Prof Nandini, on DifferentTruths.com, explores Jayanta Mahapatra’s Odia poetry through Gopa Ranjan Mishra’s translations, blending cultural intimacy with global academic resonance, in her erudite research paper.

AI Summary:

- Cultural Re-inscription: The research highlights how Mishra’s translations preserve Odisha’s unique topography and mythology, moving beyond literal rendering to cultural stewardship.

- Theoretical Framework: Utilising Venuti and Spivak, the study argues that “foreignization” and “ethical responsibility” protect the poems from being domesticated or exoticised.

- Existential Inquiry: Mahapatra’s themes of mortality and history are reimagined as a “third space” where silence and revelation meet.

For most people, tragedy signifies an existence immersed in pain and suffering. For Jayanta Mahapatra (JM), however, the tragic paradox of life is more intricate; it lies in the simultaneous impulse to yield to one’s suffering and the need to transform that suffering into words. In poems such as “Hunger” and “Dawn at Puri,” Mahapatra does not merely lament human misery; he wrestles with it, shaping anguish into a quiet moral inquiry. The starving fisherman in “Hunger” embodies both physical and existential deprivation, while the widows at Puri’s temple foreground a haunting awareness of mortality and resignation. Through such images, Mahapatra turns pain into an act of introspection, suffering becomes not a spectacle, it’s a medium for ethical and spiritual questioning. Yet, Mahapatra’s vision does not end with despair.

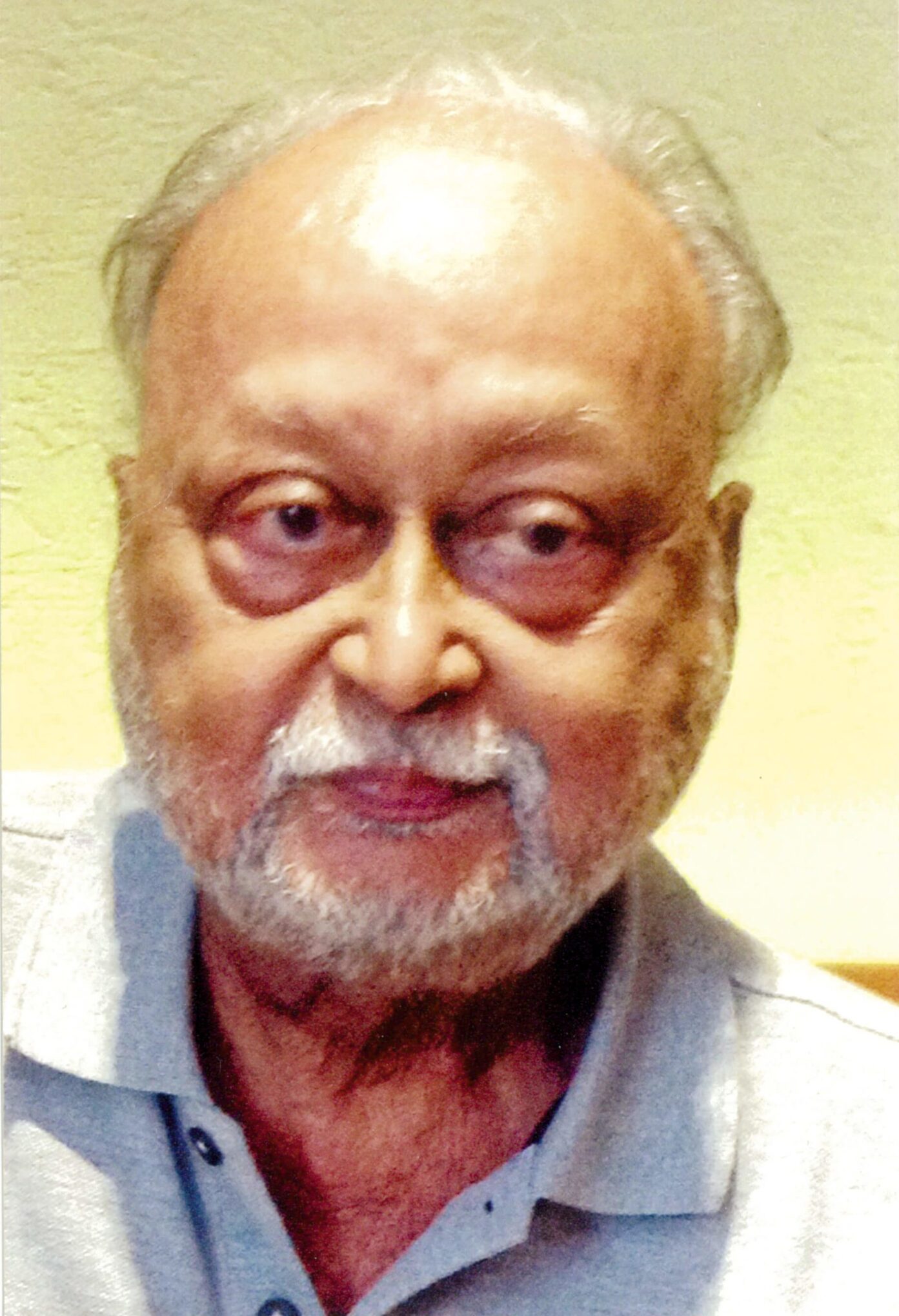

His later poems, such as “The Whiteness of Bone” and “A Missing Person,” suggest the possibility of transcendence, a movement beyond suffering and expression, where silence is evocative. It is in this gesture of stillness and inward illumination that Mahapatra finds kinship with Gopa Ranjan Mishra (GRM), his fellow poet, translator, confidante, friend and critic. In the translated poems like “My Grandmother’s Cooking” or “The Insane Light of the Odisha Famine of 1866,” the translator, Professor Gopa Ranjan Mishra, transforms Mahapatra’s pain into moments of revelation, making the poems multi-layered, as Mahapatra would have wished his poems to be read or re-read.

