Reading Time: 11 minutes

In the semi-quincentennial anniversary (250 years), of the first Renaissance Man of India, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Different Truths pays a tribute to the polymath social reformer, who eradicated Sati and stood up for the rights of the widows and women. An exclusive by Nachiketa.

The second half of the eighteenth century, when the Mughal glory was yet to extinguish, people of India in misery under foreign rulers for two centuries lived like subhuman subject, mostly. A broken country, full of people, who were separated, ignorant, weak in stamina. Foreign adventurer once again as predator – this time through British takeover. Dutch and French could not compete. Robert Clive finally emerged victorious over the other foreign traders. Princely states were surrendering routine wise, Calcutta port became more important than Madras and Bombay, as the trade center. Calcutta is significant as the headquarters of East India Company.

The Company was attentive on earning high profit, less attentive on social intricacy of people. It did not interfere with social customs, whatever darkness there. They enjoyed the internal conflict among the natives. The Company earned a monopoly on Indian trade approved by the parliament. Some royal fortunate people existed in each state. They were enlightened, wealthy, and educated of the system. Krishna Chandra Banerjee of Murshidabad was among such fortunate people, who were awarded with the title Roy by the government. The title was inherited by the descendants. Krisna Chandra was a forefather of Ram Mohon.

Resistance Against Polygamy and Dowry System

Ram Mohan Roy was born in Radhanagar, Hooghly District, Bengal Presidency, in a Kanauji Kulin Brahmin family, in 1772. Kulinism was notorious for polygamy and the dowry system, both of which Rammohan voiced against and led the resistance movement. His father, Ramkanta, was a Vaishnavite, while his mother, Tarini Devi, was from a Shaivite family. He followed traditional, Sanskritised education, as well as Arabic and Persian, for worldly living to represent the Court service. Ram Mohan Roy was married three times. His first wife died early. He had two sons.

Scholars opine that Ram Mohon Roy is the Father of the Indian Renaissance, often called the Father of Modern India for his relentless activity in Indian social reform…

Scholars opine that Ram Mohon Roy is the Father of the Indian Renaissance, often called the Father of Modern India for his relentless activity in Indian social reform, theorization of Hinduism to a new dimension. He led a movement for the rights for colonial India. And his influence on the British government was palpable. Roy was the founder of the Brahmo Sabha movement, in 1828, which in due course established as the Brahmo Samaj, having an impact on the socio-religious reform movement of Bengal. Bramho Samaj has contributed to Indian modernisation.

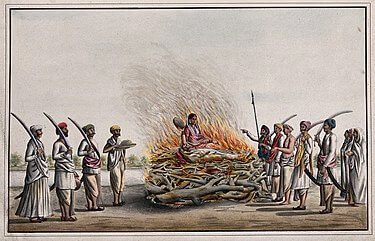

Bengali women remember him. He took courage for the abolishment of the practice of Sati, the cruel funeral practice wherein the widow was forced to sacrifice her life on the funeral pyre of her deceased husband. Raja Ram Mohan Ray was the first activist and a gender revolutionary for the cause of women. He campaigned for women’s rights, the right of the widows to remarry, and the right for women to hold property. He supported the education of women. He actively opposed the practice of polygamy. He advocated the study of English, Science, Western Medicine and Technology.

Roy, the first person to realise and identify that English-language education was necessary for the country, instead of the traditional Indian education system in vernacular language alone. He campaigned for the appropriate utilisation of the government funds to support traditional schools. He established some modern schools to popularise a modern system with science and English. The Mughal Emperor awarded him the ‘Raja’ title.

