Reading Time: 11 minutes

Adil Jussawalla, an Indian poet with a complex background and a distinctive voice, defies categorisation and is instrumental in moulding the poetry of an entire generation. He reveals unknown facets of himself, his poetry, and his childhood in a no-holds-barred candid interview with Urna, exclusively for Different Truths.

Boxes are meant for things and collectables. Not for people, and certainly not for poets. Perhaps that’s why when I try to slot Adil Jussawalla’s work into neat, clearly demarcated silos and narrow, self-restrictive, gilded-cage definitions, I become increasingly aware of the futility of the task at hand.

How can I even attempt to pin down the historical, geographical, sociological, ethnographical, and psychological import of Jusswalla’s ironic, many-layered, evocative body of work? The sweeping expanse, or for that matter, the latitudes and longitudes of the aesthetics of Jussawalla’s poetry.

Not surprisingly, then, Adil Jussawalla has, continues to, and will always play a pivotal role in the birth of an entire generation of Indian poets writing in English.

Urna: Please tell us, your readers and fans, about some of the earliest influences in your life. People, authors, poets, schools, colleges, and having to navigate different languages and tongues. I’m keen to understand how much you would contribute to multilingualism if we were to deduce its foundational impact on your poetic voice when you look back.

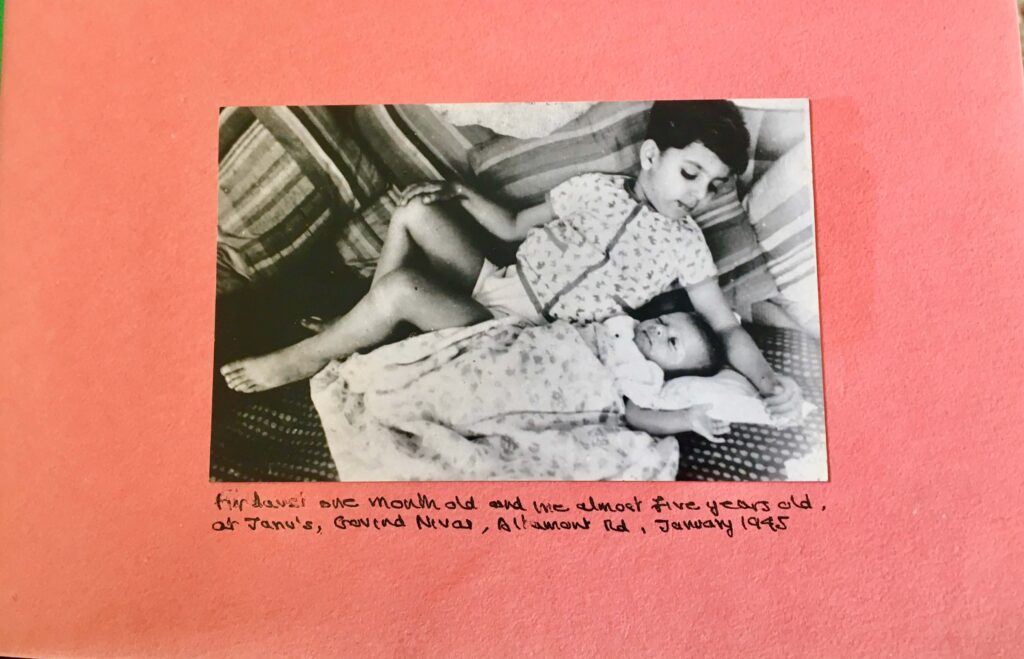

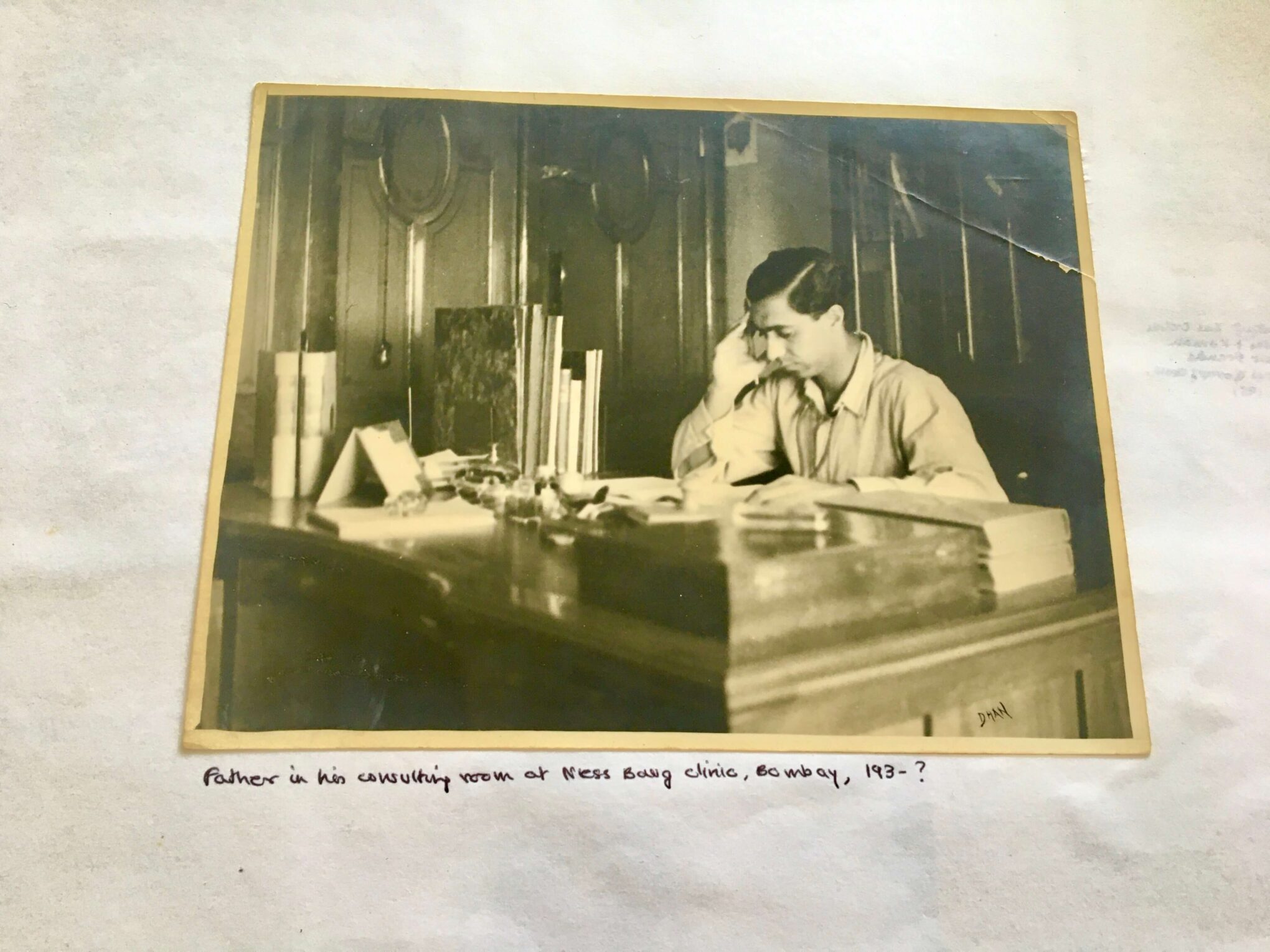

Adil: My younger brother Firdausi and I didn’t really have a home that was separate from my father’s workplace. He had a clinic with many rooms on the third floor of Sunama House on Cumballa Hill Road, now August Kranti Marg, opposite Shalimar Hotel. When I was born in 1940, my father was already beginning to establish himself as a naturopath, so he was professionally already an ‘outsider’ to the medical profession. The allopath regarded naturopathy as the practice of quacks with no scientific basis. In due time, apart from his practice and my father’s inner motivation to answer the allopaths — to say this is a rational and scientific form of treatment—he wrote a lot more books than I have written.

