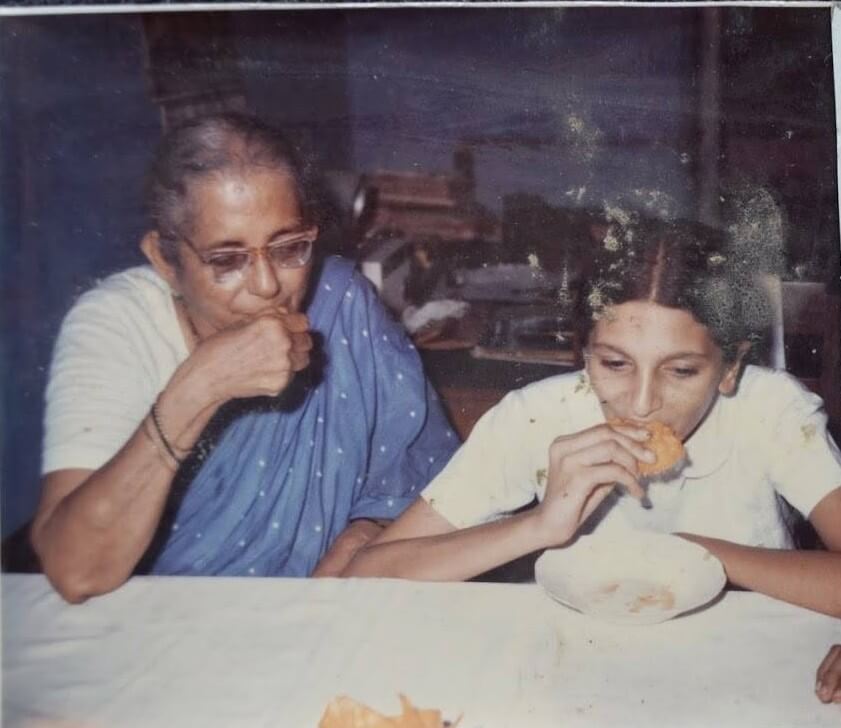

Her grandmothers’ kitchens were family hearts, filled with food, stories, and love. Their cooking and devotion created lasting, cherished memories, reminisces Kavita, exclusively for Different Truths.

My grandmother’s kitchens were the heart of their family homes. In each of their homes, the kitchen was the place where we all gathered to eat, exchange stories of our lives, and celebrate being a family. These were the kitchens I often return to in my memories. In my mind’s eye, I see the family, hear the conversations and the laughter, smell the wonderful aromas, and yearn for the hands that cooked the delicious food with love and devotion. The central figure who radiated warmth and love, and towards whom we all gravitated, was my two grandmothers. Two strong women of faith and belief in the sanctity of family created a welcoming space for all of us. Two women who embodied all the solid core values passed down to me through their gentle, calm, and caring personalities. Two wonderful women who put love into every dish. Two grandmothers who never considered cooking a chore, but an act of love and devotion.

The kitchens in their homes were not simply rooms but places where every object told a story—objects that held history within themselves, replete with family reminiscences that have created an unforgettable heritage. Like the city of Bombay, where my two grandmothers’ homes were based, I have always had a deep and lasting emotional attachment to the food prepared there and its connection to the importance of family.

Paternal Grandmother’s Kitchen

We called my paternal grandmother Aai, which in Marathi means mother. The kitchen in her home was spacious, where the light poured in through windows with old wooden slats. The house built by the British in 1894 was large by Bombay standards. All the rooms in the home were large and airy, and the kitchen with its stone floor was no exception. A spiral wrought-iron staircase at the back of the kitchen usually had a cat or two sunning itself lazily on the winding steps. The small common garden between the one-storeyed bungalows (we were in the first of the seven bungalows in the colony) and the lemon tree offered a tranquil view from the back door. It was a kind of haven in the middle of the city. I often stood there looking out at the trees shimmering brightly in the hot Bombay sun.

In one corner of the kitchen was a small stone mori, or a place to wash the utensils. A gas burner rested by the main wall, and beside it, gleaming brass pots for storing water were placed in a sort of pyramid formation, with large pots at the base and smaller ones on top. The pots were scrubbed using a mixture of tamarind paste (tamarind soaked overnight), rubbed vigorously into the pots with coconut fibres and washed clean. There was also a mud matka, or pot with a covered lid, for drinking water. A small wooden dining table with four chairs occupied the other side of the kitchen from the gas stove. Since there were many of us during celebrations and Jewish holidays, we carried our plates of food to other rooms to eat. The younger children usually sat at the table. In one corner of the floor, there was a small grinding stone and another gadget called a veli, a small flat wooden platform to sit on, with a sharp round metal object with metal spikes at the end of it for scraping fresh coconut to extract coconut milk as well as coconut flakes. In Bene Israel Indian Jewish food, coconut is widely used in many dishes. Since the Bene Israel Indian Jews had their origins in the Konkan coast, the availability of coconuts strongly influenced the use of this ingredient.

