Reading Time: 5 minutes

In a world swayed by patriarchy, the body of a woman has been objectified in mythology, literature and in visual media, rues Pratima. An exclusive for Different Truths.

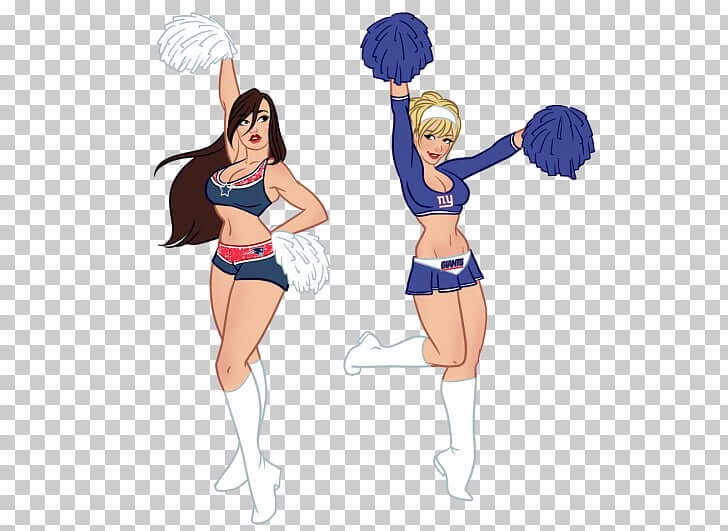

The ‘body’ of a woman has always been the subject of much controversy. Its perception tends to vacillate between the surging emotions of deep desirability and odious misogyny. In a world swayed by patriarchy, the body of a woman has been objectified in mythology, literature and in visual media. The presence of beautiful women on stage has always added to the much-needed tadka deployed to allure the audience to watch any godforsaken programme. It is perhaps for this reason that scantily clad women have been introduced as cheerleaders in cricket as well as in other sports.

The presence of beautiful women on stage has always added to the much-needed tadka deployed to allure the audience to watch any godforsaken programme. It is perhaps for this reason that scantily clad women have been introduced as cheerleaders in cricket as well as in other sports.

In one of our greatest Indian epics, the Mahabharata, the game of the politics of power between the Pandavas and the Kauravas was played on the body of Draupadi. Similarly, in the Ramayana, distorting the face of the rakshasi, Surpanakha and the abduction of Rama’s beautiful wife Sita gave rise to an immediate crisis and called for a ferocious battle between Rama and Ravana. The various shakti peethas (temples for the worship of goddesses) in our country emerged out of the divine strength in different parts of a woman’s body, that of the goddess Sati. The legend behind the shakti peethas is based on the story of the death of the goddess Sati. Out of grief and sorrow, Shiva carried Sati’s body, reminiscing about their moments as a couple, and roamed around the universe with it. Vishnu had cut her body into fifty-one body parts, using his Sudarshana Chakra, which fell on Earth to become sacred sites where all the people can pay homage to the Goddess.

Thus, body and woman seem to be so intricately woven that one cannot be thought of without reference to the other. All our belief systems also rest on the body of woman — whether it be torching her body for dowry, beating her up, slapping her, scratching her, punishing her body to bring her round, setting her body off on pyre as in the practice of Sati, murdering the girl child in female foeticide and infanticide, secluding her when her body menstruates, adoring her if her body is capable of giving birth to a male child and conversely despising her for giving birth to a girl child, or not giving birth at all, raping her if she crosses her limits, habitually passing scathing sexist remarks on her in schools/ colleges/ classrooms/ all public places, calling her unchaste and polluted if she has a broken hymen or if she has a sexual encounter before marriage, mutilating her genitals in parts of Africa, the Middle East and South East Asia to keep a check on her sexual desires, shaving off her hair and draping her with a white sari if her husband dies with no fault of hers — the women and body are inextricable. Even the experiences of growing up, menstruation, hormonal fluctuations, the painful and superhuman process of giving birth are all linked up with the female body.

The importance of the woman’s body was recognised by the French feminist critic, Helene Cixous. She writes about her idea of ecriture feminine. The French phrase implies that women should write from their bodies.

The importance of the woman’s body was recognised by the French feminist critic, Helene Cixous. She writes about her idea of ecriture feminine. The French phrase implies that women should write from their bodies. As Cixous says, “Women must write through their bodies, they must invent the impregnable language that will wreck partitions, classes, and rhetoric, regulations and codes, they must submerge, cut through, get beyond the ultimate reverse-discourse, including the one that laughs at the very idea of pronouncing the word ‘silence’…In one another we will never be lacking.” (Cixous, The Laugh of Medusa).

Cixous believes that the women should write through their bodies — the bodies of diseased, ailing, silent women suffering endlessly behind the veil since ages should come to the fore. She also mentions that women should write in ‘the white ink’; the white ink refers to a mother’s milk, which is specific to a woman and to her alone with no interference of patriarchy. As a woman writer, I have felt that oftentimes my pen knows no limits —sometimes my prose in later stages turns into poetry and oftentimes my poetry tends to be prosaic. While a man’s writing is essentially logical, coherent, clear and flows in one direction, writings by women often flow like a turbulent river in all directions. Perhaps a woman’s writing ought to be a semblance of her overburdened, disorganised existence under the garb of being organised. I often find myself cooking while penning down my thoughts, while the mischievous cooker whistles disrupting the flow of thoughts. This precarious existence, this multitasking can only be projected through an unstable writing form, which is and should not follow a linear path.

The famous French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan classifies three stages of the unconscious — the unworldly imaginary stage of incoherence in infancy, the mirror stage in childhood and the logical symbolic stage at maturity. Cixous sees the Imaginary stage as the soil for the burgeoning of a woman’s writing and the symbolic stage as an inspiration for a man’s writings.

The famous French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan classifies three stages of the unconscious — the unworldly imaginary stage of incoherence in infancy, the mirror stage in childhood and the logical symbolic stage at maturity. Cixous sees the Imaginary stage as the soil for the burgeoning of a woman’s writing and the symbolic stage as an inspiration for a man’s writings. Defying the patriarchal form of writing, defying the symbolic stage of logic and reason, a woman delves into the ocean of imaginary stage which breaks the logical, rational, compartmentalised writing of the symbolic realm of a man’s writing to produce a typically feminine work. It is for this reason that Cixous reinstates the importance of a woman’s body in writing and says that a woman should write from her body, the body of a woman in a patriarchal society, a body subjected to violence, to shame, to objectification and also to experiences of love and motherhood. A short poem exemplifying ecriture feminine flowed from my pen:

Her Soul

Do not shovel your hand beneath

for you will make love and go,

enjoy the delicacy and honeyed dew

of a woman’s body —

which will fill you with milk and love

from the day you were born to the day you die.

But have you delved within?

beyond the statuette and image

and waded deep into

deep into the intricate nerves of the woman’s brain,

deep into the making of her soul?

There, if you dare to venture

you will find obdurate mettle

made obdurate and strong

by centuries and centuries of decapitation.

The vociferous voices in the voiceless

will smother you

and you will be submerged in an ocean of tears,

pouring down heavily from Sita, Eve till Nirbhaya

with a continuous flow.

Photo from the Internet

Feature picture from UIhere.com

Amazing thoughts