Now, I’m thinking, as I’m trying to map the somewhat ‘outsider’ quality of my parents because they both arrived in Bombay from elsewhere. In my father’s case, he came from a broken family in the North of India at that time. His mother left her husband and her four sons to settle in Pune. And my mother’s large family was in Jalna during her time, in Nizam’s state of Hyderabad, though it’s now in Maharashtra.

So, are you able to see my mixed influences from both of them, Urna? But what they had in common was the idea of being ‘modern’ and my mother had an artistic eye, which meant furnishing at least the family part of the clinic. We had just two rooms, and were furnished with what was regarded as modern furniture in the 1930s—both functional and less fussy. And to explain my mother’s artistic side to her, I must also mention that she spent more than a year in Shantiniketan from 1933 to 1934.

This is my family background, though my parents did separate from time to time. Perhaps that’s where I developed a poor sense of home, except as something interior with my colours and my dreams.

That home didn’t exist as a place for me, it was something more internal, if you like. It’s only now…now, after more than 50 years of living with my wife and my wife’s family, that I understand ‘home’. There’s the problem of carrying my baggage from my first family to this family, and I’m only trying to face that and come to terms with it now. I don’t think I’ll come to a closure or a somewhat deeper understanding of what home means, and what my family history did to me and my brother. And I end by saying, “Sitting under a tree in the rain, I thought of friendship and family, though it’s only occasionally that I understand those words.” I wrote this in 1998 (For Gentleman Magazine).

In school, I found that the teachers encouraged my writing, and in the art classes, my paintings were my solace. In fact, that was more than solace, as I wasn’t very good at games or sports.

In the beginning, no, I don’t think I was aware of my exposure to other languages in India before I went to England. I did make some grammatical and syntactical mistakes in Land’s End, which I’ve corrected subsequently.

After four years in England, I decided I’d had enough of that country, and I tried to continue my education in India. I had already given up architecture in England, and now I was giving up English literature (in Oxford) to continue with English Literature in India. But the colleges here wanted me to start more or less from scratch, they wanted me to take my inter-arts exams before I could try and get a degree, and that would have meant one more year would have gone by.

