Reading Time: 6 minutes

In this paper, Nachiketa attempts to hold an overview of the expression of women in sculpture (poetry in stone) up to the precolonial period from ancient India. Here is the first of the three parts, which explores the erotic (Maithuna) and folk elements in Indian art, exclusively for Different Truths.

Having religious intention, aiming metaphysical existence, Indian art may not be an adjunct of religion and metaphysics but belongs to the traditional arena of the ancient art form from which human moods and emotion emerge as abstract what oriental society says Rasa. Rasa is a noble mixture of moods, sentiment, emotion, desire remaining as a seed in the mass heart or folk mind. Indian artists are geniuses. Their art is imbibed with symbol abstract which not only express but also suggest as a poet. Indian sculptors and painters are equivalent to poets.

Indian Art in Aesthetics

Radhakamal Mukherjee (1965) interpreted Indian Art rooted in myth and legend, rejuvenated regularly suggesting inner vision and experience in comparison to European Art, which clarifies external phenomenon. The vision and practice of Indian artists are unearthly, mystic, and abstract. He explained citing Alankākra Rāghava and Chandralok of Jaydev, that a sense of aesthetic beauty is the noble quality of persons, who obtain impersonal delight tamed by the expression of Rasa and enduring sentiments are resulting out of the successive stage of bibhava. Rasa as a concept is as old as Natysastra. These are available and hold good for every fine art. Nine types of Nabarasa are love, humour, compassion, fury, valor, awesomeness, loathsomeness, and wonder as defined in Vishnu Dharmattara, Aparajita Prachya (3rd-4th Century), or 11 Rasas in Samaranga Sutradhara of painting. The central dogma of aesthetic beauty lies in Rasa whatever the categories, which transcends persons investing feelings of modified heart with serenity.

Rasa theorist highlights the sublimity, dominance of sattva, and kindness to the mystic experience of the highest order of Rasa-experience.

Whereas Bhatta Nayak (9th century) Rasa theorist expressed aesthetic experience – as the experience of the aesthetic object by subject in the state of perfect bliss (Ananda) when universal. Rasa theorist highlights the sublimity, dominance of sattva, and kindness to the mystic experience of the highest order of Rasa-experience.

That is why aesthetic enjoyment is considered akin to the supreme bliss of Brahman apprehension. Indian thought stresses the fruitful interchange between aesthetics and spiritual moods and apprehension. Indian primary attributes (Gunas) personality of purity (Sattva). Purity signifies universality, having expression of silence (Santa) compassion (Karuna) or dynamic creativity (Rajas) having an expression of love (Sringer), valour (Veera), laughter (Hassya). Third one is ignorance or inertia (Tamas) denotes wonder (Advuta), fury (Roudra), grotesqueness (Vivatsya), awesomeness (Vayankar).

Erotic Essence of Indian Art

The art of Ajanta was inspired by early Buddhist Bhiksuk during ruler Ashok (273-36 BC) by Dharrmarakshita along with architectural activity in the Deccan establishing monasteries. According to ancient texts that is why a series of monasteries were carved out along the Sahyadri [Sangharam, Chaitagriha, Vihar]. Ajanta excavation was probably introduced, while patronised by Satavahana kings when Hinayana was flourished.

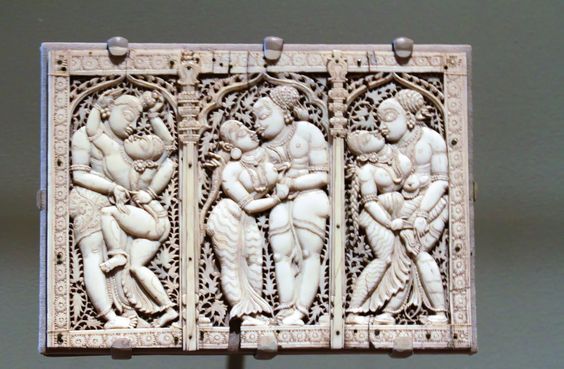

An increasingly prevalent motif in temple iconography from the first century AD was the erotic or loving couple known as the Maithuna image.

