Akash explores Aurangzeb’s time, India’s controversial Mughal emperor, and states how his devout Islamic faith shaped his powerful reign, exclusively for Different Truths.

Aurangzeb Alamgir, born as Muhi al-Din Muhammad on 3 November 1618, was the sixth and last widely recognised powerful Mughal emperor of India, reigning from 1658 until he died in 1707. His reign marked the Mughal Empire’s greatest territorial expansion and simultaneously sowed the seeds for its eventual decline. One of the most controversial figures in Indian history, Aurangzeb is remembered both as a devout Sunni Muslim ruler and as an emperor whose religious policies have inspired admiration and condemnation in equal measure.

This article explores Aurangzeb’s relationship with Islam, examining how his religious convictions shaped his governance, legal reforms, taxation, architecture, administrative actions, treatment of non-Muslims, and relations with Muslim sects.

Early Life and Islamic Orientation

Born into the Timurid dynasty, Aurangzeb was raised in a highly Persianised and Islamic imperial court. His father, Shah Jahan, and his predecessors had generally embraced a syncretic culture combining Islamic and Indian elements. However, Aurangzeb diverged sharply from this tradition. He was educated in Islamic theology, Arabic, Persian, and military arts, and he memorised the entire Quran. Fluent in Persian and Chagatai Turkic, he also mastered Hadith literature and Islamic jurisprudence, laying the foundation for his orthodox Muslim worldview.

He was notably influenced by the Mujaddidi Order and a disciple of the son of Ahmad Sirhindi, a leading figure in reviving Islamic orthodoxy in India. His religious conservatism, however, was not merely personal; it fundamentally informed his imperial policy.

Ascension to the Throne and Justification through Islam

Aurangzeb’s rise to power was marked by fratricidal conflict. Despite the absence of primogeniture in Mughal succession, Aurangzeb justified his military campaigns against his brothers Dara Shikoh, Murad Baksh, and Shah Shuja as necessary to uphold Islamic orthodoxy. He accused Dara of apostasy and claimed to restore a “true Islamic” rule, a rationale he used to legitimise his coronation and the execution of Dara.

His accession was initially met with resistance from religious scholars. The chief Qazi refused to crown him because of his actions against his father and brothers, prompting Aurangzeb to publicly adopt the image of a “defender of the sharia.” This image would persist and define his political persona.

Religious Reforms: The Fatawa-e-Alamgiri

One of Aurangzeb’s most lasting legacies in the Islamic world was the codification of Islamic law into the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri. This compendium of Hanafi jurisprudence, compiled by hundreds of Islamic jurists under his patronage, became a foundational legal text in many Islamic courts.

Unlike his predecessors, who balanced Islamic and secular laws (zawabit), Aurangzeb emphasised the superiority of the Sharia. Yet, contradictions emerged when he allowed secular regulations to supersede religious ones when politically expedient. Still, his pursuit of an Islamic legal framework marked a significant turning point in the Mughal Empire’s judicial history.

Suppression of Practices Contrary to Islam

Aurangzeb actively sought to purify Mughal society of what he perceived as un-Islamic practices. In 1663, he issued a decree banning the practice of sati (the burning of widows), which he condemned on Islamic ethical grounds. Despite widespread evasion through bribery, contemporary accounts noted that the practice diminished during his reign.

He also banned the celebration of Nauroz (a Persian New Year festival), prohibited music at court, and discouraged artistic expressions that conflicted with Islamic sensibilities, although these bans were not always strictly enforced. Notably, historian Katherine Brown challenges the extent of these bans, suggesting that cultural austerity may have stemmed from financial constraints as much as religious zeal.

Treatment of Non-Muslims: Between Orthodoxy and Pragmatism

Aurangzeb’s policies toward non-Muslims, particularly Hindus and Sikhs, are among the most debated aspects of his reign. He re-imposed the jizya (a poll tax on non-Muslims) in 1679 after a hiatus of over a century. Though the tax had socio-political dimensions, including revenue generation during prolonged military campaigns, it was interpreted as a religiously discriminatory policy. Women, children, the poor, and Brahmins were exempt, but the act stirred resentment.