Mahapatra’s language turns towards the mystical, suffering, but for Mishra, Mahapatra’s language is reimagined as a threshold to spiritual clarity and self-discovery.

Together, Mahapatra and Mishra suggest that poetry should not seek to make suffering beautiful, but to release it from its binding hold. When art no longer serves as a vessel for glorification of pain, it becomes an act of freedom, a passage towards inner renewal, where silence, compassion and wonder replace the inevitability of tragedy.

This research attempts to negotiate cultural intimacy with a view to translation as the re-inscription of poetry, critically and pedagogically engaging with Jayanta Mahapatra’s poems translated from Odia to English by Gopa Ranjan Mishra. Translation, in this case, is not purely a linguistic exercise; it’s an act of cultural negotiation, especially when it deals with a poet like Jayanta Mahapatra, whose work is steeped in the topography, mythology and cultural ethos of Odisha.

This paper explores how Gopa Ranjan Mishra’s English translations of Mahapatra’s Odia poetry transcend conventional translation practices by engaging in a process of re-inscription, one that preserves cultural intimacy while making it accessible to global readerships.

Drawing upon key translation theories, from Walter Benjamin’s concept of “the afterlife” of the text to Lawrence Venuti’s notions of domestication and foreignization, as well as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s emphasis on ethical responsibility, the paper argues that Mishra’s work constitutes a rare instance of metaphoric, cultural and transcreative translation that does justice to Mahapatra’s uniquely Odia vision, both of them being bilingual poets.

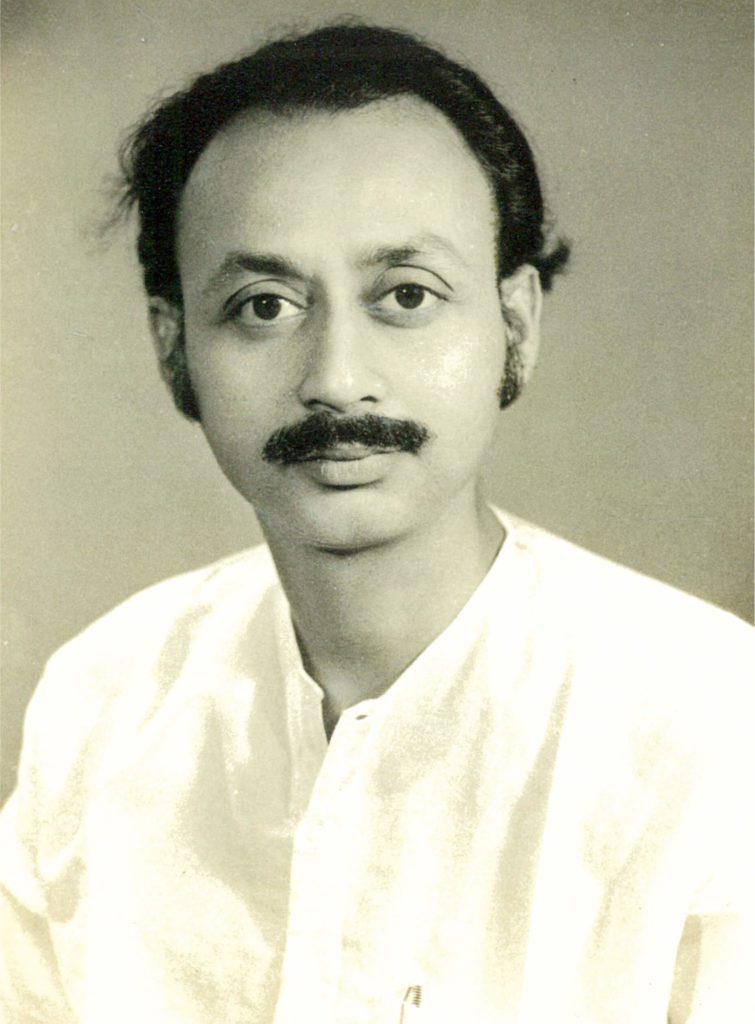

Jayanta Mahapatra (1928–2023), the first Indian poet writing in English to win the Sahitya Akademi Award, also wrote extensively in his mother tongue, Odia. While his English poetry has been widely anthologised, his Odia work has received comparatively less attention beyond Odisha. This imbalance arises in part from the daunting task of translating Mahapatra’s Odia poetry, which is embedded in the regional landscapes, myths, and social textures of Odisha.

Gopa Ranjan Mishra’s translations of Mahapatra’s Odia poems into English emerge as exemplary acts of artistic stewardship. By negotiating between fidelity to source culture and accessibility for a global audience, Mishra offers a translation strategy that is simultaneously close to the original, evocative and transformative. This paper contends that Mishra’s translations enact what we might call “re-inscription”; they do not purely render lexicon after lexicon, but rather re-inscribe cultural memory and intimacy into another linguistic system.

This research makes a humble attempt at understanding the translator’s challenges and defining his pedagogy, with the following research objectives, while looking at Mahapatra (for the first time in my lifetime) through the lens of another poet, Gopa Ranjan Mishra:

- Topography and Geography: Odisha’s landscape, its estuaries, temples, mangrove forests, rivers like the Mahanadi, and the coastal rhythms of Cuttack and Puri, form the pulse of Mahapatra’s work. Place-names like “Chilika,” “Lingaraj,” or “Jagannath Puri” are not mere references but carriers of layered meanings. Translating them requires a nuanced grasp of both geography and its cultural connotations.

- Mythology and Culture: Mahapatra’s poetry invokes the living myths of Odisha, Lord Jagannath’s annual Rath Yatra, the Shakti cults, folk deities, and rituals. These are culturally dense phenomena that resist direct English equivalents.

- Oral and Rhythmic Qualities: Odia, as a language, has a distinct cadence, with soft consonants and a musicality shaped by its folk and devotional traditions. Capturing these prosodic effects in English without flattening the texture is a translator’s nightmare.