An increasingly prevalent motif in temple iconography from the first century AD was the erotic or loving couple known as the Maithuna image. These appeared on monuments such as the Sanci Stupa and the door frames of Deogarh, they also appeared at Ajanta, Ellora, Karle, Aurangabad, Konark (Bhubaneswar), Mukhalingam, Sirpur, Lalitgiri, Udaygiri, Baijantha. Maithuna couples were most found on thresholds and weak architectural juncture. This, together with evidence of ancient texts, supports the suggestion that they fulfilled a magico-protective function and were memorisation of ancient non-Vedic fertility rituals. The Silpasastras, Purans, and other authoritative texts implicitly recognised the auspicious (mangala) and protective defensive (raksartham-varanartha) aspects of erotic depictions.

Elgood (2000) opined citing the interpretation of Agni Purana and Brihat Samhita, which suggest that doors of the temple sanctum sanctorum (garbhagriha), should be protected by Maithuna imagery, which allows erotic images on seared temples while discouraging their appearance on the walls of domestic house.

Some folk cult induced non-Brahmic unorthodox imagery are considered, which were placed by dominating culture and sponsorship of the aristocracy and patronage.

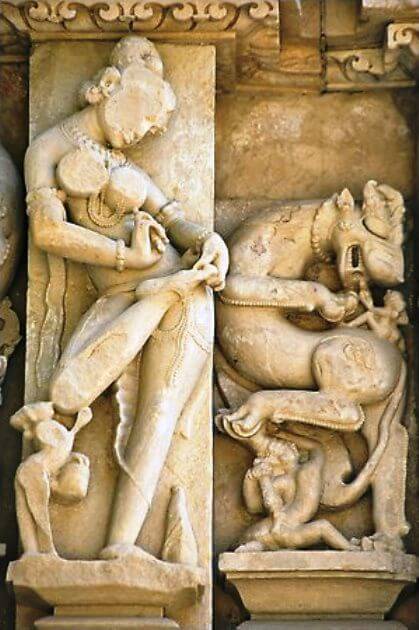

Some folk cult induced non-Brahmic unorthodox imagery are considered, which were placed by dominating culture and sponsorship of the aristocracy and patronage. During 900-950 AD, there was a profession of a more consistent, blatant, and sophisticated treatment of sexual depiction of the Maithuna couple represented in sculptural decorations of the temples of the western Deccan (Mahanut, Aihole, Badami cave, Pattadakal, Ellora) and so on. Even on the Jain parsavanatha temple of Khajuraho, and the Buddhist temple No 45 at Sanchi, Hindu temples belonging to the Saiva, Vaishnava and Sakta sects, Maithuna images were prevalent. Regional displaying of Maithuna with varied treatment initiated in short, in some (Sun and Madhor) Hindu temples. Erotic figures on the plinth, shaft of pilers, lintels and laksanas in a crude manner were conventional. Carving of bold and prominent Maithuna images as seen in Konark and Khajuraho from the 10th century is considered as acceptance of the form. It was a representation of a fully realised aesthetic concept in contrast to archaic.

Mother Goddess Cult

Mother Goddess cult stating whether such sculptures represent the sexual taste of that era or feminine aesthetic or feminine representation at the religious level is relevant for knowing the development of female divinities. Pieces of evidence are revealed from Harappa civilisation, Vedic period, Puranic text, Mauryan period, Gupta period. Female divinity recorded in stone was noted by Rajpal and Prakash (2014), while studying Kailash temple, Ellora through aesthetic artistic impression discussed on icons like Gajalakshmi panel [Lakshmi, the Goddess of fortune and wealth], Ganga and Yamuna, the River Goddesses [Fertility Goddess, physical and spiritual purifier], Saraswati [water deity, Goddess of speech and creative arts], which are stand curved with large hips, narrow waist heavy breast and elongated limbs against the background of flowers. Mahishasura Mardini Durga [dynamic force of Prakrit (nature) as the destroyer of evil] seated on lion pose in a fight with Mahisasur equipped with bow and other weapons [trident, sword, shield, etc.] Rati [the Goddess of sensuousness] holding sugar cane [Rasa – the essence of life] and her beauty is reflecting sensuality in the Abhanga pose, whereas Uma/Parvati [Goddess of knowledge] seated in Ardhaprayanka pose, somewhere in a cross-legged posture, resting on lotuses and her right hand holding left arm of Shiva, or in Trivanga pose in Gangadhar-Shiva panel. The Kalyanasundara Murti panel exhibits the marriage of Shiva and Parvati carved according to Vithipa tradition.