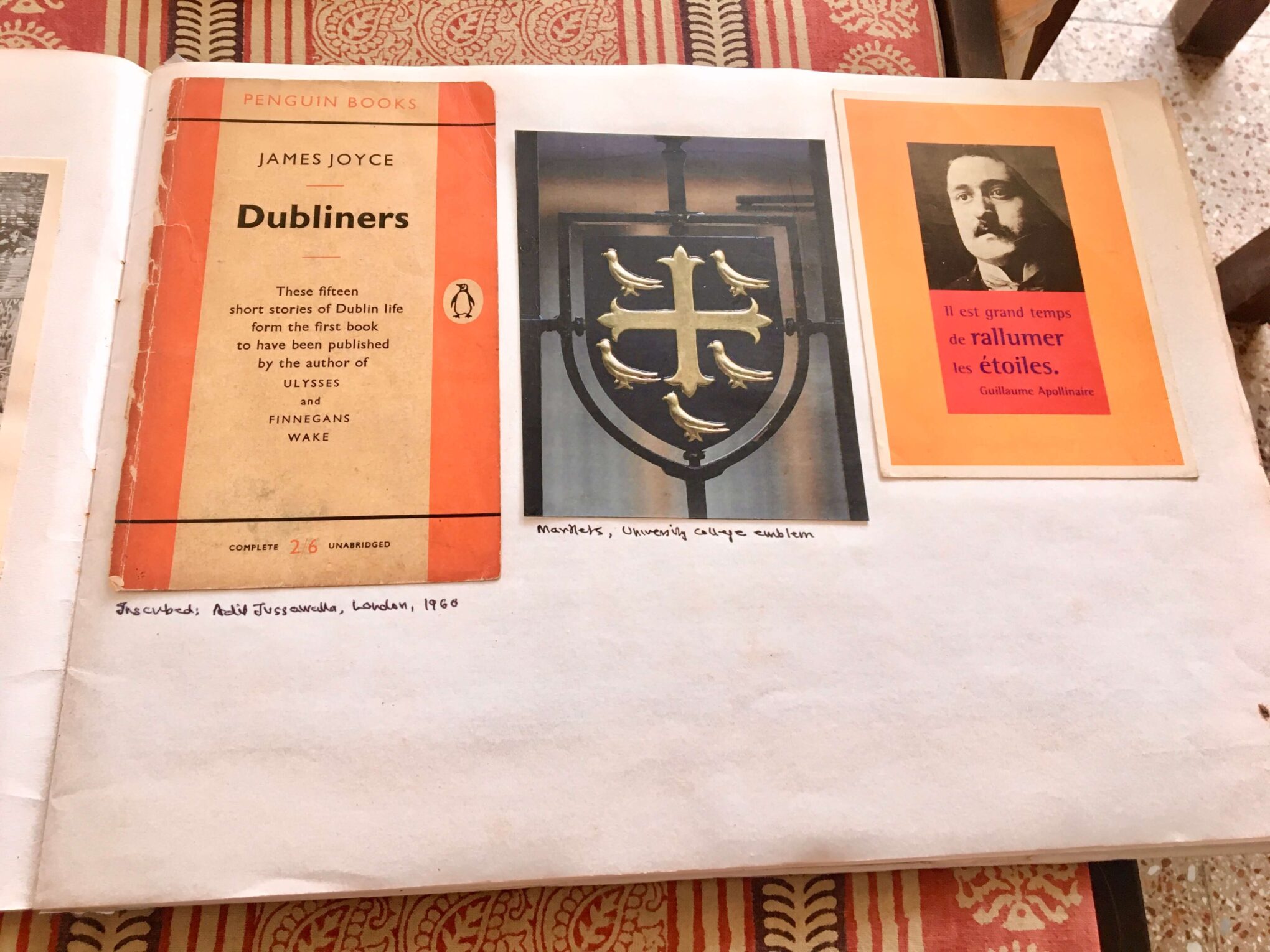

So, I asked my college in Oxford whether they would take me back, and they did. I literally crawled back, but to answer your question…yes, while I was in India, I became consciously more aware of the other languages, and I tried to use Hindi and Devanagari in my poems when I was writing.

I was not over-influenced by the Beats, but they helped me see another way of writing. Not just the formal, metrical poetry that I enjoyed writing, and I wish I could use more of that because I love using rhythm and sound in my work. Yes, I became aware of how important languages were to me, and that helped me select literature from this country for Penguin UK (New Writing in India), which largely contains writing from the languages, and it’ll be 50 years next year since it was published.

Urna: Could you please reflect a bit on living in England and France, before telling us what Mumbai means to you? You describe it as a “Castaway City”, and you’ve often said Mumbai does not provide you with a sense of ‘home’. How do you perceive your relationship with this metropolis in the context that so much of your poetry is deeply intertwined with its quintessence?

Adil: Well, let’s begin the answer like this. I found myself physically uncomfortable in England…I don’t think it’s the usual discontent with lodging and hints of racism or downright racism; it’s not so much that. I just felt physically crammed there…and I think this has to do with how I now see a lot of the sky and the sea.

Not only was the light in England somewhat dismal, but just seeing through gaps between buildings made me feel the constant need to be out in the open. I didn’t have much time for Oxford’s supposedly glorious architecture…I just wanted to be out…in places like Port Meadow. In contrast, Paris, and France in general, had much light. I only got to know Europe through hitchhiking. Never mind how awful the youth hostels could be. I just found the light somehow more energising. And this has been echoed by British writers themselves who feel physically happier on the continent or even further away, like Robert Graves in Majorca and Lawrence Durrell in different parts of Europe like Cyprus.