- Cultural Intimacy: As Spivak emphasises, translation must involve an “intimate reading” of the original text. Without a rootedness in Odia culture, the translator risks producing an alienating or exoticising effect.

GRM’s translation of JM is nothing less than a cultural negotiation. Mishra’s translations display what Lawrence Venuti calls a “foreignising” ethos; he resists excessive domestication and instead preserves the Odia-ness of Mahapatra’s poetry, allowing English readers to encounter its cultural difference. Yet Mishra also demonstrates a deep commitment to what André Lefevere terms “refraction”, adapting and reframing texts for new audiences while retaining their original aura. Key features of Mishra’s approach include metaphoric translations. Mishra renders culturally embedded metaphors into evocative English images without diluting their semantic richness. For instance, an Odia image of “the conch’s broken breath at dawn” might appear in English as “the cracked breath of the conch at daybreak,” maintaining the sacred tone. Talking about cultural translation, Mishra does not shy away from retaining Odia words like “Mahaprasad,” “Pattachitra,” or “Baul”, supplementing them with subtle contextual cues. This allows for what Homi Bhabha calls a “third space” of enunciation, where cultures meet without erasure. Vis-à-vis the ideas of transliteration and transcreation, when cultural markers cannot be translated, Mishra employs transliteration and transcreation (creating parallel metaphors in English that evoke the same affective response).

This hybrid strategy aligns with Haroldo de Campos’s notion of “transcreation,” which prioritises aesthetic and cultural equivalence over literal fidelity. For Mishra, translation is an ethical responsibility. Echoing Spivak, Mishra’s translations are an act of ethical solidarity. They neither patronise nor exoticise Odisha’s cultural matrix; they invite readers to dwell in the interiority of the texts. Topography, mythology and culture of Odisha in Mahapatra’s Odia poetry, especially in collections like Baya Raja and Bhitara Ghara, are inseparable from the landscapes and rituals of Odisha. The sea at Gopalpur, the temple town of Puri, the tribal hinterlands of Koraput, and the rice fields of Cuttack recur as living presences. These places are not backdrops; they are personified protagonists.

Mishra’s translations honour this by retaining place-names and cultural specifics rather than flattening them into generic equivalents. For instance, the Jagannath cult is not merely a religious motif; it is a metaphor for identity, historical trauma and cyclical renewal. Translating Jagannath as “Lord of the Universe” would strip the word of its Odia resonance; Mishra astutely retains “Jagannath” and weaves its aura into his English syntax. This approach reflects Antoine Berman’s idea of ‘ethnocentric violence’ in translation, the tendency of translators to erase foreignness. Mishra resists this violence, preserving cultural intimacy through strategic foreignization.

This research deploys three key theoretical lenses to frame Mishra’s translations. Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator” (1923), where Benjamin argues that a translation gives a text an “afterlife” by carrying it into another language. Mishra’s translations offer Mahapatra’s Odia poetry such an afterlife, extending its reach without erasing its soul. Next, Lawrence Venuti’s Domestication/Foreignisation (1995), when Mishra’s translations lean toward foreignisation, retaining Odia names, symbols, and rhythms, while also providing enough contextual transparency to guide non-Odia readers.

Finally, Spivak’s “Politics of Translation” (1993) looks apt and contextual. Spivak underscores the translator’s ethical duty to inhabit the text intimately, respecting its cultural and gendered dimensions. Mishra’s insider position in Odia culture allows him to fulfil this duty more effectively than an outsider could. Mishra’s work emerges as a re-inscription, a rewriting that restores the original text’s affective and cultural textures in another linguistic world.

The success of Mishra’s translations stems from his dual rootedness as well as his deeply personal rapport with Mahapatra, apart from his deep immersion in Odia language and culture on one hand, and a sophisticated command of English poetic idioms on the other. This rare combination enables him to navigate Mahapatra’s layered texts with both fidelity and creativity. I may be allowed by Mishra here to quote a few text messages that Mahapatra had lovingly sent Mishra (who, he dearly addressed as ‘Gopa’), who, subsequently, had shared a few with me. Mahapatra wrote Mishra, “Gopa, my apologies. Death is a part of life. Let’s not turn it into melodrama. So please don’t send such syrupy poems.”

Mishra sent me a message approximately after the death of Mahapatra, “JM wished that the first poem in the collection of his translated poems should be the poem in which he has spoken about his age and has expressed his apprehension that he may not complete his 95th year. And in fact, that happened. Two months before his birthday, he passed away.” There was this mystical sense of acceptance of death; thus, there has been a sheer death-consciousness in Mahapatra’s poetry. “His poetic style is characterised by its lucidity and precision, employing vivid imagery and metaphors to convey complex themes” (Hazarika 14). In the poem “Needless”, Mahapatra writes,

Death is always of someone else’s It’s only another’s.

As one is struck with fear

When one looks into the mirror of things past— one’s reflection changes;

Would it throwback somebody else’s face?

What was unsettling me that evening, on the face of my dead father?

The mystery of love

That lay shut within four walls? Or was it some courage of mine

Which I thought would save me from myself?

All mysteries turn helpless

At the sight of the empty skins of dead animals,

Somehow grief doesn’t come along as before...

Mahapatra’s poem “Needless” is an existential reflection on death as both estrangement and recognition, where the poet confronts mortality not as a metaphysical certainty but as an elusive mirror of selfhood. The poem dramatises what Heidegger calls ‘Being-toward-death’, the awareness that death is always both intimate and alien, “always of someone else’s,” yet foreshadowing one’s own disappearance.