Temple destructions, such as the Vishvanath Temple in Varanasi and the Kesava Deo temple in Mathura, were sanctioned under his rule. While colonial and nationalist historians often cited these as acts of Islamic iconoclasm, modern historians argue they were politically motivated, aimed at suppressing rebellion or asserting imperial authority.

Simultaneously, Aurangzeb issued land grants to Hindu temples and shrines. He funded the Mahakaleshwar Temple in Ujjain, the Balaji Temple of Chitrakoot, and the Shatrunjaya Jain temples. He also maintained dargahs and gurudwaras, indicating a more complex and layered relationship with India’s religious diversity.

Executions and Persecutions: Enforcing Orthodoxy

Aurangzeb’s rule saw the execution of several prominent religious figures who diverged from orthodox Sunni Islam. The most notable were:

- Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh Guru, was executed in 1675 for defying imperial orders, possibly resisting forced conversions.

- Sarmad Kashani, a Sufi mystic and poet of Jewish origin, was executed for heresy and public recitation of unorthodox beliefs.

- Sambhaji, the Maratha king, was tried and executed for atrocities against Muslims in Berar and Burhanpur.

- Syedna Qutubuddin, the 32nd Da’i al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra sect, was executed for heresy in 1648.

These executions reflect Aurangzeb’s efforts to enforce Sunni orthodoxy and control religious heterodoxy within the empire.

Administrative and Economic Policies Anchored in Islam

Aurangzeb introduced tax reforms inspired by Islamic injunctions. He eliminated over 80 taxes upon ascending the throne, arguing that they were un-Islamic. However, financial strains from prolonged military campaigns, especially in the Deccan, forced him to raise land revenue and reintroduce discriminatory taxation.

His economic policies also discriminated between Hindu and Muslim merchants, taxing the former at a higher rate (5%) than the latter (2.5%). Some scholars suggest these policies were designed to reinforce Islamic supremacy, while others see them as revenue-maximising measures in a context of imperial overstretch.

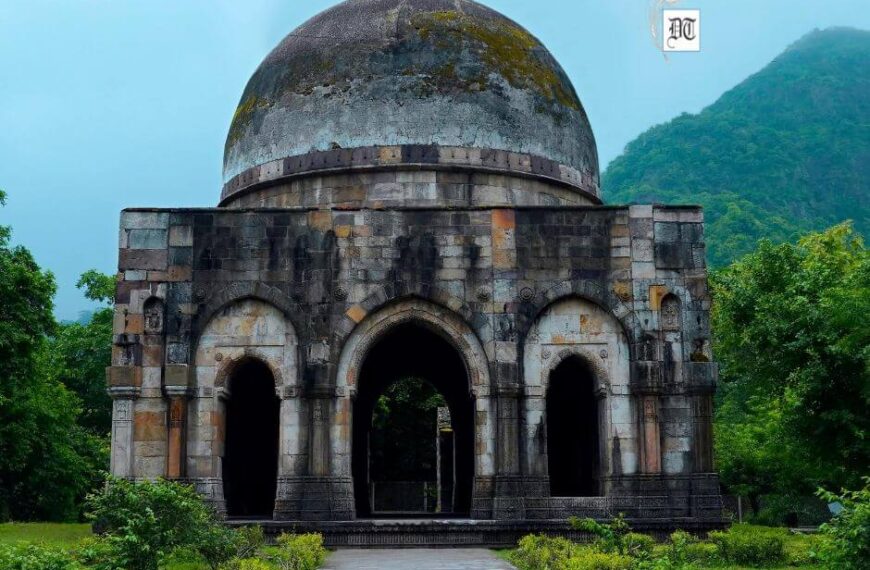

Islamic Architecture and Calligraphy

Aurangzeb diverged from the grand Mughal architectural tradition marked by the Taj Mahal. He preferred modest constructions, aligning with Islamic austerity. However, he commissioned significant Islamic structures, such as:

- Moti Masjid (Delhi) – a small white marble mosque for personal use.