Saptamatrika [seven Mother-Goddesses] worship is as old as Harappan culture, which ultimately matured in the Puranik period…

Saptamatrika [seven Mother-Goddesses] worship is as old as Harappan culture, which ultimately matured in the Puranik period, also mentioned in the literature of Bhasa, Shudrak, and Banbhatta. Saptamatrika iare Shaivate goddess, designated as – Brahmi (holding rosary and water pot), Maheswhari (seated on a bull, holding a trident, wearing serpent bracelet, crescent moon), Kumari [rides peacock, holds spear], Vaishnavi [seated on Garuda] holds a conch, wheel, mace, bow, sword], Varahi [boar-form], Narsimhi [lioness-women], Aindri [holding thunderbolt] consisting of six Devashakti and one Devishakti. Nagini, female attendant, Bhudevi (Earth Goddess), Nidhis are others. But wonderful sculpture of stone as poetry, beautiful movements, seducing posture, or flying celestial.

Stella Kramrisch, in her monumental works on The Hindu Temple Vol- II inked, “India thinks in images; the image (Murti) itself is beheld as a divinity, Murti, the wife of Dharma (The order of things in the cosmos and righteousness in mass), is form, luminous and charming, without her, the Supreme spirit (Paramatman), whose abode is the whole universe, would be without support.” Her charm and attractions are those of the anima mundi, cosmic vitality, active in the middle region (Antariksa), in space. There the temple has its extension (Bramhavaivarta Puran).

Loklila and Fertility Symbol

Maithuna figure depicts male and female aspect of fertility engaged in worldly sport [Loklila] although amorous couple are used in ornamentation and auspiciousness. According to Rajpal and Prakash (2014), Ellora expression establish that artisan carvers are not only simply artist but also ingrained into the reams of Bhakti and canonical injunction.

So far women in love are in centrality in Indian literature than man’s love for women. Possibly women were empowered and honored in the then Indian society.

The female body is beautiful from the males’ eyes. So, the belief was beauty in women. So far women in love are in centrality in Indian literature than man’s love for women. Possibly women were empowered and honored in the then Indian society. “A glance at the thousands of ancient temples of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism will reveal numerous attractive statues of young, uncovered women, but rarely do we ever find nude statues of men. Many of those statues are of Goddesses, though statues are also found of Apsaras, Yakshinis, Naginis, and other such creatures, who so to say occupy a position midway between humans and divinities,” recorded Cyril Veliath cited by Rajpal and Prakash (2014). Commoner India worshipped Mother Goddess from time immemorial in various forms in the cultural history as his/her own mother as revealed from text line Debi Mahatmya. Even the Tree Goddess depicted in Shalbhanjika sculptor represents the auspicious power of the bounties of nature in an idealised Indian female form. Salabhanjika is named after Sal tree (sorea robusta), a symbol of Hindu God and bhanjka means beautiful women found in Hindu Jain and Buddhist art. Tree-goddess may not be divinity but is associated with fertility symbol. In one Hoysala Temple Salbhanjka Goddess stands under leafy bush ornamented in Tribhanga pose of Indian dance.

Stella Kramrisch, in her monumental works on The Hindu Temple Vol-II further recorded, “Maithuna as a symbol of Moksha, ultimate release, means a union, like that of the fire and its burning power, which is inseparable from, and in the fire from the beginning. Maithuna as practiced and be held by the Sadhana is a reunion, for in the beginning the Purusa, the essence, was “like a man and woman in close embrace. It desired a second, Himself the Purusa divided into two, so were born man and wife. He united himself to her. [Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4. 1-4].

(To be continued)

Pictures from the internet.