Reading Time: 7 minutes

Dr Roopali walks down memory lane and tells us of an arduous journey on a bicycle from Lahore to Delhi, along with its joys – exclusively for Different Truths.

This is a long-ago story of travel and adventure. It is my father’s story of traversing the vast subcontinent of India. It is a graphic story told and retold as we grew up in a much-travelled military family.

Its excitement and amazement remain etched in my mind. Yet as the years go by, many facts and figures of that eventful journey turn sepia coloured. Before they fade away, I must recount the travel tale of a young man and his bicycle from Lahore to Delhi.

It is a promise I had made. “I think you should write it down,” I often told him. “You do it. I will dictate,” he would always say.

My father’s family had travelled from Dhaka in East Bengal to Lahore in West Punjab.

My father’s family had travelled from Dhaka in East Bengal to Lahore in West Punjab. It was the early 1930s. They moved from one end of the country to another, lock, stock and barrel, full of memories.

They left behind their once peaceful lives in a sprawling mansion with fish pukur (ponds), coconut palms, mango groves and jackfruit trees. Later, when the country was divided, our grandfather’s house was occupied and converted into a Pakistan Army officers’ mess.

Dhaka is where the Sircars, a well-known, highly educated aristocratic family, had lived. A palpable sadness stayed in their lives. My father and his siblings talked a great deal about it whenever they chanced to get together.

We never asked why they had moved. They never mentioned it, either.

We never asked why they had moved. They never mentioned it, either. That all travels and movements are not happy was beyond the little child’s comprehension. That child was me.

What made them leave the salubrious environment where music and poetry blossomed in the backyard? Boats carried the sweet rossogolla in earthen pots and moved about door to door like in Venetian canals.

And those memories of snow-white rice and mustard immersed Ilish (Hilsa) fish and Koi carp. I have never known. Except I often heard my father sigh, “we are refugees from East and West Pakistan.” His voice was heavy with the feeling of homelessness.

These words percolated through my mind into my heart. Later, in the 1960s, The Beatles sang “Nowhere Man” and touched my heart.

Punjab, with its mustard fields, five rivers and progressive culture, may have drawn my paternal family there.

Punjab, with its mustard fields, five rivers and progressive culture, may have drawn my paternal family there. Or had they escaped simmering violence? I wasn’t to know. They were educated people and readily found their vocations.

There was a university job available, and my learned scholar older uncle, Jethamoshai, was appointed Head of the Sanskrit Department at Punjab University. My father sought admission to the English Department at the prestigious DAV College in Lahore. Academics and Professors came from Oxford and Cambridge to teach here.

He learnt French and began a French-language tutoring business to pay for college expenses. We were regaled with stories of graduate life. One often heard about the Anarkali gardens where father sat with his master’s degree books, trying to read.

Father, a veritable storyteller, kept our young minds constantly engaged.

Father, a veritable storyteller, kept our young minds constantly engaged. His superb literature notes began to come in handy as we, too, studied Shakespeare and Donne. It was the 1930s. Lahore was a cultural hub. An elegant and attractive style of living seemed to exist among students. Impeccably dressed young men sat in lecture halls. The beatnik student with scruffy hair was yet unknown.

And then it was the sweltering month of June. North India reeled under the blazing hot sun. Everything and everybody moved indoors. The wealthy travelled to the wondrous cool of the hills. So did the colonial daftar (official administrative staff). The rest of the world managed with the laboured whirring of ceiling fans.

Summer holidays would soon begin. A young man named Narendra Kumar Sircar had just finished his first year of M.A. exams. An English literature student, he had plenty of hanging about time and was restless to get away.

A two-storied houseful of female relatives with hungry fussy Bengali husbands was a nest of unfair culinary demands. If he didn’t get away, he would turn into an all-day random errand boy for his demanding relatives.

His exams could have gone off better. The reason was the beautiful movie star, Devika Rani.

His exams could have gone off better. The reason was the beautiful movie star, Devika Rani. His thoughts wouldn’t allow him to concentrate. He had been writing letters to her, hoping to get into films and act with her.

It was possible she would fall madly in love with him. He was handsome, after all. Shakespeare’s sonnets came in handy. Devika Rani patiently responded to his long letters. He explained that it was his time to study and build a career.

Soon the idea of poor grades and their older brother’s professorial admonishing voice compelled young Sircar to flee. He would get on a bicycle and pedal his way – more than five hundred kilometres to Delhi.

A satchel with a change of clothes, a cycle pump in case of a flat tyre, and just a few precious annas in his pocket! (An anna was a currency unit formerly used in British India. It was equal to 1⁄16th of a rupee).

The adventurous young man took to the highway with very little preparation.