The shifting reflection “Would it throwback somebody else’s face?” captures the dissolution of identity, where the self becomes fragmented in memory and grief. The father’s dead face becomes a metaphorical screen onto which the poet projects his own finitude, echoing Freud’s notion of ‘the uncanny’, the return of what is familiar yet terrifyingly strange. Mishra’s translation extends this tension between presence and absence, turning Mahapatra’s Odia rootedness in familial death-rituals into a more universal phenomenology of loss. “Needless” reveals how Mahapatra’s death-consciousness transforms mourning into epistemology, a reeking realisation that death is not the end of life, but the mirror through which the poet measures the fragile, shifting boundaries of being.

Like Mahapatra, Mishra understands Odisha not as a spectacle but as a lived experience, the smell of mahua flowers, the chants at Jagannath’s temple, the monsoon’s cadence over Mahanadi. His translations carry the cadences of Odia syntax while adapting them into supple English lines, a feat comparable to A.K. Ramanujan’s translations of classical Tamil poetry. Mishra’s ability to deploy transcreation when needed ensures that Mahapatra’s metaphors remain resonant rather than brittle in English.

Thus, Mishra’s translations do not represent Mahapatra’s poetry; they re-inscribe its cultural intimacy for a global readership without betraying its Odia core. Translation of regional Indian poetry/Bhasha poetry into English is fraught with the danger of loss: loss of rhythm, loss of culture, loss of intimacy. Yet Mishra’s translations of Mahapatra’s Odia poetry demonstrate that such loss can be minimised when the translator engages in a process of metaphoric, cultural and ethical translation. By drawing upon strategies of transliteration, transcreation and foreignisation, Mishra negotiates the cultural intimacy of Mahapatra’s poetry and re-inscribes it in a global linguistic space. His work offers a model for future translators of Indian literatures, underscoring that translation is a linguistic task, an act of cultural custodianship and aesthetic stewardship. In the poem, “The Insane Light of the Odisha Famine of 1866”, Mishra translates the pain of a region in the words:

That sunlight that blazed like a sharp-edged sickle On Odisha’s back

Is no more with us,

Its body was fire, and its feet was ash,

A harsh, glaring light on a strange horizon Some hundred and fifty years ago.

And what kind of life do I want to live today? What dream should I dream?

So as to live in peace with some ease Or live like such a man

Who would get along well with others.

Even if the sky has abandoned all its blue And it catches fire

And the tree is reduced to a bare, unsightly skeleton

And a lone spent-up cloud of darkness

Is not able to sail any further in the sky.

Mahapatra’s poem “The Insane Light of the Odisha Famine of 1866” reopens a historical wound, the catastrophic famine that claimed nearly a third of Odisha’s population under British colonial administration. A New Historicist reading situates this poem in the interstices of text and history, seeing it not just as an isolated act of imagination but rather as a cultural artefact, deeply entangled with colonial archives, economic policies and the collective memory of suffering. Here, history is the text and the context of the great famine and colonial discourse.

New Historicism insists that history is not an objective record but a textual construct shaped by power. The 1866 Odisha famine, marginalised and minimised in colonial records as an administrative failure, is revisited here as an embodied trauma. Mahapatra’s “sunlight that blazed like a sharp-edged sickle on Odisha’s back” reworks the language of light, traditionally a metaphor for enlightenment and progress, into one of violence and violation.

The ‘light’ becomes an instrument of colonial domination, the sickle-like sun scorches the land, reflecting both imperial exploitation and nature’s complicity in human suffering. The poet counters the colonial archive by producing a counter-history, written in the idiom of pain and loss. The latter part of the poem works as counter-memory for me as a reader.

In the New Historicist framework, literary texts engage in a dialogue with the silences of official history. The Odisha famine rarely found expression in mainstream historiography; Mahapatra’s poem performs the work of remembering the unremembered. By invoking the “harsh, glaring light on a strange horizon / Some hundred and fifty years ago,” the poet blurs the line between past and present, showing how the residue of colonial violence continues to shape the moral and ecological landscape of Odisha. The famine’s “insane light” is not simply historical; it irradiates the contemporary condition, suggesting a continuity of deprivation, alienation and moral decay. The second half of the poem shifts from collective memory to personal introspection:

“And what kind of life do I want to live today?

What dream should I dream?”

This transition aligns with New Historicism’s interest in how individuals internalise historical power structures. The speaker’s questions about peace and coexistence emerge from the debris of history, a consciousness scarred by inherited trauma. The ethical tension here, between living “in peace” and “getting along with others” in a fractured world, reflects the protagonist’s struggle for moral clarity amid systemic amnesia. Even if the sky has abandoned all its blue,” the poet’s voice insists on remembering as resistance. New Historicism reads ‘nature’ as a cultural construct that mirrors historical power relations. In Mahapatra’s imagery, the natural world, sun, sky, tree, and cloud bear witness to human suffering. The land becomes a colonised body:

“It’s body was fire, and its feet was ash.”

Here, Odisha is personified as both victim and witness. The bodily metaphors transform the abstract famine into visceral suffering, a poetics of embodied history. Nature, stripped of its transcendence, is part of the colonial machinery of devastation. Mahapatra’s English reimagining of an Odia tragedy, and Mishra’s subsequent translation, add layers to this historical recovery. Through translation, the pain of a region enters the global literary conscience. New Historicism would read this as a circulation of power and meaning; the local becomes legible to the global, yet risks being aestheticised or appropriated.

Mishra’s act of translation continues the ethical dialogue between representation and authenticity. How does one ‘translate’ a people’s suffering without erasing its specificity? In the New Historicist paradigm, “The Insane Light of the Odisha Famine of 1866” is both a literary and historical act, a rewriting of colonial modernity through the lens of indigenous pain. Mahapatra transforms archival silence into poetic voice, reclaiming Odisha’s history from imperial marginality. The ‘insane light’ becomes a metaphor for the moral frailty of both empire and modernity, a radiance that exposes the ethical failure of civilisation itself. Through the poem, Mahapatra performs what Stephen Greenblatt calls a poetics of subversion; he restores history’s lost bodies and voices by making poetry a site of memory, mourning, and moral reckoning.

