We are introducing a new column by Monika on DifferentTruths.com. Here we unveil lost arts of Jammu & Kashmir as vital historical documents, probing why they vanished.

AI Summary

- Introduces a new column by Monika on DifferentTruths.com, reframing lost arts of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) as “historical documents” shaped by disrupted social rituals.

- Explores vanished forms like Sharada script, temple murals, pre-Sufi music, and Bhand Pather through structural inquiry, not nostalgia.

- Treats loss as an archive, highlighting transmission breakdowns over centuries of upheaval.

Opening Manifesto: On the Study of Lost Arts

The study of art history in India has been largely shaped by survival. What remains is catalogued, conserved, and celebrated, while what disappears is often treated as cultural failure or historical inconvenience. This approach leaves a significant absence unexamined: art forms that vanished not because they lacked value, but because the social, ritual, and pedagogical conditions that sustained them were disrupted.

Lost arts are not aesthetic failures. They are historical documents.

To study lost art forms is to study interruption… of community life, of ritual time, of apprenticeship, and of intergenerational transmission. It requires shifting attention away from nostalgia and toward structural inquiry: what conditions allow an art to live, and what conditions cause it to withdraw?

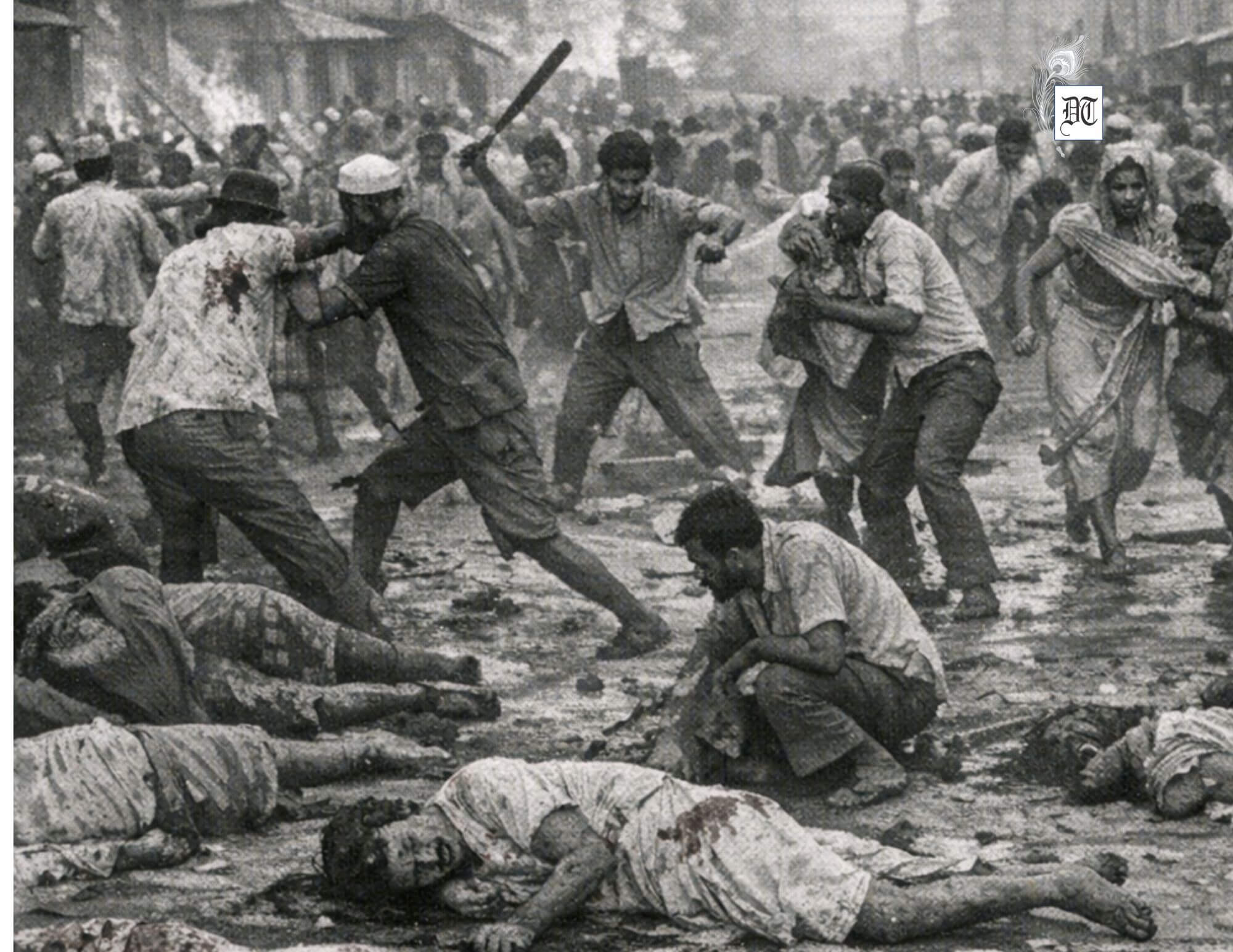

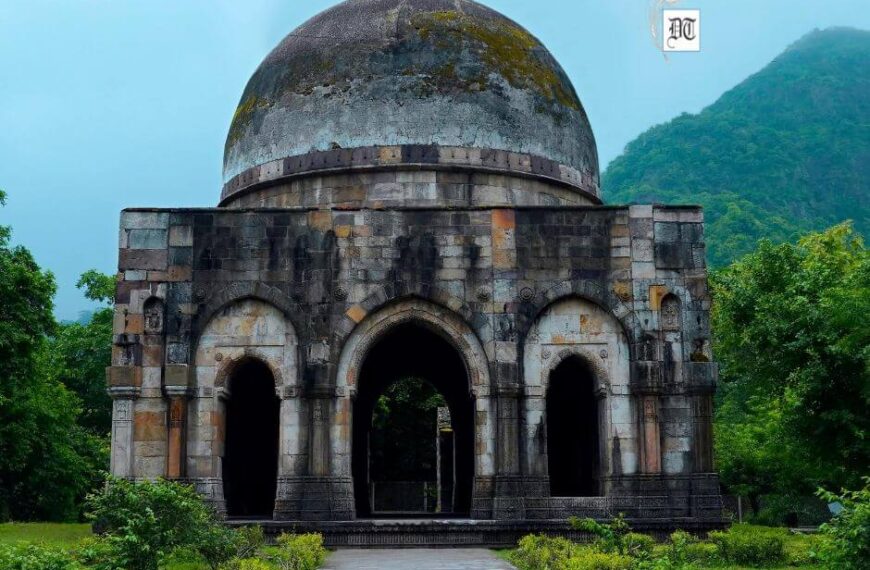

Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) offers a critical point of departure for such a study. Its geography, philosophical density, and repeated historical ruptures make it one of the most instructive regions for understanding how complex artistic ecosystems disappear without formal extinction.

This essay approaches the lost arts of Jammu & Kashmir as cultural systems, not isolated techniques, and treats loss itself as an archive,

Kashmir as a Cultural Palimpsest

Situated at the intersection of South Asia, Central Asia, and the trans-Himalayan world, Jammu & Kashmir historically sustained layered artistic traditions shaped by Shaiva philosophy, Buddhist pedagogy, courtly practice, and vernacular life. Artistic production in the region was rarely autonomous; it was embedded within ritual calendars, domestic instruction, oral discourse, and seasonal rhythms.

The disappearance of many Kashmiri art forms did not occur through singular acts of destruction. Instead, these forms thinned over centuries through political upheaval, climate vulnerability, shifts in patronage, displacement, and the gradual breakdown of community-based transmission.

What survives today are fragments: texts without teachers, scripts without scribes, performances without philosophical depth. These fragments allow for academic inquiry precisely because they point toward what is no longer present.