When I finally decided I had to return to Bombay despite my job as a teacher in London, I just instinctively felt more writing could come from me if I were based in India. Except that, I found that I’m not, despite what I said in an interview that I’m an urban poet, I don’t think I am… I’m not happy living in big cities. I like the anonymity of a big city, but much of Bombay as a city is hard to live in. I feel more connected with natural things, objects, and so on.

My position now is that of someone who may not understand exactly what home is, but I’m happy that I have shelter. I see, rather perversely, I suppose, that all of us live in shelters, not homes. None of what we call our homes is permanent.

Urna: As a child, colours and painting fascinated you, and you took to drawing and painting. So, when and how did you start seeing yourself as a writer? Our readers would love it if you could share that iconic story about Rider Salmon and your introduction to modern poetry.

Adil: There was no real shift, as I indicated in an earlier answer… my mother especially encouraged me to paint, draw, and use colours, and friends of the family gave me a diary when I was about 15 or so. I used it to put down my thoughts on different things, but I found it as I did in my essays in school… I was concerned with form—how I began things and how I ended things. So, I suppose the writer in me was already there, though I had no ambitions to be a professional writer. The school had a magazine called The Borderer, and I did submit a story to it…not set in India, but somewhere in Europe in the savage north—and I did write satirical verse for The Borderer. So clearly, I just didn’t write for myself…I wanted the writing to be seen by others.

Then, in 1955, when I completed my Senior Cambridge exam, school ended at standard nine, and I was ready to move out and go to college like my other classmates. But in that crucial year, the school introduced a two-year course called the HSC, and that meant I could get what they called A levels in England, which would qualify me to go to England if I wanted to join a college there.

You couldn’t enter a college in England unless you had two or three A-level subjects. So, I don’t know… I think the principal was keen that I should take this course, and I found myself with just a small batch of students, but the school had imported a Welsh teacher by the name of Rider Salmon to teach us English and reopen us to the world of modern writing. To what was being done by Eliot, Auden, Spender, and Virginia Woolf. But I was still fretting…I wanted to get out of the family environment and school. And when I heard there’s an important school of architecture in London, the AA School, and that they didn’t require A levels, I was keen to join it.

So, after the first year, much to the disappointment of the principal and Rider Salmon, who wanted me to get into Cambridge or Oxford, I somehow set my mind on just leaving the country. And so, I didn’t complete the course, and I found myself on a ship sailing to London in June-July 1957.

Then, I finally decided to settle here in 1970. I was doing quite well in London after Oxford…yet after my first year at Oxford, I came back and then returned and stayed there till 1969. At that time, I met Veronik and her daughter, I was living with them, and then all three of us landed up here in 1970.

Urna: When and how did the poems in Land’s End take shape? You’d even finished a play; I think by August of 1958. What did you carry into your poetry from playwriting? Tell us a little bit about Trying to Say Goodbye and being drawn to the prose poems of Rimbaud.

Adil: I began taking the writing of verse seriously shortly after I arrived in London in 1957. This had to do with the isolation I felt from not fitting into a new society. The verses I composed at the time were in free verse, you’ll find an example in ‘Seventeen’, the first poem in Land’s End. But I soon grew interested in composing verses that were metrical, formal, and rhymed.

The dialogues in ‘Jian’, the play I began writing in 1958, are in prose, but when it came to making its young protagonist Jian speak to himself, his soliloquies, I found I was writing free verse again. Like:

“A rebirth's agony is near Hold me, Father, It is near Near than my voice is To my throat My sight is to my eyes Hold me, Father, It is near I fear my safety on its Foreign ground. It has Empty chasms for my feet.”

So, you could say that my attempts at writing a play and writing a verse weren’t mutually exclusive activities. Both fed into each other at that time. A few prose poems that served as reminders of my fascination with Rimbaud’s works and life were present by the time, I started collecting many unpublished poems much later—around 2009. That was in the late 1950s, when I discovered him, and later too.

Urna: Do you think someone could write poetry if they do not feel the pull of emotions strongly? What is your take on writer’s block? What advice would you give to someone stuck in a rut, unable to write poetry?

