Reading Time: 9 minutes

Education changed the worldview of the protagonist, Dariya. She is at war with traditions and taboos in this story by Meher. Does she succeed? – an exclusive for Different Truths.

Bright red lipstick was Dariya’s defiance against being forced to cover up under the hated hijab. She would leave home in the black garment to keep peace with her father, but once she was away from their neighbourhood, the hijab would come off, exposing her face and stylish clothes. Today, though she was moving away from their village, she would take no such risk.

Unlike her father, she was educated, with a master’s degree in ancient Islamic art. Her father’s elder brother, who had worked with an American company during the occupation, had insisted that Ashkan should let her study. She spent four years in Kabul at his home till she graduated. But once the Americans abandoned Afghanistan, her father ordered her to return to AbBand.

Dariya wanted to stay in Kabul and join the protests against the new government. Ashkan would have none, maintaining that girls should not protest, let authorities do their job, and stay out of trouble. This time her uncle did not support her. He couldn’t take responsibility for her safety in turbulent times.

Dariya should have made more effort to fit into village life. Her mind had expanded.

Dariya should have made more effort to fit into village life. Her mind had expanded. Impossible to shrink it back. Under the pretext of cooking classes, she began organising secret meetings of women, encouraging them to read books and discuss contemporary events. She was going to skip today’s meeting.

She took a deep breath and emerged from her room to find her mother, looking frail and anxious, reclining against bolsters on the large square floor mattress; her impulse was to run up, hug her, and snuggle into her ample bosom as she had as a little girl. She held back. This was no time for sentiment. She had to be strong. Forcing herself to smile, she lowered herself beside her mother.

Sultana took her daughter’s hand, looking up wanly. “Are you sure we should be doing this?” she asked in a strained voice.

“One hundred percent sure.”

“I-I’ve never gone against your father …. He wants me to wait….” her mother’s voice was tremulous.

“We are not wasting any more time.”

Taking her mother’s arm, Dariya helped her get up.

Taking her mother’s arm, Dariya helped her get up. Both women ran a comb through long black hair, dabbed drops of the cologne on earlobes, wrists, and handkerchiefs, and then slipped into black from head to toe. Her father’s hookah stood cold on the side. No one had fed it fresh coal after yesterday’s argument. Arguments between father and daughter were frequent, but Dariya was determined not to be cowed down this time.

Gently but firmly, Dariya led her mother out of the house into the blazing sunlight. The dusty street had a few one-storied houses on one side, with grey sand stretching to the base of a mountain on the other. A solitary cyclist ambled past, green leaves hanging from the straw basket slung over the handlebar. The highway was half a kilometer away.

The morning sun was not yet hot. Sultana clutched her daughter’s hand for support. She strolled, her eyes fixed on the road to avoid tripping over stones. As a stray dog with matted fur trotted past, Dariya pulled her mother to the side. She had to protect herself from germs.

Sultana’s left arm was beginning to throb again.

Sultana’s left arm was beginning to throb again. Below the hijab, her right arm was folded into her left shoulder. The lump in her breast had started as a red patch which she initially ignored. When it began to harden, she showed it to her daughter. Dariya took her to their family physician, who recommended an MRI, but the village hospital did not have an MRI machine.

The nearest MRI centre was at Ghazni, three hours away. They would have to take Ashkan’s permission. Sultana kept putting it off. Finally, when fluid started oozing from Sultana’s breast, Dariya panicked and took her to Dr Rashida again. This time the doctor extracted a vial of liquid and sent it for a biopsy. The report – a malignant tumour. No more keeping secrets from Ashkan. And the start of a mini-war at home.

“I have to take Maman to Aliabad hospital at Ghazni,” said Dariya after telling her father the diagnosis.

“Dr Rashida has treated our family for years. Why go to another doctor?”

“Cancer is not an ordinary illness Dado. Dr Rashida is not qualified to treat cancer. She said we need a specialist.”

