to The tulips. I listen to the F M radio

How can such sorrows be negotiated? What consolation or assurances can be poured? Can one help but sit with indifference with one’s jowls sinking into one’s chest? Chaitali Sengupta’s poems in The Crossings are hard-hitting, and one realises that with such disorientation, one can never be whole again! The weight of living alone saps their energy.

Stubbornly individualistic in the grip of agonising wars, the pain of the migrants became a sore feeling as the poet says, ‘My mother died as a refugee.’ She will never know her agony, her pain, her passion. Grief becomes the hinge on which the poet’s memories of that time burst in a staccato refrain,

But Time has no legs to travel back, you see. She was willing to trade her all, just to have a glance… if the lamb in her courtyard, did give birth to an ewe.

Passion, emotion, and sentiments…all spent! It is difficult to reconnect and relive the fears that drove them from their homestead like a driven whip. In the poem The Language of the Immigrant, the migrant stands before The Statue of Liberty with a mind deeply hounded, knowing full well that he is not welcomed, but tolerated.

I think of the Cuban bread through the fog. It carried my mother’s smell, too. I think of the bare food shelves in my land. Of the soil of my village bottled in my rucksack.

In the poem, No More Scared, the migrant can never be lulled to an acceptance of such horrendous truths as a war brings about. They are not done with the memory of throwing soil on the scorched brows of dead sons and daughters; of their women overpowered and smelling of blood and shame. The smell of death had clung on and they tasted its sting on their African tongues. A war never ends when the battle is fought and done.

Chaitali Sengupta’s anthology The Crossings will remain in the minds of readers, for she has brought forward the feeling of wretchedness that spreads like a fungus on the minds and hearts of people who had known no war, and can not have any feeling of empathy towards those little children who have lost not only their homes and dear ones but also their country before they knew what a country was all about! It is all about cognitive psychology and behavioural disquiet. The poems grouped under Survival have a poem, To Find Another Home, where the similes are so painfully true and picturesque.

In the camp school, we sit hunched like lumps

in the watery oatmeal……

we are restless,

stoop-shouldered, hunching down. Like the wild ants.

We’re without mothers.

And we’re without homes. Both disintegrated.

I felt as though a war was a long breathless muffled sob!

The poet Sengupta painfully states how it stays on like a discarded fishbone in a puddle drummed down into oblivion. She is very correct in her affirmation that such children learn to pick up the rifle (Not Unwanted) for he was baptized by hate, with rage filling the core of their being. The question that looms here is, is it being fortunate to be merely alive? The blatant irony of the pain of the refugees that has seeped into their beings like rainwater is as true as it is palpable. This is the history of mankind all over the globe. Chaitali’s trenchant voice holds on to times past and times present. The certitude with which she has woven her poems touches our hearts with Ukraine, Hamas, and Gaza always on the newspaper headlines. War is the other name for death. Figuratively and literally, war is like an ugly sore that always spreads its putrid smell all around. The scars of loss of one’s dear ones and the mental and physical displacement, never really heal. Resilience does not feature there, for the hollow and empty feeling remains.

Through War, Migration and Survival, we find proud faces in the realm of history crack, patience flies, courage lost, privations drown hope, and cries of grief ram down one’s throat. Can we ever forget Bhisma’s bed of arrows, or Draupadi’s tears with her dead sons about her, or the dear sixteen-year-old Abhimanyu caught in the hands of Shakuni, Drona, Karn, Kripa, Asvathama and Kritavarma, all like bloodhounds! Chaitali speaks about the use of howitzers to stinger missiles in her poem Counting Wars,

War for me is the curve of my finger on the trigger. And the smell of gunpowder on my breath.

Like a defaced Bamiyan Buddha, on the streets of Lindengracht her thumb and finger rub the rosary as she learns to count wars on the beads. The Crossings show how man crosses the limits of barbarousness. Grit and gore have no blessedness. I recall Vikram Seth’s painful poem on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki way back in 1945, and choose to quote here from Wilfred Owen’s poem, Strange Meeting…

Then when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels I would go up and wash them from sweet wells, Even with truths that lie too deep for taint.

The crossover of man’s life as Chaitali Sengupta’s The Crossings records, highlights the larger cache of horrifying truth of the migrants, the innocent victims of war. Reading about them is not about wringing our hearts, it is about a deeper realization of what is to be done and not done, about blithe belligerence. The way every stone has a story to tell, every migrant from all over the world has their own story. Nothing should eclipse the concern of mankind. Thanks to Hawakal Publishers for the publication of The Crossings and the beautiful way it has been presented.

Cover photo sourced by the author