Adil: I think the pull of strong (or mild) emotions, or rather, a strong or mild emotional disturbance, is essential to begin a poem; it’s a start. The rest—the attention, the drafts, and the revisions—demand mental processes that have less to do with the original disturbance. You can’t leave these to your emotions alone.

As for writer’s block – I don’t know what to say. I know many feel that writer’s block accounts for the gap of 34 years between my books Missing Person and Trying to Say Goodbye, but no, I continued to write poems during that time, but those didn’t satisfy me. And I wrote prose for several newspapers and magazines, some of it collected in books.

Perhaps those who feel they have writer’s block should write anything, not necessarily the poem or piece of fiction or non-fiction they want to write, but anything—not necessarily to get published but for themselves. That practice might eventually free them to write what they deeply want to.

***

Urna Bose reads a poem by Adil Jussawalla

***

Five Poems by Adil Jussawalla

Poem # 1

House

Wake up. Don’t you want to see me go? What you heard in your sleep were sledgehammers. Did you think it would never happen? You’d read the notice. Good morning. I was condemned for a fault I can’t remember. You have memory, The room into which everything you see once goes. Houses don’t come with that extra. Where do the things we see go? See my rooms now, their outer walls gone, My secret eyes With nothing left in them. See my still-polished staircase rising To ends that can never be met: Doorways that draw a blank. I was raised to think I’m no pushover, But you see, I am. All houses are fall guys. The plans you lay to set us up Touch our very foundations. Stranger, still looking for home, Who watched me for months, Pay attention: I’m setting you free. Your future’s got nothing to do with what’s happening to me. Your universe was built to dance on a pin, Mine to stay still. Tell your guru Stillness did a house in. Learn balance with nothing to stand on. Though you’ve lost heart, lost ground, Go rootless, homeless, but balance.

From: Trying to Say Goodbye Poems Publisher: Almost Island Books

Poem # 2

English Lesson

This is a stick of chalk. See, white powder spilling away from the side of its mouth is drawing a skull. Say it please…skull. It can’t draw a rose. Young Europeans mostly, in class. Across their faces my wry reflections run like water on glass. This is a tank. This is – This is a stick of chalk. With it I draw pictures. It can’t draw the war in India, it can’t draw certain pictures. There’s only one God, there’s only one Good, and both must be learned without pictures.

From: Trying to Say Goodbye Poems Publisher: Almost Island Books

Poem # 3

Urdu Lesson

While Urdu poets bared their patriotic souls behind mikes called Chicago, and China left our border with bodies no one cared for, I read Wilfred Owen, and found his view of death vaguely familiar, Buddhist perhaps, from an altitude indifferent to vengeance but caring, all the same, for what vengeance did to men Thunder in the mountains, fear in Oxford’s streets – a nuclear strike set off by Cuba imminent – and in my heart a bitterness that spoke no language. Not a word. None of the magic I picked up in Bombay Nothing of the Urdu that flew out of Chicago.

From:Trying to Say Goodbye Poems Publisher: Almost Island Books

Poem # 4:

Ballet

The spider’s web above the lamp we bought before our marriage sways in a light breeze. One thin arm grips one of the lamp’s chains, the other another. One of its legs points up, the other down. I don’t see the spider, you don’t see the web. It’s our home after all. We’re dancing, we’ve danced.

From: Trying to Say Goodbye Poems Publisher: Almost Island Books

Poem # 5

Deity

If Egypt had a colour, it sits in the garden cat’s eyes – green. If the Nile had a colour apart from the two we call it, it’s there in the stare the cat’s eyes fix on us approaching it, gently approaching it – red. She knows everything, is always in place, waiting for her feeder to arrive exactly at four, lay down food at our feet.