- Badshahi Mosque (Lahore) – among the largest mosques in South Asia.

- Mosque in Srinagar – the largest in Kashmir.

His architectural period has been described as a phase of “Islamization” of Mughal architecture. He also undertook extensive restoration of existing mosques and religious tombs, and patronised Islamic calligraphy, producing handwritten Qurans in the elegant naskh script.

Cultural and Artistic Shifts

In contrast to Akbar and Jahangir, who promoted music and visual arts, Aurangzeb disapproved of them, considering them un-Islamic. Court musicians lost patronage, and miniature painting declined. However, he contributed to the expansion of Islamic art forms like calligraphy and Quranic transcription.

The textile industry thrived under his rule, with artisans producing fine muslins, brocades, and shawls, especially Pashmina and Kalamkari works, reflecting Persian artistic influence. François Bernier noted the sophistication of Mughal textiles, which reached Europe through trade.

Foreign Policy and the Islamic World

Aurangzeb maintained strong relations with the Islamic world, especially the Sharif of Mecca. He sent multiple missions bearing gifts and zakat to Mecca and Medina. However, by 1694, he grew disillusioned with the Sharif’s greed and ceased his donations.

Aurangzeb also supported Muslim rulers in Southeast Asia, notably the Aceh Sultanate, and exchanged gifts, including elephants. He warned the Dutch against interfering with Mughal-Aceh trade, showing his commitment to Islamic solidarity across regions.

Religious Pluralism in Bureaucracy

Despite his orthodoxy, Aurangzeb employed a considerable number of Hindus in his administration, more than his predecessors. By the end of his reign, 31.6% of imperial officers were Hindus, mostly Marathas. This reflects a pragmatic approach, where statecraft at times superseded religious bias.

However, he also encouraged high-ranking Hindu officials to convert to Islam and sought to reduce the number of non-Muslim nobles in court. This duality encapsulates his broader governance, firmly Islamic but occasionally flexible.

Legacy and Historical Debate

Aurangzeb’s legacy is deeply contested. Some historians portray him as a tyrant who dismantled India’s composite culture, while others highlight his administrative reforms, military prowess, and personal piety.

Katherine Brown argues that his name evokes images of religious bigotry, often divorced from historical facts. Richard Eaton estimates that only 15 temples were verifiably destroyed during his rule, a stark contrast to exaggerated claims. Others emphasise that his temple destructions often had political motivations tied to rebellion and not theology.

Conclusion

Aurangzeb’s relationship with Islam was multifaceted. He was not just a ruler who happened to be Muslim; he was a Muslim ruler who aimed to govern by Islamic principles. Yet, the demands of empire often compelled him to act pragmatically, at odds with his religious ideals. His reign saw a simultaneous assertion of Islamic orthodoxy and the pragmatic inclusion of non-Muslims in governance.

Ultimately, Aurangzeb remains a complex figure: a deeply pious ruler whose policies shaped and strained the fabric of Mughal India. His vision of an Islamic state was neither fully realised nor wholly rejected by his contemporaries, leaving behind a legacy that continues to provoke debate, admiration, and critique in equal measure.

References

- 1. Richards, John F. The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- 2. Metcalf, Barbara D., and Thomas R. Metcalf. A Concise History of Modern India. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- 3. Chandra, Satish. Medieval India: From Sultanate to the Mughals, Volume II. Har-Ananad Publications, 2005.

- 4. Ikram, S. M. Muslim Civilisation in India. Columbia University Press, 1962.

- 5. Asher, Catherine B. Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- 6. Gaborieau, Marc. Islam in South Asia: A Short History, Brill, 2009.

- 7. Alam, Muzaffar, and Sanjay Subhramanyam. The Mughal State, 1526-1750. Oxford University Press.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

Authentic😌💗💗✨✨ great article💖💖💖💖

Brilliant article son. It was Shamvaji Maharaj who tormented him to hell….