“Is there a woman doctor at that hospital?”

“There are very few women doctors in our country. No one I know has specialised in oncology! We have to take treatment where it’s available.”

“Wait a few days. I will find a woman doctor at another hospital.”

News of his wife’s cancer hit Ashkan hard.

News of his wife’s cancer hit Ashkan hard. He was a traditional Muslim doing namaaz five times daily, making his family keep all the Rozas. It was an unwritten law that a woman doctor treated women of the family. Ashkan recoiled at the thought of his wife unrobing before a man, exposing her breast to him.

Precious days he was passed as he made frantic enquiries for a female oncologist. His supplication to the Almighty became louder, more intense. But he would not see the reason. Puffing on his hookah, he kept muttering prayers as Dariya tried to convince him to be practical.

“Hundreds of people die of cancer. Maman must get proper treatment fast,” she pleaded.

“The day of one’s death is written in Holy Books. No one can challenge death.”

“The science of medicine is to extend life. Reduce suffering.”

“People suffer and die even after going to doctors.”

“Do you want mother to suffer and die?”

“Sultana is my wife. No man can touch her breast. I will decide who treats her.”

“She is my mother. I must save her life. Give up your old beliefs Dado! The world is changing.”

“Becoming worse day by day! Daughters don’t respect fathers. I should never have sent you to college.”

“If girls don’t go to college, how will there be women doctors?”

Her logic was lost on him. He could not consent to another man examining his wife’s breast. In desperation, Dariya decided to take Sultana to Ghazni without his consent. To keep hunting for a woman oncologist was a waste of time.

Sultana was in a quandary. She had been a traditional wife, following her husband’s wishes. But the pain was increasing, and the fluid was oozing. She was only fifty-seven. Scared of pain, scared of death. Her daughter was offering relief. Her daughter was educated. She trusted her.

The next day they waited till Ashkan had gone to the masjid.

The next day they waited till Ashkan had gone to the masjid. He would be gone for at least an hour. Enough time for Dariya and Sultana to get away. It would be risky to travel without a male escort. But there was no choice. The two women were covered head to toe in black. Not a time for Dariya to assert independence. For Sultana, it was uncharacteristic defiance. They travelled without an escort to see a male doctor against her husband’s wishes.

The highway snaked across the valley, a thin white ribbon gleaming in the morning sunlight. Two large trucks chugged towards each other in opposite directions. No other vehicles were visible. Dariya and Sultana stood at the edge of the road waiting for the bus that should have been there minutes ago. Motorbikes sped past, then a car without a number plate.

At last, a bus trundled up, overcrowded as usual. Dariya helped Sultana climb in. Only one seat was vacant at the back of the bus. Dariya had to stand till the next village, where three burly men got off.

It was a bumpy ride on a rough road pot-holed with grenade blasts over the years. Sultana winced in pain as the seat bounced with each bump. The throbbing in her breast became acute. She shut her eyes, missing the sight of the elaborate tomb of Mahmud of Ghazni, a powerful ruler who had built an empire in the tenth century.

Dariya could barely suppress her excitement as the rotund towers of Ghazni’s citadel came into view.

Dariya could barely suppress her excitement as the rotund towers of Ghazni’s citadel came into view. She had frequented the Rawza Museum of Islamic Art in the walled city while researching her thesis on the twelfth-century Ghazni panel. The exquisite white marble with interwoven vines and arabesques from the palace of Sultan Masud had been stolen from the Rawza Museum. After several years, it landed in a European auction, selling for $50,000.

Her eyes misted as she recalled her father’s rare approval when she told her parents that after lengthy negotiations, the Ghazni panel had been returned to Afghanistan by Hamburg’s Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbe. It was the only time he saw value in his daughter’s education as he told the village how his daughter’s work helped bring back a valuable part of Afghanistan’s history.