The Mango Season

Summer is the season of mangoes in Bombay. When raw mangoes became available, my grandmother bought them, chopped them into small pieces, and placed them in large ceramic barnis or jars, adding jaggery, turmeric, chilli powder, and various spices like cloves and cardamom to the mangoes and some raisins, soaking all of it in brine. She then covered the jars to let the marination take place. In tropical countries, the heat of the sun allows the mixture to do the cooking naturally. Grandma was making her famous sweet mango pickle, or muramba, as we called it in Marathi. When it was ready, she gave one jar to each of her daughters and daughters-in-law. We enjoyed the muramba with our meals, and the pickle vanished quickly. One recipe for mango chutney is in the Bene Israel Cookbook from 1986.

My maternal grandmother’s kitchen was smaller in size compared to my paternal grandmother’s kitchen. There was only one small window with bars. Here, too, we all gathered to eat, enjoy each other’s company, and help with the cooking in our roles as chief taste testers! We were a much larger family with five aunts and four uncles, their spouses, and many of my cousins. Again, it was my little grandmother, or Ma, as she was fondly called by all of us, who was the central figure. Her home was on the first floor of a very old building. In the main room, there was a long dining table where we gathered on Saturdays for the Sabbath prayers. So, we did not have to worry about space for eating meals. Like my other grandmother’s kitchen, there was a small mori with a few pots on a low ledge for storing water. The food was cooked on a kerosene stove. It was in this kitchen that I sat on a paat (low flat stool) between my Uncle Aaron and my cousin Isaac and ate a spicy potato vegetable dish till my eyes watered. They teased me mercilessly about my low tolerance for the heat!

Besan Laddus

Two dishes which were my favourites in my grandmothers’ kitchens were Birda (flat white beans) and Besan Laddus (protein balls made with chickpea flour).

Birda was a staple food at my paternal grandmother’s home. This is a typical Bene Israeli preparation. I remember the beans with their brown skin being soaked in water overnight and peeling them in the morning with one hand and with the other holding my nose, as the water had developed a strong smell. Still, I loved to do it! It was pure joy to watch the white beans pop out of their brown skin as they slipped and slid through the fingers. It is an unforgettable tactile experience. The recipe is included in the images from the Bene Israel Cookbook from 1986. The birda, which is made into green masala curry (recipe in images), was eaten with hot chapatis in my grandmother’s home. There is a historical significance associated with this dish as well, which is mentioned in the images. The reference to the month of Ab is that it is the first month in the Hebrew calendar and is often associated with several festivals and events, according to Jewish tradition.

My maternal grandmother’s special was besan laddus , round sweet balls made from gram (chickpea flour). It is impossible to forget the vision of my grandmother sitting on her haunches patiently sautéing the gram flour in ghee (clarified butter) till it turned golden brown. Then Ma pulled the hot mixture and shaped it into perfectly round balls by rolling each one in the palm of her hand. The neighbours all knew when Ma was making besan laddus as the lovely aroma wafted out of her kitchen into their homes. When I was nine years old, Ma made twenty-five besan laddus for my tuck box to take to boarding school. I’m not sure why she chose that number. My cousins still write to me and tell me how they remember hanging around for leftovers!

We make Besan Laddus in our home

Little Ma appears in every sweet bite

(lines from my poem “The Ballad of Little Ma”)

Spouse’s Besan Laddus

My spouse makes besan laddus at home whenever we have a strong craving for them. They are a constant temptation to eat as a snack and don’t last long. He adds toasted cashew pieces, icing sugar, and pumpkin seeds to the mixture after letting it cool first. Then he shapes it into round balls. We can’t imagine how Ma rolled the hot mixture into balls and never complained about feeling a burning sensation in the palms of her tiny hands.

Whether it was Birda or Besan Laddus, it was Jewish cooking at its most delicious and made the culinary experience personal and a precious lasting memory. My grandmother’s kitchens were the soul of their homes. For me, they will always remain culinary sanctuaries.

Photos by the author

By

By

By

By