Mahapatra’s works, such as “Hunger,” “Myth,” and “Summer”, are hailed as flawless examples of grand poetry that compel readers to grapple with profound societal truths (Bhardwaj and Gangwar 111). His engagement with Indianness and the themes that exhibit Indian ethos is a cornerstone of his poetic oeuvre, reflecting a profound exploration of cultural identity, regional specificity, and existential dilemmas (Thoughtful Critic 12). Mahapatra’s poetry serves to reveal socioeconomic facts, aiming to depict the true sociopolitical and sociocultural characteristics of its members (Gupta 78).

His poetry often portrays the complexities of contemporary Indian society, blending realism with philosophical insights to offer a deep understanding of the human condition (Bhardwaj and Gangwar 112). To carry these opinions of the critics further, a critical reading of Mahapatra’s rather obscure poetry is needed, though Mahapatra never accepted the fact that his poetry was complex and obscure for the common readers. An evocative yet complex poem, “Darkness”, has layers of ‘untranslatable’ ideas, which are translated by the deft hands of Mishra.

Today time dies inside its own dream

And in the centre of an unbelievable space Hangs a darkened earth

That once was bright and green,

Today too, my very dear, familiar Odisha Has entered the last days of her innocence

Brothers,

Whom should I implore

To do something to this darkness The charred wife’s burnt-coal eyes

The chopped off hand of a disobedient child

The unending sobs of this blood-soaked earth Where shall I carry them?

To which empty place of Odisha

Where hands burning silently inside hands Turn into fragrant petals

Should I carry them?

Where can I find an answer?

Mahapatra’s “Darkness”, in Mishra’s translation, is a lament for a dying homeland, it is also a deeply self-reflexive meditation on the crisis of meaning in the postcolonial modern situation. The poem transforms Odisha, once “bright and green”, into a synecdoche for the moral and cultural desolation of India’s collective conscience. Through an imagist economy of pain, “charred wife’s burnt-coal eyes,” “chopped off hand of a disobedient child”, Mahapatra exposes the violence inscribed in the body of the nation, where gendered and subaltern suffering becomes emblematic of a civilisation’s fall from grace. The poem’s darkness is both ontological and ethical, echoing Walter Benjamin’s idea that every document of civilisation is simultaneously a document of barbarism (Benjamin, On the Concept of History 55).

n translation, Mishra’s rendering performs a cultural translation that transposes Mahapatra’s Odia sensibility, the tactile immediacy of local suffering, the ritualised grief of Odisha’s soil, into an English idiom without erasing its rootedness. Yet, this act of translation itself underscores the epistemic gap between language and experience, the impossibility of fully transferring indigenous anguish into the colonizer’s tongue. The poet’s anguished question, “Where can I find an answer?”, resonates as an exclamation for ethical witnessing, where poetry becomes an archive of loss and resistance against the erasures of both history and translation.

In this context, I am particularly intrigued by a poem, “Life”:

It happened perhaps long ago

but I haven’t been able to forget even the year.

It was 1954, the year of

the first general election of Independent India.

In the dense forest of Sukinda, there we were,

in a broken-down lower primary school shed,

where a make-shift arrangement was made

for our three days’ stay and for the casting of votes.

Nothing of the voting comes to mind,

I only remember the dense forest where day sinks straight

into night without the hour of twilight,

and the city-life, left behind...

Mahapatra’s “Life”, as translated by Mishra, stages an intimate encounter between history and memory, locating the individual consciousness in the existential void of postcolonial India. The poem’s recollection of 1954, the year of the first general election, becomes less a historical moment of democratic awakening and more an existential meditation on alienation and absurdity in the Sartrean sense. The forest of Sukinda, where “day sinks straight into night without the hour of twilight,” symbolises an ontological in-betweenness, a liminal space where the boundaries between nature, history and self dissolve. This twilight-less forest resists the teleology of modernity, echoing Homi Bhabha’s idea of the ‘unhomely’ in postcolonial discourse, the intrusion of the nation’s grand narrative into the fragile interiority of lived experience. The speaker’s failure to remember the act of voting, supposedly the emblem of freedom, signifies a disjunction between political independence and existential meaning, reflecting Heidegger’s notion of ‘Geworfenheit’ (thrownness), the human subject cast into a world stripped of transcendental order. Mishra’s translation performs an act of cultural translation (Spivak), carrying Mahapatra’s rooted Odia sensibility, its arboreal silences, and its temporal circularity into English while retaining its metaphysical estrangement. The poem is not a celebration of India’s democratic past; it is a quiet rebellion against historical optimism, revealing how the self remains suspended between memory and nothingness, caught in the existential absurdity of life.

Mahapatra’s “A Poem on Untouchability” is nothing less than a site where translation enacts the fierceness it seeks to expose. The poem’s minimalism, its quiet, restrained diction, contradicts the profound ethical and ontological rupture it articulates, the persistence of caste impurity even beyond death.

It’s my appeal to you, dear friends –

That, on the day of my death do not come in your grief

to see me for the last time.

It pains me a lot

to think of that day

when, standing by my dead body, you’d be speaking to yourselves

that, as soon as you’d get back home,

you would wash your body clean, before you do anything else.

In the Odia original, Mahapatra’s tone carries a lived cultural anguish embedded in local idioms of ritual pollution and social segregation; in translation, that affective immediacy is filtered through what Walter Benjamin calls ‘the afterlife of the text.’(Benjamin, On the Concept of History 56) Mishra’s English rendering, while authentic in sense, inevitably transforms the bhava of embodied humiliation into a linguistic abstraction, thereby demonstrating the tension Gayatri Spivak describes in her essay “The Politics of Translation,” where subaltern speech risks being domesticated by the hegemonic language of the West. The poem’s stark instruction, “do not come in your grief / to see me for the last time”, unfolds as an existential resistance against both social hierarchy and the human desire for posthumous dignity, aligning with Camus’s absurd man who asserts meaning in the face of absurdity.