Before entering the city, the bus detoured around three of Ghazni citadel’s thirty-two towers, half of which had collapsed. A camel stood munching leaves of a palm tree in front of a dusty tea stall where half a dozen men were chatting on charpoys. A fragrance of ginger and cinnamon wafted in. They drove past a wall draped with drying animal skins, past a mausoleum, and into a crowded bazaar street. Aliabad hospital, with its imposing pillars, was just ahead.

Sultana’s apprehension surfaced as they entered the hospital. “Will I …. have to take off …. everything?” she asked anxiously.

“It’s done professionally, Mamani. Don’t worry,” replied Dariya leading her mother to a comfortable chair while she showed the file to a woman behind the reception counter. Though a scarf covered her hair, the woman’s face was open. Another woman bent over a broom sweeping the floor was covered in black despite the hijab approaching her work.

A nurse beckoned Sultana into a small cubicle-like room, where she handed her a surgical gown. Again, Sultana asked, “Do I…. need to…take off everything?”

The nurse seemed used to the question. “I will cover you up. The doctor will only see what he needs to see. Wear this gown and press the bell.”

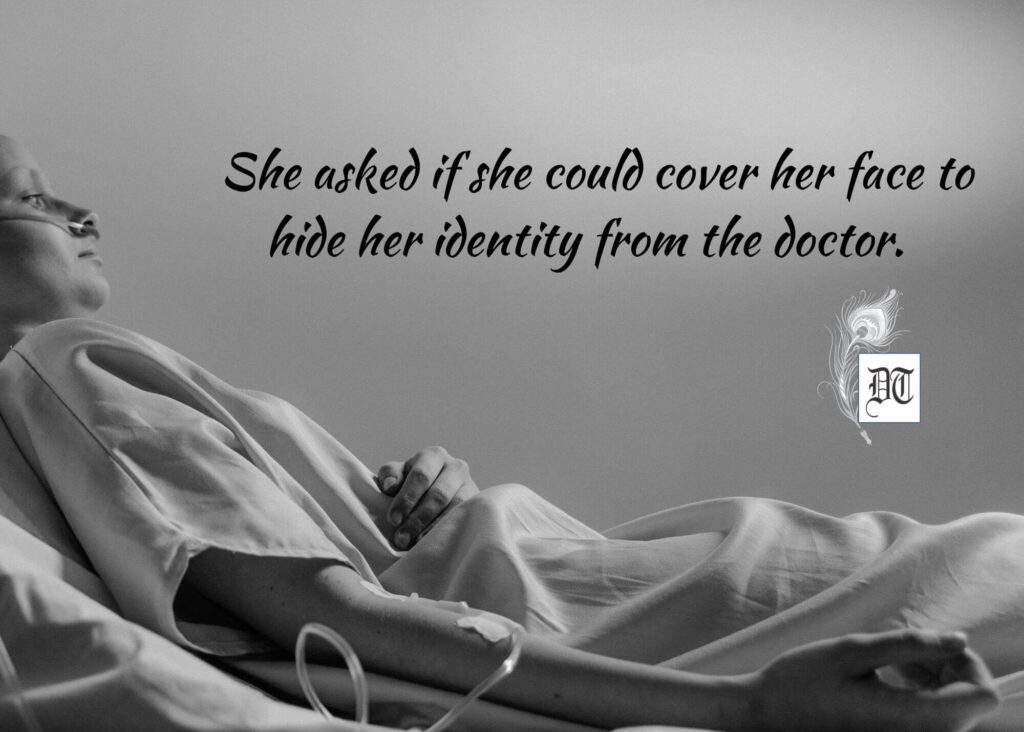

Sultana slipped into the green hospital gown and lay on the narrow bed, breathing tensely …

Sultana slipped into the green hospital gown and lay on the narrow bed, breathing tensely, wondering what was to follow. She asked if she could cover her face to hide her identity from the doctor. But the nurse had gone.

With her mother finally in the care of professionals, Dariya’s anxiety formed words in her head. How far had cancer spread? Could it be arrested? How painful would it get? Would her mother survive? She hoped they hadn’t reached for treatment too late.

