Prof Bhaskar elucidates that Indianisation embodies India’s diverse cultural ethos, blending ancient traditions, non-violence, and universal ethics amidst complex historical and modern dynamics, exclusively for Different Truths.

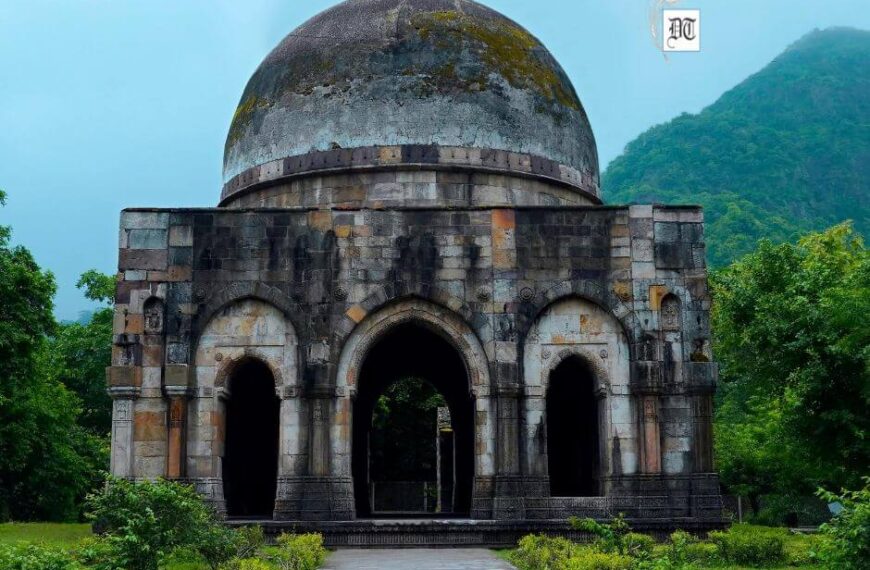

As one of the oldest civilisations and a country based on diversified languages-religion-culture and associated food habits and dress code across age and gender, it becomes difficult to pinpoint what Indianisation really means. This becomes more complicated if seen inter-temporally by sections of people in society that are not homogeneous. For the past five centuries, particularly since 1757, India has adopted the culture of British European countries; yet it seems too simplified a version of India’s cultural history. Even today, many of the parables that people in villages understand and keep reciting or practice are oral traditions, determined like the patt (religious reading) of Ramcharitmanas in the Heartland. Thus, it needs clinical understanding.

Violent or Non-violent?

India is associated with Gandhi-Buddha-Chaitanya, among others, who preached non-violence in human practices that included love-care and the absence of hatred or hostility. Also, it preached truth (Satyameva Jayate). In myth, Dacoit Ratnakar was transformed into the saint Valmiki. Chand Ashok became Dharma Ashok. A parallel is Tyaga (sacrifice), like that of Purushottam Rama in the great Epic Ramayana. If the Mahabharata is considered, then it is justice for Krishna and Truth as Dharma for Yudhishthira. The consequences are known to all. The processes were often violent, but the ultimate goal was non-violent. This was notwithstanding the criminal history of mankind. India’s civilisation was most of the time silent, based on Parampara (tradition).

Tradition vs. Modernity

Despite repetitive invasion and administration by the conquerors, India remained mostly traditional in practices if one is careful in observing the major section of the population that resides in villages-hills-coastal belt. Of course, socio-cultural dynamics started changing fast post-British era. If this readily implies the impact of colonisation, then it will again be a conclusion in haste because the culture of the Heartland hardly changed with the advent of modernisation. One example may be the British demarcation of certain areas in newly formed towns as ‘Civil Lines’ when it developed physical infrastructure by roads and restaurants.

India’s tradition was not in a vacuum – it had an oral tradition that was very much knowledge-based. One example could have been Nalanda, which was destroyed by the foreign invaders. Some knowledge bases have remained, however, whether or not appreciated by the modernists or wise people, budded in the western formal education system.

Whose Indigenous Knowledge?