Translation becomes both a tool of survival and a site of loss; the English text memorialises a caste-marked consciousness while simultaneously revealing the impossibility of translating the abjection of untouchability into the universalist idiom of Western humanism. The poem stands as a radical critique of cultural translation, a reminder that some forms of suffering remain untranslatable, not because of linguistic limits, but because they are structurally silenced by history. Mahapatra’s “A Poem on Untouchability” is a deeply unsettling text that traverses the fault lines between postcolonial history, caste epistemology and the metaphysics of representation. The poem’s sparse, almost ascetic language is deceptive; it performs what Lyotard calls ‘the differend’, a moment where suffering resists articulation in the dominant discourse. In the post-post-modern framework, the poem dismantles Nehruvian modernity’s myth of a secular, egalitarian India by exposing the persistence of caste as a structuring principle of both body and memory. The speaker’s plea, “do not come in your grief to see me for the last time”, is not merely an act of dismissal; it is a subversive re-inscription of subjecthood, a reclaiming of agency from a society that denies it even in death. This gesture mirrors Derrida’s notion of ‘hauntology’, the persistence of a spectral injustice that refuses closure, haunting the moral imagination of the nation-state.

The poem’s self-reflexive awareness of ritual, purity and gaze/body politics dismantles the binaries of life and death, purity and pollution, self and the other. Mahapatra’s use of minimalist imagery opens a semiotic void, an aporia where meaning collapses under the weight of historical violence. The English translation by Mishra enacts what Homi Bhabha terms ‘cultural translation’, a process not of equivalence but of negotiation, where the subaltern experience of caste oppression is re-signified in a global linguistic economy. Yet, in this very act, the poem becomes a critique of Western universalism; its untranslatability exposes the limits of liberal humanist empathy.

The translated text, therefore, oscillates between presence and absence, retaining the ‘trace’ (Derrida) of the Odia original even as it gestures toward a transnational readership incapable of fully grasping its ethical gravity. “A Poem on Untouchability”, to me, as more of an English teacher/reader, inhabits the liminal space between voice and silence, history and erasure, a quintessentially postcolonial text that transforms the politics of touch into an epistemology of resistance.

The poem “Identity” is yet another stance of the epistemology of avant-garde poetry:

It has nothing to do with one’s birth.

After my death perhaps I’m with those who murdered me

And find that I am not alone.

All night

Through the solitary cell of Chaitra I think of that child

Who keeps looking for the scent

Of the funeral ground mango-blossoms

Who runs after a snake on the riverbanks

With a hope to find something new,

Until it slips into the water

And who, beneath the tender wings of sparrows

Finds the absence of free, unfettered moments

And keeps looking at his own being

Trapped in the dense roots of orders and rules

As he keeps looking down to them,

Are there ever words for identity?

“Identity”, translated into English by Mishra, is a meditation on the fractured, contingent nature of selfhood in the oppressive frameworks of culture, history and power. Reading through the lens of Cultural Studies, the poem destabilises essentialist notions of identity by exposing how it is produced through ideology, social order and institutional discipline rather than innate essence. The speaker’s ironic recognition, “It has nothing to do with one’s birth”, invokes Stuart Hall’s idea of identity as a “production, always in process”, historically and discursively constituted rather than naturally given. The imagery of the “funeral ground mango-blossoms” and the “snake slipping into water” becomes an allegory of loss, displacement and the perpetual deferral of meaning, what Hall calls the ‘diasporic consciousness’ (Stuart Hall 77) of existence. Mahapatra’s ‘child’ becomes a cultural subject trapped “in the dense roots of orders and rules,” echoing Althusser’s theory of interpellation– the moment when the individual is “hailed” into subjecthood by ideology and thus alienated from authentic being. Mishra’s translation intensifies this alienation by transposing Mahapatra’s Odia idioms rooted in ritual, nature, and affect into the abstract register of English modernism, enacting the cultural dislocation the poem thematises. The final question, “Are there ever words for identity?”, functions as both epistemological and political critique: it gestures toward the impossibility of naming the self in the grammar of domination, where language becomes complicit in erasure. The poem transforms the search for identity into a postcolonial allegory of silence, exile, and the untranslatable self, as it is in yet another poem, “That Which Is Left Behind”:

A little of everything is always left behind

From the burden on our shoulders...

Like heaps of salt on the Chilika shores.

When a mother also tells her child a story

Something of that remains:

A bit of fear A bit of hope

And her reflection as she runs about breathless In her own mirror--

As if it were the journey of some person

Quietly approaching the edge of earth’s golden horizon.

Yes, always something of those stories

Is left behind

Like the two banks of a river when the flood subsides

Or the feeling of repose

After one climbs the twenty-two steps Or the lonesome breeze that stays on

After the funeral is over in the burning ground. But who can say

What remained of the sound of the pistol

After Mahatma Gandhi had been shot dead?

Perhaps something was, something small,

Only in those lawns, upon that unknown grass,

Trampled under boots for ages afterward.

After each happening, something, A little of it remains,

A blood stain,

A shard of broken bangles

A tear drop from a betrayal in the bottle of

Phalidol

And in all those lie

The noose of helpless memories.

The poem is an intricate meditation on the residues of history and the metaphysics of remembrance, an elegy not exactly for individuals or events but rather for the very condition of memory as a culture. The poem participates in the act of the past, which Astrid Erll calls ‘Mnemoculture’, the collective practices through which societies remember, forget, appropriate and narrativise the past, by transforming private recollection into a cultural archive of loss. Mahapatra’s recurring imagery of remnants, “heaps of salt on the Chilika shores,” “a blood stain,” “a shard of broken bangles”, function as mnemonic markers, embodying what Marianne Hirsch terms ‘Postmemory’, the haunting persistence of trauma transmitted across generations.