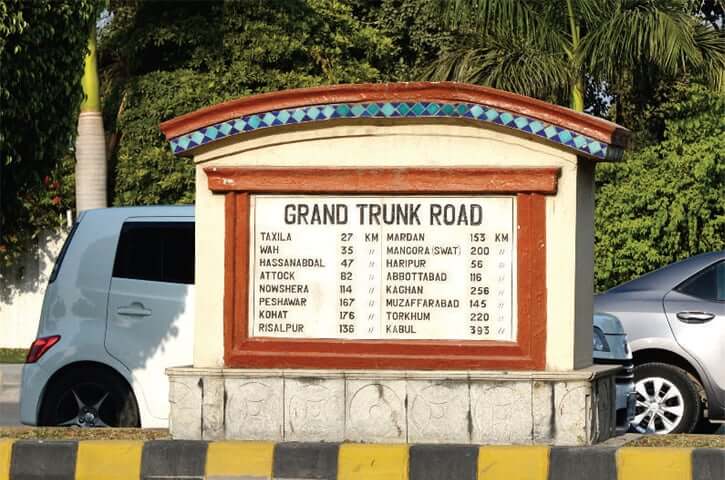

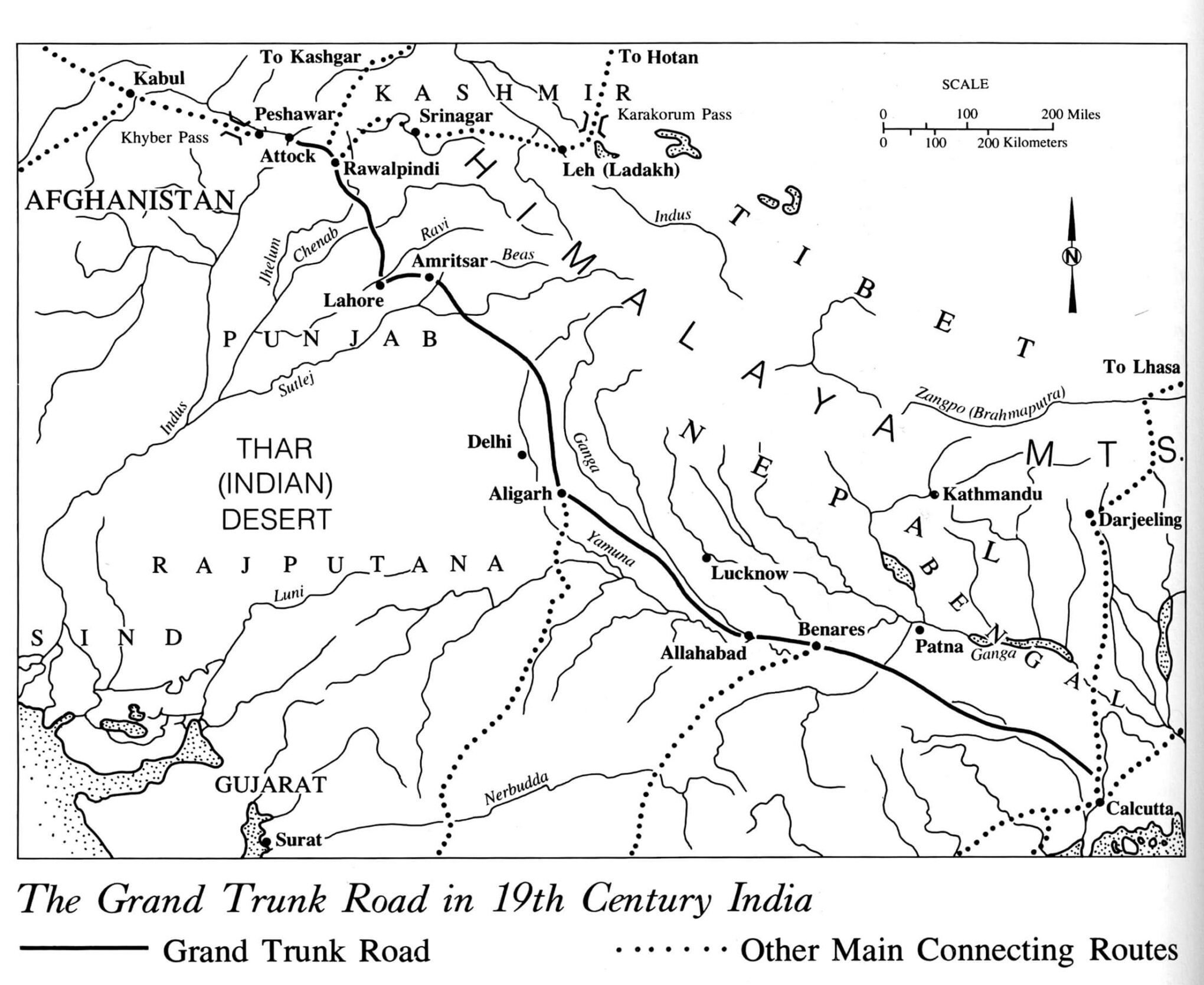

The adventurous young man took to the highway with very little preparation. And without informing his family. Off he went on the Grand Trunk (GT) Road. One of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads.