The nurse returned and opened the strings of the gown. She strategically covered Sultana with a white sheet, leaving a square slit open. As she checked the temperature, blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen levels, Sultana kept asking, “what will the doctor do? Will it hurt? How long will it take? We have to catch the bus at 3 o’clock.” Finally, the nurse managed to get away. Dariya could hear her briefing the doctor in the adjoining room.

Dr Khan, a grey-haired man with thick glasses and a pointed French beard, entered with a smile and placed his stethoscope on Sultana’s forehead. “You are worrying too much. Your brain is getting hot,” he said playfully, patting her cheek. He kept chatting amiably as he went through her file and biopsy reports. By the time he started examining the lump in her breast, she had relaxed. His face turned grim.

Dariya needed an eye for the spectacular sunset tinting snow gold on the mountaintops.

Dariya needed an eye for the spectacular sunset tinting snow gold on the mountaintops. Her mind was fixed on how to break the news to her father. He would be furious that they had gone to Ghazni without his permission. Winning his support was vital. Maman would never agree to treatment without his consent.

Ashkan was puffing on his hookah as they entered. Bloodshot eyes glared at the mother-daughter duo. “What did the doctor say?” he barked. “I am not a fool. I know you went to Ghazni. Women are travelling alone! Did no one arrest you?”

Dariya had done her homework. “The Mahram rule says women must be escorted if they travel more than seventy-eight kilometers. Ghazni is much less than that.”

Ashkan seemed to have not heard her. “So, what did the doctor say?” he barked again.

Dariya. She decided to give it to him straight. “Cancer has reached stage two. She needs Mastectomy”.

“Meaning?”

“Her breast has to be removed.”

“Will she survive?”

“If it’s done soon. She will need radiation after surgery to prevent cancer from recurring.”

“Doctor was old, like my father,” intervened Sultana, hoping to pacify him.

“Even your father waited outside when you were feeding our babies!” he thundered, clearing his throat and aiming at the spittoon.

“We have to get Maman proper treatment fast, Dado. This is a life and death situation.”

“Let the village know that another man handled my wife’s breast! All the women in our village go to Dr Rashida.”

Dariya could no longer hold it all in. “They don’t have cancer!” she shouted. “Cancer is a killer!”

“Cancer, cancer, cancer…! Everyone has to die one day….”

“What are you saying, father!”

“Get out of the room! Leave me alone with my wife!”

Dariya looked from her mother to her father and back again.

Dariya looked from her mother to her father and back again. Her mother nodded hesitantly. Reluctantly she left her parents alone, knowing Sultana would be outmaneuvered. “Shut the door!” yelled her father.

She stood outside, her ear pressed against the door, trying to make sense of their murmurings. Ashkan was speaking belligerently between fits of coughing. Sultana was weeping. Their words could have been more explicit except for her name, which repeatedly cropped up. Finally, she was called in.

“I’m sending you back to Kabul tomorrow. My brother is expecting you. The university is shut, but you can stay with him.”

Dariya couldn’t believe her ears. “What are you saying!”

“You always wanted to go back to Kabul. So, go. I’m not stopping you any longer.”

“What about Maman?”

“She is my wife. I will take care of her.”

Picture design by Anumita Roy

Such a powerful story of a personal generational clash. Clinging to old cultural ethics even in the face of suffering, illness, and death. The story interrogates all who push love aside in favor of deprived skewed cultural norms, however diverse. Patriarchy shows it’s ugly face in entrapping this father to the point of being complicit in the illness, suffering and death of his wife and shunning his own daughter. It is often love of others that gives us the courage to break through false norms and morays. Those who lack courage and curiosity in a world becoming conscious are fodder for cults and fundamentalist. This story, beautifully told with rich descriptions speaks to all of us about the vital need to measure, yes, but participate in positive cultural change.