The poet’s consciousness of death is visible throughout his oeuvre and becomes inseparable from his awareness of cultural mortality, the fading of stories, rituals and moral certainties in the wake of violence and modernity. The invocation of Gandhi’s assassination, “What remained of the sound of the pistol…”, signals the collapse of transcendence into memory’s material residue, where sound, like ethics, dissolves into silence. Mishra’s translation extends this phenomenology of loss by translating language as well as ‘affect’, performing what Ricoeur might describe as the hermeneutics of memory, the act of interpreting the past through linguistic fragility. In this process, the poem evolves into a postcolonial palimpsest, where traces of the local, Chilika, the funeral ground, the maternal story, intermingle with the global ethics of remembering atrocity. Ultimately, Mahapatra’s verse suggests that memory is an afterlife, a liminal state between being and oblivion, where the poet’s death consciousness merges with a collective mourning for a civilisation that can only survive through its fragments.

Mishra carefully chooses a very small/short story of Mahapatra in the poem “A Small Story” to translate, where the poetic effect is nuanced with the poet’s use of his own name:

Jayanta Mahapatra has not been able

To part from his body and from his soul

His grandfather’s blood was his, too

He kept himself hidden in his grandfather’s dreams.

Today, he is not alone

He has become a memory himself,

Of the deep emptiness of time:

Inside time his ancestors

Silently draw lines on earth

And

Outside the cage of his knowledge

The quiet, secret life of his grandfather

Keeps floating in his ignorant body.

The poem is a haunting enactment of ancestral memory and embodied history, where the poet’s self becomes a site of intergenerational haunting. The poem performs, like Jacques Derrida calls ‘hauntology’, a spectral return of the past that refuses to die, revealing how the personae lives in the ghostly continuum of inherited violence and silence. Mahapatra’s identification with his grandfather’s blood inscribes the intimate politics of lineage, memory and guilt, transforming the self into a palimpsest of trauma. The poet’s “ignorant body” becomes a living archive, which makes me think of corporeality and body politics, echoing Michel Foucault’s idea of ‘biopower’, where the body is both the vessel and victim of historical inscriptions. In this framework, the poem’s invocation of ‘time’ as emptiness resonates with Heidegger’s ‘Sein-zum-Tode’ (Being-toward-death), a consciousness of finitude that shapes Mahapatra’s recurring poetics of mortality. From the perspective of translation theory, Mishra’s English version performs a delicate negotiation between the Odia original’s cultural intimacy and the universal abstraction of English modernist idiom. This process embodies what Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak terms the ‘politics of translation’, a tension between fidelity to the subaltern texture of the source language and the demand for legibility in the target language.

The Odia nuances of kinship, ritual memory, and ancestral belonging are inevitably “foreignised” or muted in English, enacting Lawrence Venuti’s idea of ‘domestication’ as a subtle act of erasure. Yet, this very loss is productive; it mirrors the poem’s theme of absence and spectral inheritance, where what is “left behind” becomes the truth of identity. “A Small Story” transcends its biographical frame to become a philosophical allegory of being, the poet as a haunted self, speaking in translation from the ruins of history, where language becomes both the wound and the witness. His work is deeply informed by his bilingual identity—an Odia poet writing in English—which allows him to navigate the complexities of postcolonial India while asserting a distinct cultural voice (Thoughtful Critic 14).

On a different note, who, except Mishra, could have understood and chosen the satire and dark humour of Mahapatra, which he sometimes uses in poetry! In the poem, “The Land of the Magic Cap”, Mahapatra writes,

This country

Suits me quite well.

With eyes downcast

If you accept the punishment that comes to you,

Life moves the right way

Somehow, always,

These shoulders feel burdened, heavy, As though I were

Carrying on my shoulders My country’s bier.

And if I, perchance,Put on a Khadi Cap on my head,

Those million starving eyes

Gleaming in democracy’s tears

Suddenly disappear somewhere.

This country of mine Really suits me a lot.

Mahapatra’s “The Land of the Magic Cap” is a biting political allegory that fuses irony, despair and moral indictment to expose the hollow theatre of democracy. The poem’s satirical undertone, its mock affirmation that “this country suits me quite well”, operates in the register of what Mikhail Bakhtin calls ‘double-voiced discourse’, where irony destabilises official narratives of a democracy. Mahapatra’s subdued diction masks a profound rage against the complicity of silence and the normalisation of suffering; his ‘Khadi Cap’ becomes a metonym for nationalist hypocrisy, echoing Homi Bhabha’s notion of mimicry as “almost the same but not quite”, a repetition of colonial authority in the disguise of freedom. Mishra’s translation succeeds in carrying this irony across linguistic borders by preserving Mahapatra’s tonal restraint, allowing English to echo the Odia original’s quiet sarcasm, rather than mimicry, than overstate it. Mahapatra’s use of imagery and symbols is another aspect of his craftsmanship, with his poetic style being highly symbolical and imagistic (Hazarika 14).

Through strategic literalism and rhythmic containment, Mishra renders the satire legible to global readers without erasing its rootedness in India’s moral-political disillusionment. The line “Those million starving eyes / Gleaming in democracy’s tears” encapsulates the poem’s Foucauldian critique of power, how the state disciplines visibility and invisibility, rendering suffering into spectacle. Thus, the translated poem becomes both an act of linguistic fidelity and political continuity, where Mahapatra’s ethical irony survives in Mishra’s version as a subdued but potent form of resistance, a nation elegised through its own performative self-congratulation.

Mahapatra’s exploration of Indianness is deeply tied to his engagement with Odisha’s cultural and spiritual heritage, using symbols like the Jagannath Temple and the Mahanadi River to reflect on broader existential and socio-political themes (Thoughtful Critic 18). The engagement with Jayanta Mahapatra’s poetics through the mediatory lens of Gopa Ranjan Mishra’s translations foregrounds the epistemic intricacies inherent in the act of cultural and linguistic transference. Mishra’s translational theory and praxis do not exactly reproduce Mahapatra’s verbal economy; Mishra engages with and operates with a critical apparatus that negotiates the interstitial space between source and target cultures, revealing the liminality of meaning and the inherent instability of textual signifiers. When situated in the critical pedagogy of translation, this intermediation exposes the dialectical tension between fidelity and interpretive creativity, foregrounding translation as an ethical, cognitive and aesthetic encounter rather than a reductive technical procedure.