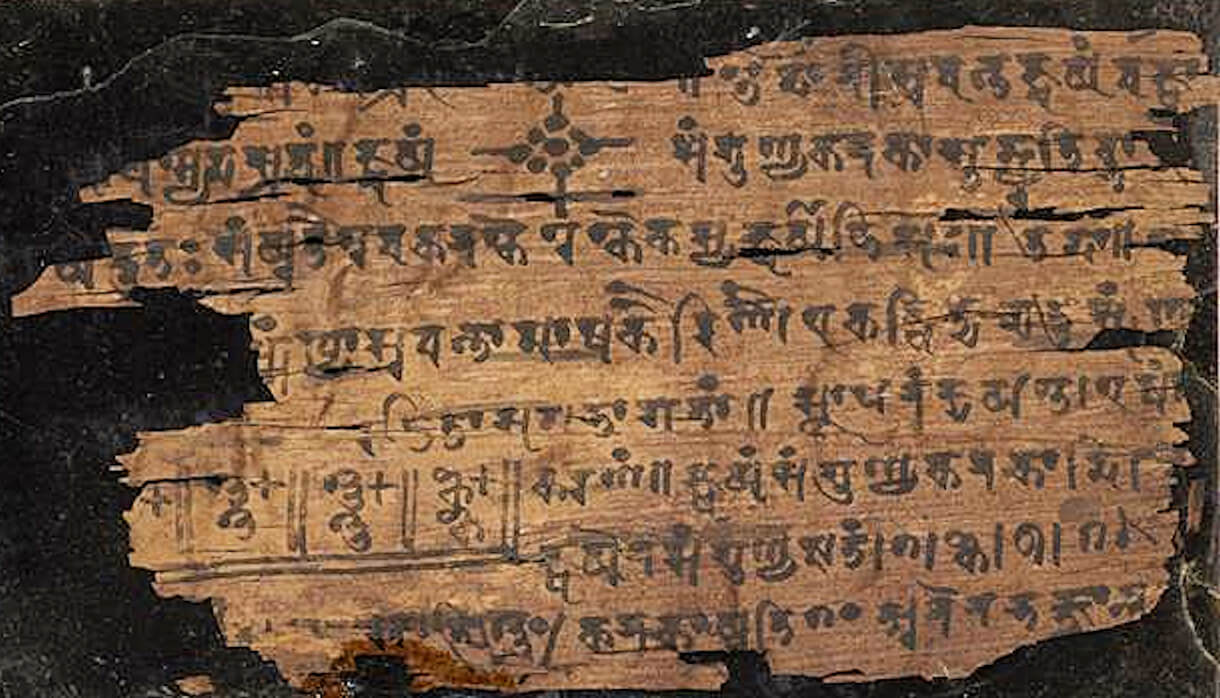

Sharada Script – From Writing System to Artistic Discipline

Sharada is commonly classified as an ancient script of Kashmir. Such a classification reduces a once-living artistic discipline to a linguistic artefact.

Historically, Sharada functioned as a composite art form. Manuscript layout followed strict proportional systems. Calligraphic modulation conveyed semantic and philosophical emphasis. Marginal annotations, symbols, and spatial hierarchies formed a visual language parallel to the written word.

Manuscript production involved specialised knowledge: preparation of writing surfaces, formulation of inks, and ritual protocols governing copying and preservation. These practices were transmitted through apprenticeship rather than formal institutions.

While Sharada survives today through epigraphic study and academic reconstruction, its aesthetic grammar and pedagogical lineage have been severed.

Status: Functionally extinct as a living art form; survives only as deciphered script.

Temple Murals and Painted Wooden Architecture

Kashmir’s architectural traditions relied extensively on wood, shaped by climate and seismic conditions. Sacred spaces – temples, monasteries, and shrines – were often internally painted or carved.

Historical and archaeological evidence suggests narrative mural sequences rather than singular iconic images, synthesising Shaiva, Buddhist, and local cosmologies. Mineral pigments adapted to cold and moisture were commonly used.

Wooden architecture, however, is inherently vulnerable. Repeated cycles of decay, reconstruction, iconoclastic episodes, and neglect resulted in the near-total loss of painted interiors. Archaeology offers only partial confirmation; technique, composition, and iconographic conventions remain unrecoverable.

Status: Largely lost.

Pre-Sufi Musical Systems of Kashmir

Before Persianate and Central Asian influence reshaped the region’s soundscape, Kashmir sustained a musical system closely aligned with ritual practice and Shaiva philosophy.

Textual references indicate modal structures distinct from contemporary Hindustani ragas, instruments no longer identifiable in material culture, and performance contexts tied to seasonal observance and contemplative practice.

No continuous oral lineage survives. Later musical traditions represent cultural layering rather than evolution. The original system ceased to exist when its ritual and philosophical contexts dissolved.

Status: Lost; preserved only through indirect textual memory.