The road, often called the “Gernaili Sadak” (the Generals’ Road) and Sadak-e-Azam, covers 2,700 kilometres, running through parts of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

A fascinating highway, extending from Kabul through Lahore and Delhi and reaching Kolkata in West Bengal and Chittagong in Bangladesh. This busy asphalted road still forms a vital link for trade and communication.

I learned that the Grand Trunk Road existed during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya but was later built by Sher Shah Suri, a ruler of the Indian sub-continent, in the 16th century. The road continues to Pakistan near Peshawar through the famous Khyber Pass.

This famous international mountain pass, at an elevation of 1,070 meters, is one of the oldest known passes in the world and connects Afghanistan and Pakistan. Beyond this mountain pass, the Grand Trunk Road goes down to Lahore and crosses into India at Wagha, and after 2,500 kilometres, the road ends in Kolkata.

Nowadays, the road is still the busiest and wildest in areas that are now part of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.

The journey, we were told, was an unforgettable experience.

The journey, we were told, was an unforgettable experience.

A few hours of cycling in the bristling heat brought the young man to a few roadside tea stalls. A cup of sweetened milky tea and two oily fried matri (snacks) later, he sat under a spreading Peepal tree.

He wiped the sweat dripping down his neck with the hanky tucked in his pocket. Some parts of the road were dirt tracks. Highway bandits were known to accost travellers. The brass cycle pump was his only weapon.

At midnight he arrived at Sabzi Mandi railway station in Purani (Old) Delhi. A well-lit platform offered a temporary safe resting place. An exhausted body teeming with a gnawing hunger and a parched throat was willing to fall asleep anywhere. The young traveller looked around for shelter and food.

A sleepy police constable directed him to an ashram where he might find shelter for a night or two.

A sleepy police constable directed him to an ashram where he might find shelter for a night or two. The ashram wasn’t far from the railway station. It sounded like heaven. He was offered a bed, but it was too late for a meal.

He managed a small clay tumbler of the cool (yoghurt) lassi drink from a roadside vendor. He lay down to sleep with almost the last penny in his pocket.

His body ached. The large ashram hall had rafters where pigeons fluttered all night. They generously showered gold and silver excreta. He never forgot and never forgave the pigeons. This is one part of the story I remember with utmost clarity. It was an extraordinary trauma.

With barely a coin or two in his pocket, he searched for a family known to his older brother. This family lived in Delhi. He had heard of them.

They had two kids. A boy and a girl were studying for their matriculation exams.

They had two kids. A boy and a girl were studying for their matriculation exams. They shopped for school textbooks and stationery from the well-known Janta Book Depot in Gole Market. This was a circular indoor market with shops selling various goods, including fish and chicken. The year was 1939.

Built in 1921 by Edward Lutyens, Gole Market is one of New Delhi’s oldest surviving colonial markets and is considered an architecturally significant structure.

He found the family! They lived nearby on Lodhi Road. Lahore to Delhi on a bicycle? An excited family welcomed the young adventurer. They were meeting for the first time.

It was a surprising and hearty welcome. After a warm bath and a sumptuous meal, he confessed he had left home in Lahore without informing a soul. An anxious host managed to send a message to Lahore by pulling strings at his office. The young traveller enjoyed their hospitality for a month and returned the favour by tutoring the two school kids.

While searching the Interwebs, trying to map my father’s bicycle wheels from Lahore to Delhi in 1939, I chanced upon a very interesting-looking book on the extended construction/paving of the Grand Trunk Road. It was written by a British, entitled, The Grand Trunk Road in the Punjab: 1849-1886, a K. M. Sarkar, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 1927 wrote it. The coincidence did not escape me.

Many a time and on many a train over many years, my train always stopped at a nondescript railway station called Subzi Mandi.

Many a time and on many a train over many years, my train always stopped at a nondescript railway station called Subzi Mandi. A station a stop away from New Delhi. An essential stop for the vegetables and grains moving from one part of India to the other.

My memories tumble forth each time: the pigeons, the clay tumbler of sweet lassi and my father’s story. I had been to Sabzi Mandi many times in my father’s stories.

Subzi Mandi is hallowed ground for me.

Lahore seems so far away.

Photos as by the author

Display Picture: The Grand Trunk Road in 19th Century India -Picture Courtesy Princeton University

I came across your story while searching the internet to plan a trip down the GTR from Lahore to Delhi. As a child growing up in Africa I read Rudyard Kipling’s Kim. A book that would be frowned upon today with its tales of the Raj. I was enthralled by the story of the travels on the Grand Trunk road. The book is probably what led to my love of different cultures and a desire to experience them. Your fathers story resonates with me as I have also lost my country and with it part of my soul. Like your father but at a much later stage in life I jumped on a bicycle in Sri Lanka and cycled around the lower part of the island via Anurhadapura . The part about stopping on the side of the road for tea and snacks in my case vada brings back fond memories. Thank you for the lovely story.