Knowledge was never monopolised in India despite the Brahminical tradition. Of course, knowledge of some was punished or destroyed, like that of Eklavya in the Mahabharata or the unwelcome assassination of Shambook in Ramayana. It seems difficult to pinpoint whose knowledge base – it could have been of Dronacharya, Bhishma, Rama, Vyasdev, Kautilya, Shushrut, Aryabhata in the remote past and Ramakrishna-Vidyasagar of the not-too-distant past. Evolution of indigenous knowledge and Indianization moved in parallel.

Economics and Politics

An idea has been injected over the past decade or so that one has to be parochially known as a Bengali, a Kannar, a Marathi, etc., for jobs or ethnicity or for an understanding of demographic composition; one offshoot is to find out a Bengali who entered India, particularly West Bengal, without a passport or visa. It is a different matter that there were no passport-visa till 1914 in the world of countries. A large section of the formally educated population has been tutored to cultivate hatred for a particular religious community, often based on the understanding that Bengalis are of that community. The Bengalis of districts like Murshidabad in West Bengal are mostly Muslims, and the Bengalis of the Sundarbans delta are both Hindus and Muslims. But how come the country is to be seen as one of only Hindus and Muslims as a binary division? There are Jains, Christians, Parsis, Buddhists and non-religious individuals. Is there anything wrong with humanity if one is only a human being?

Electoral-political necessity belongs to the core state. Social-cultural necessity distances itself from political necessity. The problem is that West Bengal society is basically a political society. The name of West Bengal is pronounced in political circles because it is probably much different from other states of India in its federal structure, by being a state with the same language and food habits as a neighbouring country post-1971. Partition-1947 was probably not a monopoly Bengali responsibility. The question of Bengali religious identity was not in circulation till 1971, since 1947, which did not provide any evidence that non-Hindu people were distributed by geography. If so, it needs more and better understanding of how and why Bengali pays the price of being Bengali because of the same or similar language as the people of a neighbouring country. West Bengal is not a sovereign country.

Undeniably, politicisation has grabbed most of India’s apolitical space, or intelligent people have started believing so, often helplessly, because of fear. The state has overpowered society, and society has no law to rule the state. The state has or it makes, including the making and erasing of history.

India and Indianisation

While India is a people residing in a specified geographic area protected by the sovereign state, Indianization reflects the character of the people through their ethics and practices. The practices show the dynamics of society that is more than the nature of the state. It is in a way India’s ideology that rests on inter-dependence, fraternity, trust, mutual respect and acknowledgement of diversity. All these requirements are non-negotiable and non-transferable. This means there is no scope and space for untouchability in society.

A society like India envelops is a unit in justice that is non-enforceable other than aberrations preached and executed by non-state actors like Khap Panchayat of Haryana or Ranvir Sena of Bihar or Salwa Judam of Chhattisgarh, and so on. The state is a unit in law. Justice is non-reachable in the absence of an enforceable law. This is where India stands, and not Indianisation. In the Epic Mahabharata, Draupadi got justice not in the court of Dhritarashtra, though he symbolised law; Justice was delivered through a war of justice. Law thus works or does not work on a canvas that remains narrow.

Indianisation, hence, is a cultural construct while India is a geographic-political-economic construct. Let there be no stretch of imagination that culture, on the one hand, and political economy, on the other, are wide apart. Both work in the same geography.

Tasks Ahead

Indianisation is not a matter to be enforced. India is a country with a geographic territory and hence law-enforced by the state. Indianisation lives in Gandhi-Buddha-Chaitanya-Rabindranath-Gokhale-Periyar- Subhas – to name a few, for their understanding and practices to be understood as lessons. The post-modern political economic dynamics may target to demolish that universal ethics embedded in humanity as described perhaps best by Rabindranath: ‘Eyi Bharater Mahanaver Sagartire…’ (On the seashore of India’s great humanity).

Let the people of India not be confined to a cardinal number called population. Population is more of a state need for derivative numbers for administration, while people are a social need. People project Indianization. The task remains to form a social garden for the people budding in humanity that is universal ethics.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By