The transposition of Mahapatra’s existential meditations on memory, absence and corporeal temporality through translation pedagogy into Anglophone registers illuminates the porous boundaries of literary consciousness, challenging monolithic narratives of Indian writing in English while interrogating the hegemonies of Western literary theories. The translational encounter is a site of epistemic pluralism; it embodies the intertextual negotiations between tradition and modernity, locality and universality, presence and erasure, reconceptualising the poet’s oeuvre as a dynamic locus. In the deft hands of Mishra, the ontologies of language, culture and memory converge, create and re-create.

Works Cited

1. Hazarika, P. “Poetic Craft in Jayanta Mahapatra’s Poetry.” RGU Journal of Social Science and Research, vol. 1, no. 1, Jan. 2025, pp. 14–17.

2. Bhardwaj, Purnima, and Dilkesh Gangwar. “Jayanta Mahapatra’s Imaginative Realism and Philosophic Insights in Indian Social Milieu.” International Journal of English Literature and Social Science, vol. 9, no. 2, Mar.–Apr. 2024, pp. 1–5.

3. “Themes of Indianness in the Poetry of Jayanta Mahapatra.” Thoughtful Critic, 13 Feb. 2025, thoughtfulcritic.com/features/poets/themes-of-indianness-in-the-poetry-of-jayanta-mahapatra-an-analysis/.

4. Gupta, A. K. “Navigating Social Realism in the Poems of Jayanta Mahapatra.” Dialogue: A Journal of English Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 2023, pp. 45–50.

5. Mahapatra, Jayanta. A Rain of Rites. University of Georgia Press, 1976.

6. Mahapatra, Jayanta. “Hunger.” A Rain of Rites, University of Georgia Press, 1976, pp. 56–57.

7. Mahapatra, Jayanta. Collected Poems. Paperwall Publishing, 2017.

8. Mahapatra, Jayanta. “The Temple Road, Puri.” Collected Poems, Paperwall Publishing, 2017, p. 102.

9. Mahapatra, Jayanta. “Dawn at Puri.” Collected Poems, Paperwall Publishing, 2017, p. 103.

10. Mahapatra, Jayanta. “The Whorehouse in a Calcutta Street.” Poetry Magazine, vol. 153, no. 4, Nov. 1988, pp. 220–221.

11. Bassnett, Susan. Translation Studies. 4th ed., Routledge, 2014.

12. Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator.” Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn, edited by Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, 1969, pp. 69–82.

13. Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. Routledge, 1994.

14. Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass, University of Chicago Press, 1978.

15. Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory: An Introduction. 2nd ed., Blackwell, 1996.

16. Hall, Stuart. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, edited by Jonathan Rutherford, Lawrence & Wishart, 1990, pp. 222–237.

17. Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, Harper & Row, 1962.

18. Mahapatra, Jayanta. Collected Poems. HarperCollins, 2016.

19. —. Relationship. Chandrabhaga, 1980.

20. —. “Translating Silence: The Poetic World of Jayanta Mahapatra.” Indian Literature, vol. 67, no. 1, 2023, pp. 142–158.

21. Niranjana, Tejaswini. Siting Translation: History, Post-Structuralism, and the Colonial Context. University of California Press, 1992.

22. Ricoeur, Paul. Memory, History, Forgetting. Translated by Kathleen Blamey and David Pellauer, University of Chicago Press, 2004.

23. Sahu, Nandini. Recollection as Redemption. Authorspress, 2012.

24. Sahu, Nandini. Re-Reading Jayanta Mahapatra. Black Eagle Books, USA, 2024.

25. Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. Vintage, 1994.

26. Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism Is a Humanism. Translated by Carol Macomber, Yale University Press, 2007.

27. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “The Politics of Translation.” Outside in the Teaching Machine, Routledge, 1993, pp. 179–200.

28. Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ wa. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Heinemann, 1986.

29. Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2008.

30. Williams, Raymond. Culture and Society: 1780–1950. Columbia University Press, 1983.

- Benjamin, Walter. The Task of the Translator. 1923.

(https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/CONCEPT2.html)

- Benjamin, Walter. On the Concept of History, 1923.

(https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/books/Concept_History_Benjamin.pdf)

- Berman, Antoine. The Experience of the Foreign: Culture and Translation in Romantic Germany. SUNY Press, 1992.

34. Jenny Sharpe. Thinking “Diaspora” with Stuart Hall, Qui Parle, Vol. 27, No. 1 (JUNE 2018), pp. 21-46, Duke University Press

- Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. Routledge, 1994.

- Lefevere, André. Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. Routledge, 1992.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “The Politics of Translation.” In Outside in the Teaching Machine. Routledge, 1993.

- Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. Routledge, 1995.

- Mahapatra, Jayanta. Baya Raja and Bhitara Ghara (Odia).

Notes:

Mishra, Gopa Ranjan. (English Translations of Jayanta Mahapatra’s Odia Poetry).

All the quotes, text messages and the translations of Jayanta Mahapatra’s poetry from Odia to English have been collected from various emails and text messages that Mishra sent Nandini Sahu on various occasions. The translated poems of Mishra were published in many books and journals at a later stage, which have not been referred to in this article, as the quotations have been taken directly from Mishra, pre-publication.

Jayanta Mahapatra, Gopa Ranjan Mishra and Nandini Sahu shared a rare rapport that inspired Sahu to write this research paper, apart from her deep admiration for Mahapatra and Mishra as poets and scholars.

Photographs from Different Truths Archives

By

By

By

By

By

By