Bhand Pather: From Philosophical Satire to Folk Performance

Bhand Pather is often cited as Kashmir’s traditional folk theatre. This designation obscures the complexity of its earlier forms.

Historically, performances combined satire, verse, music, and social critique. The Bhand occupied a liminal role… artist, commentator, and social interlocutor. Scripts were fluid, evolving through oral transmission rather than fixed authorship.

Contemporary performances retain structural elements but often lack the philosophical density and political audacity documented in earlier accounts.

Status: Partially lost; structural form survives, intellectual depth diminished.

Ritual Use of Textiles Without an Autonomous Art Tradition

Unlike several other Indian regions, Jammu & Kashmir does not present evidence of a distinct, named ritual textile art tradition with specialised techniques or symbolic grammars.

Nevertheless, textual sources indicate the ritual use of cloth (vastra) in temple practice, seasonal observance, and domestic rites.

References in early Kashmiri texts suggest that textiles functioned as ritual instruments rather than artistic objects. Ordinary local weaves, primarily wool and silk, were employed for covering sacred spaces, marking temporal transitions, and facilitating ceremonial acts. Their value lay not in craftsmanship or permanence, but in contextual correctness.

The loss here is therefore not of a recognisable textile art form, but of the ritual ecosystems that activated textiles as meaningful objects. Once these ecosystems eroded through displacement, altered patronage, and shifts in social structure, textile usage reverted entirely to utilitarian and commercial domains.

The absence of surviving specimens, detailed descriptions, or technical manuals supports this interpretation. In Kashmir, ritual textiles did not disappear as art; they withdrew as practice.

Status: Contextually lost rather than materially extinct.

Oral Philosophical Pedagogy

Kashmir Shaivism is now primarily encountered through texts. Historically, it was transmitted through dialogue, parable, and domestic instruction.

Knowledge transmission relied on intergenerational continuity, informal teaching environments, and the integration of philosophy into daily life. Displacement and social fragmentation disrupted this mode of learning. Texts survived; pedagogical practice did not.

Status: No longer transmitted through living practice; survives only in textual form

Seasonal Ritual Performance and Embodied Time

Many Kashmiri art forms were inseparable from seasonal cycles—harvests, snowfall, river thaw, and solstices. Performance functioned as a response to time rather than spectacle.

Modern detachment from seasonal living rendered these practices obsolete. Calendar references remain; embodied performance does not.

Status: Fragmented; largely lost.

Endnote: Loss as Methodological Evidence

The lost arts of Jammu & Kashmir demonstrate that artistic vitality depends less on objects than on conditions of transmission. When community continuity fractures, art withdraws quietly.

Studying these losses shifts art history from celebration to inquiry. Absence itself records historical pressure, displacement, and cultural exhaustion.

References:

1. Kalhaṇa, Rājataraṅgiṇī, trans. M. A. Stein, London, 1900.

2. M. A. Stein, Ancient Geography of Kashmir, Royal Asiatic Society, 1899.

3. Nilamata Purāṇa, ed. Ved Kumari Ghai, J&K Academy of Art, Culture and Languages, 1967.

4. Mark S. G. Dyczkowski, The Doctrine of Vibration, SUNY Press, 1987.

5. B. N. Pandit, Specific Principles of Kashmir Shaivism, Munshiram Manoharlal, 1997.

6. J. L. Kaul, Kashmir Through the Ages, Capital Publishing House, 1997.

7. Ishaq Khan, Kashmir’s Transition to Islam, Manohar, 1994.

8. Bharat Dogra, “Bhand Pather: Traditional Folk Theatre of Kashmir,” Indian Folklife.

9. John Siudmak, “The Śāradā Script of Kashmir,” Indo-Iranian Journal, 1989.

10. Finbarr Barry Flood, Objects of Translation, Princeton University Press, 2009.

11. UNESCO, Intangible Cultural Heritage and Safeguarding Practices.

Suggested Online Resources:

1. J&K Academy of Art, Culture and Languages: https://jakacl.jk.gov.in

2. National Mission for Manuscripts: https://www.namami.gov.in

3. IGNCA: https://ignca.gov.in

4. British Library Kashmiri Manuscripts Collection: https://www.bl.uk

Visuals sourced by the author from Google.

By

By

By

By