Outlook on Modern Education

His outlook on modern education is worth considering even now: “If it had been intended to keep the British nation in ignorance of real knowledge, the Baconian philosophy would not have been allowed to displace the system of the schoolmen, which was best calculated to perpetuate ignorance. In the same manner, the Sanskrit system of education would be best calculated to keep this country in darkness, if such had been the policy of the British Legislature. But as the improvement of the native population is the object of the Government, it will consequently promote a more liberal and enlightened system of instruction, embracing mathematics, natural philosophy, chemistry, and anatomy, with other useful science[s] which may be accomplished with the sum proposed by employing a few gentlemen of talents and learning educated in Europe, and providing a college furnished with the necessary books, instruments and other apparatus.” (To Governor General, Lord Amherst, Dec 1823)

Education: A Weapon of Enlightenment

With education as a weapon of enlightenment, he thought of eradicating the superstitious social weeds of malpractices. To implement the desired social reforms, he established the Hindu College, at Calcutta (1817), assisted by David Hare, founded the Anglo-Hindu school (1822), Vedanta College (1826) with synthetic course of Eastern and westerner, helped by Rev. Alexander Duff to establish General Assembly’s Institution (renamed Scottish Church College) providing land.

He coined the term Hinduism first but was the co-founder of Calcutta Unitarian Society.

He deduced Vedanta School of philosophy from the Upanishads’ concept. He practiced Secularism, while he spoke on the unity of God. He coined the term Hinduism first but was the co-founder of Calcutta Unitarian Society. Correspondences revealed he was enamored with Unitarianism through contacts with British and American Unitarians. His admiration for Unitarian ethics had a political concern probably for the Indian mass rather than his own interest. Practically, the potential social benefits of Unitarian contacts were needed in the field of education considering the felt-need of that time.

He amalgamated the ideas of East and West and hybridised the Occidental and Oriental concepts. And preached the unity of God. He promoted a neo-Hinduism of the then era crystallising through social reformation with rational thinking and practical ethics. His writings also sparked interest among British and American Unitarians. Raja Ram Mohan Roy raised voice against idol worship, orthodoxy of Sanatan rituals, social bigotry, conservatism, and superstitions, ignoring traditional family orthodoxy, leading to distance and drift between his family and him. Emotion made him traveller and true seeker to wander among the Himalayas, Tibet part of the country.

Polyglot and Polymath

The most wise and vast scholar, he was the polyglot and polymath. He had learned Sanskrit, Persian and Bengali in early childhood in his village school. He studied Persian and Arabic in Patna and practiced Sanskrit Sastra, the Vedas, and the Upanishads, in Kashi. The chronology of his schooling is debatable and controversial. He studied the Kalpa Sutra and other Jain texts. He took a keen interest in contemporary politics and followed the cause of the European and French Revolution. In 1815, he founded the Atmiya Sabha, and, in 1828, he established the Brahmo Samaj. His journey to the United Kingdom, in 1830, as an ambassador of the Mughal Empire, to ensure that Lord William Bentinck’s Bengal Sati Regulation, 1829 was not overturned.

Co-authored Maha Nirvana Tantra

From 1809 to 1814, he served under the Revenue Department of the East India Company (“Writing Service”, commencing as private clerk “munshi” to Thomas Woodroffe, Registrar of the Appellate Court, etc.) and acted as a political agitator and agent, representing Christian missionaries. Prior to this, in 1797, Ram Mohan acted as a money lender, to impoverished Englishmen of the Company. Ram Mohan also practiced as a pundit in the English courts for livelihood. “Maha Nirvana Tantra” (Method of the Great Liberation), a text to “the God is one and true” was the result of triad-Ram Mohan, Hariharananda Vidyavagis, a Tantric, and William Carey, in 1797. Carey, in 1793, came to India, published the Bible in Indian languages, aiming at propagation of Christianity among native masses. He had to associate with Bengal Brahmins and Pundits to translate the Bible. Actually, Hariharananda introduced Ram Mohon to Carey.

We thus observe multiple influences of culture on the development of his theological persona.

We thus observe multiple influences of culture on the development of his theological persona. Roy had his Arabic instruction, he discarded Western thought at the end of his life. Although, at the onset of the Brahmo Samaj establishment it played an important role. Contradictory though, his inner theology was unchanged, maintaining distance from orthodoxy. He practiced Hinduism, influenced by Vedantic theology, or a Deist or Theist, throughout his life. Controversy also continued that he wrote tailormade topics for intended audience (Demont Killingly) to use different religious philosophies during writing in Persian (Islamic), Sanskrit and Bengali (Vedanta), and English (Biblical), (Zastoupil 2010, cited by Ian Brooks Reed, Thesis 2015). He might have associated with Buddhist philosophy in Tibet and Jaina philosophy in Rangpur (the then Jaina/Muslim mercantile centre).

