Reading Time: 5 minutes

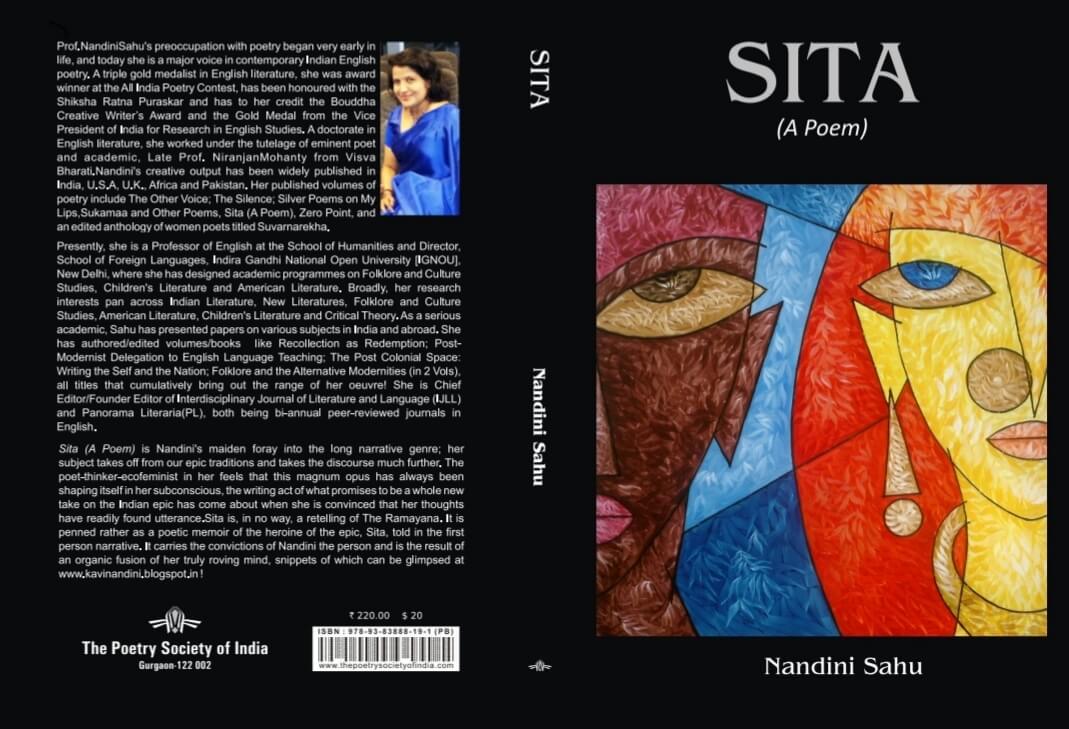

Dr Tapan reviews Prof Nandini Sahu’s long poem, Sita, stating, “She (Sita) is an outcast, ‘the exile of Rama,’ who creates ‘the realisation of the ethics of banishment'” – exclusively for Different Truths.

The subject of Sita, a prominent character of Hindu mythology, has engaged many minds over the millennia. The epic poem, Ramayana, has been read and re-read and dramatised in its different versions, in other languages, in different cultural and geographical locations in India and abroad. Like the text itself, its central female protagonist is polyphonic in character, whose complexity has been drawn attention to by literary critics who have often read her story from the margins of the grand narrative of the triumph of good over evil emblematised by the overpowering of the ‘demon’ Ravan through the agency of the virtuous Ram, the King of Ayodhya and ‘Maryada Purushottam.’

In a recent article published in the November 2021 issue of The Caravan, Saswati Sengupta highlights the irony of Ram’s consolidation of his righteousness at the end of his journey back from exile to his kingdom through the banishment of a supposedly violated Sita. Sengupta cites the much-quoted cry of torment from Sita at her public humiliation by her husband.

"What sin did I commit previously, Or whom did I separate from his wife, That I – a virtuous wife of blameless conduct – Has the lord of the earth abandoned you?"

The multi-dimensional persona of Sita has also been invoked in a collection of essays edited by Malashri Lal and Namita Gokhale ( New Delhi: Yatra Books and Penguin Books, 2009 ) in which reputed scholars of the ilk of Meghnad Desai and Reba Som and Nabaneeta Dev Sen have debated and discussed the “intensely human” traits of Sita, her “vulnerabilities” which, as Namita Gokhale has put it, “are lost in accretions of myth and reverence.”

Nandini Sahu’s long poem, Sita, is a valuable addition to the literature generated around the figure of Sita…

Nandini Sahu’s long poem, Sita, is a valuable addition to the literature generated around the figure of Sita; it is Sita’s “poetic memoir” couched in the form of a “first-person narrative.” Written in epic mode, Sahu’s work is a re-arrangement of the six ‘kandas’ or books in Valmiki’s Ramayana into twenty-five cantos or sections.