From: Earth – Poems for Veronik Publisher: Paperwall Publishing

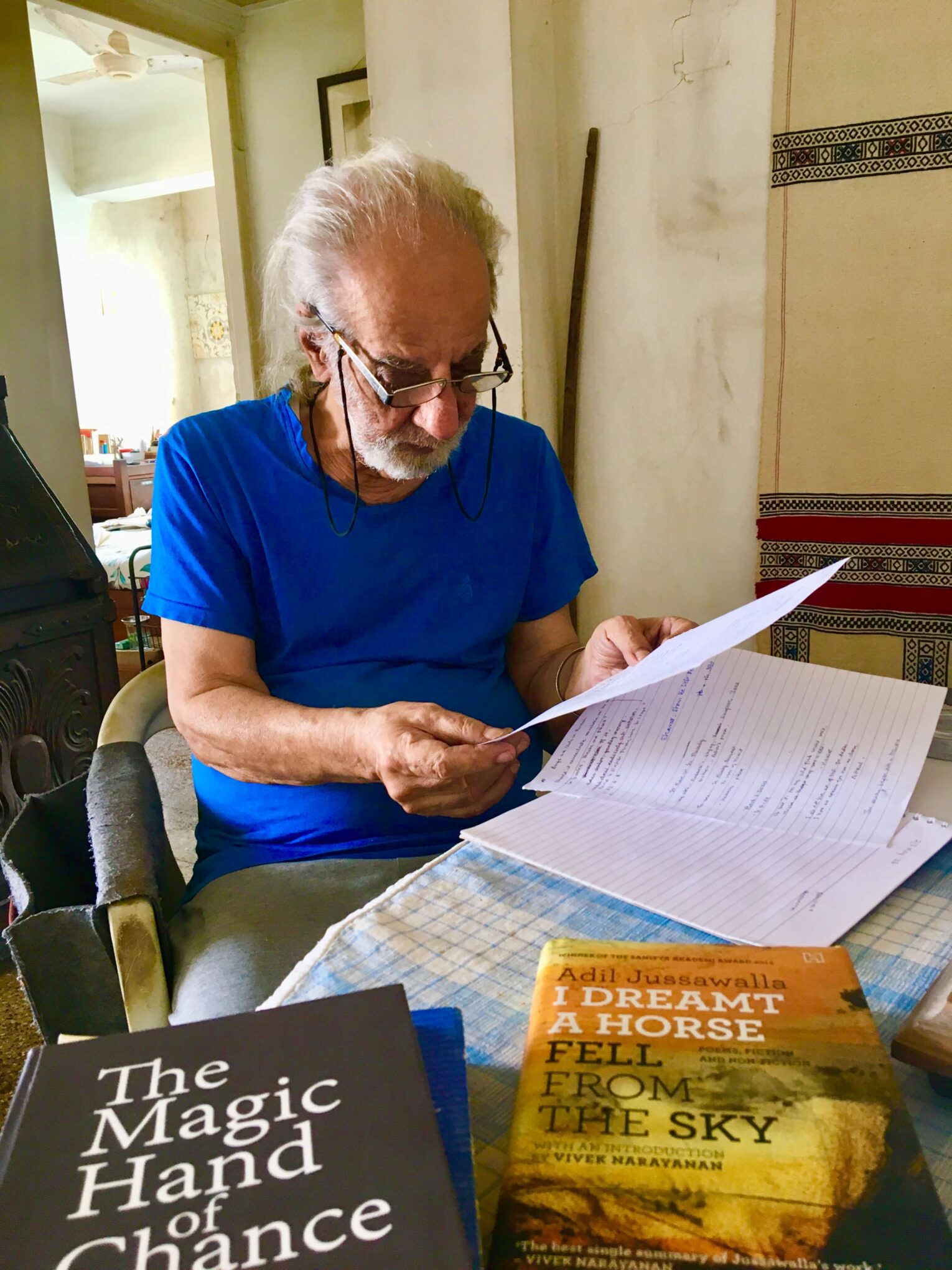

Photos sourced from Adil Jussawalla

A fascinating article! Adil has been a friend and mentor for many years. He is always thought provoking. And I enjoy his poems.

Thank you so much Urna for this interview!

Adil is such a beautiful being! I’m so sorry that english is not my language, I’m french and I read his poems through this gap…Anyway, this man has brought so much to my familly, I discover this more and more as time passes.