Contemporary English philosophers influenced him greatly. Sugirtharajah writes that, “The later works of Roy show his acquaintance with contemporary western thinkers such as Locke, Hume and Bentham.” (Sugirtharajah, 53) Then later in life, possibly in connection to the founding of the Brahmo Samaj, Roy might have made a distinct turn away from the Western thought.” (Sugirtharaja, cited by Reed, 2015). But Ray carried principal theological school, Advaita theology, for most of his life as revealed from Bengali works., Roy’s view was that Upanishadic Advaita theology, being an ancient concept rather than religious concept, was the highest form of religion.

The Seed of Monotheism

One can guess that seed of monotheism sown in his mind from Arabic studies. He authored Tuhfat-ul-Muwahhidin, or ‘A Gift to the Monotheists’. As Crawford (cited by Reed, 2015) explains, “…in a radical sense, he could not go home again. The new knowledge of Sufi philosophy reinforced by the Vedanta, had alienated him from the popular Hinduism represented by his family’s altar.” His campaign against Saguna worship (idolatry) had started earlier. Here is the spark of his Universalism. In an intimate conversation with his wife, he opined, “Cows are of different colours, but the color of the milk they give is the same. Different teachers have different opinions, but the essence of every religion is to adopt the true path.” (Collet) Crawford informed, Roy’s Translation of an Abridgment of the Vedanta, “a phenomenon in the literary world,” published in the Government Gazette, in 1816, quoting that it “displays the deductions of a liberal and intrepid mind.” And this publication brought Roy to the attention of Christian missionaries, leading to an American review of Raja’s anti-idolatrous writings.”

Brahmo Samaj addressed him as a nationalist reformer…

Brahmo Samaj addressed him as a nationalist reformer, who had a three-fold mission of Unitarian reaction of the Hindu Shastras from the Vedanta and the Mahanirvana Tantra. the Tuhfat-Ul-Muwahhiddin and the Monozeautul Adiyan, and conversion with Christian Missionaries.

First Indian to Fight for Press Freedom

His most popular journal was the Sambad Kaumudi. He was the first Indian, who fought for press freedom. We remember the appeal to colonial government and the first communication ever addressed to a British monarch by an Indian, “It is well known that despotic Governments naturally desire the suppression of any freedom of expression which might tend to expose their acts to the obloquy which ever attends the exercise of tyranny or oppression, and the argument they constantly resort to, is, that the spread of knowledge is dangerous to the existence of all legitimate authority, since, as a people become enlightened, they will discover that by a unity of effort, the many may easily shake off the yoke of the few, and thus become emancipated from the restraints of power altogether, forgetting the lesson derived from history, that in countries which have made the smallest advance in civilisation, anarchy and revolution are most prevalent — while on the other hand, in nations the most enlightened, any revolt against governments which have guarded inviolate the rights of the governed, is most rare, and that the resistance of a people advanced in knowledge, has ever been—not against the existence—but against the abuses of the Governing power.” (1824, Roy appealed against the ordinance of the strict restrictions on the press imposed by the Government of Bengal).

Tagore remarked, “[Roy] had the full inheritance of Indian wisdom. He was never a schoolboy of the West…”

Tagore remarked, “[Roy] had the full inheritance of Indian wisdom. He was never a schoolboy of the West, and therefore had the dignity to be a friend of the West.” And Gandhi’s view on Roy, “I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.”

Institutional poverty of India is being placed in historiography in the context of current National poverty and its causes was analysed by Dadavai Nouroji (1876) in “poverty and UN-British rule in India” through Drain theory or economic drainage method. Sequential works were done by Alexander Dow, Lord Cornwalis, Edmund Burke and others. Ram Mohon was the first Indian to explore the source and mechanism of drainage around 1830 (Dev Roy, 1987).