It is premised upon the idea of the ordinariness of Sita. “There is a bit of Sitaness in every woman.” Sita can be read, according to Sahu, who is a professor of both Folklore Studies and also of Literature in English at the Indira Gandhi National Open University ( IGNOU ) in New Delhi, as a most powerful woman like Goddess Kali or as a marginalised tribal or rural woman, a subaltern entity, or even a modern-day progressive or empowered woman who is likely to see a bit of herself in the self-willed, stubborn, confident, mortal woman, Sita.

Sita, the poem, in Sahu’s words, is about “the contemporaneity of Sita.” “Could I say I have deconstructed the stereotypical ‘Sita’ and instituted the bits and pieces of the bold and beautiful Sita in all of us?”

The invocation itself is in the third person – bringing forth and celebrating … the multiple identities of Sita.

The poem, which comprises twenty-five shorter poems, each made up of several three-lined stanzas, begins, like all epics, with an invocation. The invocation itself is in the third person – bringing forth and celebrating, in the poet’s voice, the multiple identities of Sita.

The initial description of Sita in the invocation is of a piece with traditional, derivative discourse.

"… she is Woman, She is every woman, the propagated, interpolated role model. The woman who adopted a self-imposed exile: The woman whom time and again patriarchy finds safe to evict in her emancipated consciousness."

But very soon, the canon is prised open, and indeed, disfigured too, as the narrative brushes and rushes past the familiar and familial icon of female perfection, Sita – Sati, the doted-upon daughter of King Janak and the devoted consort of King Ram, past the orthodoxies of Kalidasa’s Raghuvansha and Bhavabhuti’s Uttara Ramayana, to dwell upon the heterodox ‘heroine’ of the “Uttara Kanda”, the oft-ignored final portion of the Ramayana.

In this portion, Sita is no longer Ramaa, the queen and queen’s mother. She is an outcast, “the exile of Rama,” who creates “the realisation of the ethics of banishment.” But more than that, she is a single parent who

"– valiantly bears and rears her sons, Lava- Kusha. They are Sita-putra' as christened by Valmiki, not Rama-putra".

It is from this alternative vantage point, says Sahu, that she has plotted her poem.

"Can you do justice to the anguish of a mother, loyal, elemental, integral to her children's lives without approving the the fate of Sita? Can you comprehend the story of many a dedicated parent, the tales of single parents, re-telling the tale of Sita Hence this poem –"

In the poem, as Sahu conceives it, Sita is neither a docile nor a dormant victim.

In the poem, as Sahu conceives it, Sita is neither a docile nor a dormant victim. In the context of her difficult circumstances, she speaks up and speaks back. “– she has never been reticent. Never given up.”

This is the justification for a poem written in the autobiographical genre. The voice of this sufferer cannot be stifled. She is but one of a kind. The female protagonists of classical epics do not usually articulate their thoughts, that is if they have any thoughts. But Sahu’s epic is an epic with a difference.

Is there a principle of unity which holds this epic poem together? Here again, Sahu diverges from the classical epic formulation. In her story of Sita, there is no beginning, middle, or end. Its beginning is at the end of the master/’s epic:

"I designate my torment and wield my sovereignty By retiring from Rama after he asks me to Take a second test of fire, but I have completed The full cycle of my professed duties of daughterhood, wifehood and motherhood. Beyond patriarchal manipulations and domestic blues."

After all, Sahu’s Sita herself is a disruptive character.

It would not be an exaggeration to remark that there is a disruptive intention in reversing the narrative order. After all, Sahu’s Sita herself is a disruptive character. A vital aspect of the disruptiveness of Sita in the text is the premium which she puts on the importance of companionship between women in a man’s world. “I am entwined in many a woman of substance.” Apart from her three sisters, Urmila, Mandavi and Srutakriti, each one married to a brother of Ram, respectively, she has sororal relationships with other women of repute such as Anasuya, Gargi, Maitreyi, Ahalaya, Mandodari and Tara. But the women whose lives she claims to share and, therefore, embody stretch beyond times ancient to times modern, to the present-day – the Florence Nightingales, the Hellen Kellers, the Mother Teresas and the Malalas. Intertextuality is an outstanding feature of Sahu’s epic: she borrows her reference points for delineating Sita’s multifaceted predicament from within the national, the international, and even the cosmic frameworks.

The implied audience of Sita’s lines is always Ram. But her tone of address to him is not of veneration, not even of love. Instead, it is sharply interrogative, often undisguisedly a tone of reproof.

"Oh Rama! My esteemed husband for lives! I may be your ultimate love and dedication, But you rescued your pride, not me, from Ravana; thus, Sita may be your muse eternal. But think twice, you'll get the 'loyalty' of the real Sita the day you no more demand her to be 'loyal.'

Sahu might as well have given her poem another title: Ram demythified.

Book Cover sourced by the reviewer.