Inconsistent Economic Views

Bhattacharya (1975) opined that Roy’s intellectual on economics was debatable for his strong advocacy for unrestricted residency for colonisation and assisted indigo planters. “He admitted that the permanent settlement had failed in its principal objectives and yet he never spoke of discarding it and only urged that there should be some sort of a revision of it …. Ram Mohan appealed “to any and every authority to devise some mode of alleviating the present miseries of the agricultural peasantry of India” and yet he pleaded strongly for the unrestricted settlement of Europeans in India, for he believed that the European indigo planters performed considerable good “to the generality of the natives of this country”. Ram Mohan’s economic views were not free from inconsistencies …. In fact, Ram Mohan’s strong plea for the indigo planters punched a hole in his radicalism…. To return from this useful digression to our main theme, it must now be said that Ram Mohan, inspite of his being the most inquiring and the most ‘modern’ man of his day, seemed to have unwittingly slipped into advocacy of the indigo planters and European settlement in India”.

Roy, the first modern man who wrote and acted for women’s cause. More than any modern feminist…

Roy, the first modern man who wrote and acted for women’s cause. More than any modern feminist, “… Women are in general inferior to men on bodily strength and energy; consequently, the male part of the community, taking advantage of their corporeal weakness, have denied to them those excellent merits that they are entitled to by nature, and afterwards they are apt to say that women are naturally incapable of acquiring those merits….

“Secondly, you charge them with want of resolution, at which I feel exceedingly surprised: for we constantly perceive, in a country where the name of death makes the male shudder, that the female, from her firmness of mind, offers to burn with the corpse of her deceased husband; and yet you accuse those women of deficiency of resolution…. Thirdly, with regard to their trustworthiness, … I presume that the numbers of the deceived women would be found ten times greater than that of the betrayed men….one man may marry two or three, sometimes even ten wives and upwards; while a woman, who marries but one husband, desires at his death to follow him forsaking all worldly enjoyments, or to remain leading the austere life of an ascetic…. Observe what pain, what slighting, what contempt, and what afflictions their value enables them to support! ….. to death. These are facts occurring every day, and not to be denied. What I lament is, that seeing the women thus dependent and exposed to every misery, you feel for them no compassion that might exempt them from being down and burnt to death.”

Decade-long Battle Against Sati

The decade-long battle to ban Sati through government decree, from 1818 to 1829, would be the definitive activism of Roy’s life — even more seminal than the founding of the Hindu Unitarian Brahma Samaj or inspiring the creation of the Hindu College (from where, once it started, he was ousted by wealthy Hindu orthodox donors) as a haven for training in modern science, philology, and ethics. The fight against Sati would pitch Roy against some of the most powerful vested interests in the country, influence so strong that even after a Governor General (the Marquess of Hastings) tried to make it illegal, it continued. Such was the outcry from the orthodoxy — not just the powerful clerics but also their aristocratic and wealthy supporters — that the order to stop Sati had to be withdrawn. It was only after a decade of relentless pressure from Roy and his fellow liberals, many of whom also co-founded the Brahma Samaj with Roy, that Sati was finally abolished, in 1829, by Governor General William Bentinck.

In 1831, Ram Mohan Roy traveled to the United Kingdom as an ambassador of the Mughal Emperor. His assignment was to plead for his pension and allowances. He never returned to his motherland. Raja Ram Mohan Roy passed away on September 27, 1833, at Stapleton, near Bristol, due to meningitis.

References

1. Ian Brooks Reed, Ram Mohan Roy and The Unitarian, Florida State University College of Arts and Science, 2015

2. Crawford, S. Cromwell. Ram Mohan Roy: Social, Political, and Religious Reform in 19th Century India. New York: Paragon House, 1987.

3. Collet, Sophia Dobson. The Life and Letters of Raja Rammohun Roy. Ed. Hem Chandra Sarkar,

Calcutta, 1914

4. Rama Dev Roy, Some Aspects of the Economic Drain from India during the British Rule,

Social Scientist Vol. 15, No. 3 (Mar., 1987), pp. 39-47 (9 pages)

6. Subbhas Bhattacharya, Indigo Planters, Ram Mohan Roy and the 1833 Charter Act

Social Scientist, Vol. 4, No. 3 (Oct., 1975), pp. 56-65

Feature picture from Pinterest.com

Insert picture from Wikepedia.org