Prof Bhaskar notes, exclusively in Different Truths, that pre-1914 free movement fuelled colonial growth. Today, Bengal-Bihar migrants face “ghuspaitiya” labels; he asserts that documented facts must override suspicion for these workers.

Free movement of people has been ongoing since time immemorial. Before 1914, there was no system of passport-visa for the cross-country movement of people, though there were many politically sovereign countries. Most of those who got relocated were from Western Europe to North America and South America, mostly under the influence of industrialisation in Western Europe. Some were, of course, drawn by the colonial masters, mostly Britain and France, to add to the wealth of nations. The precise point is the movement of people as labourers or as traders-philosophers-saints was in history, whether documented or not.

My purpose here is to briefly focus on intra-country relocation through the movement and migration of people. This, however, may not escape some phenomena linked with or as a consequence of inter-country relocation. There was a time when there was a two-way movement of people between West Bengal and Bihar – teachers, doctors, poets and novelists from West Bengal used to go to undivided Bihar, like in the areas of Madhupur-Giridih-Hazaribagh-Ranchi-Deoghar-Simultala, while people from Bihar mostly followed the Marwaris to work as labourers in Kolkata and a few to get an education at Calcutta University.

This went unquestioned and unabated during both periods, pre-1947 and post-1947. In the recent period, some of these people who migrated from Bihar started residing in West Bengal for better education, housing, and jobs, while many of the archaic houses in Bihar that the temporarily migrated Bengalis used to stay in got dilapidated or abandoned.

A new kind of nationalism based on suspicion of ‘ghuspaitiya’ (infiltrators), often state-sponsored, cropped up during the past decade or so that went after Bengali relocated people engaged as workers in states other than Bihar. Even some of the federal states on the circumference became alert and started taking actions based only on suspicion, alleging that these relocated workers were from the neighbouring country, Bangladesh, or even from Myanmar. A kind of fear and hatred was generated in the process. The semi-literate, semi-conscious people started talking in state vocabulary as if the demographic disaster was imminent because of infiltration from Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Relocation of Labour

Most of those who got and get relocated were from the more disadvantaged districts like Malda, Murshidabad and Cooch Bihar, where, because of the unwelcome 1947 Partition, most of the settled people were Muslims and linguistically Bengali. Many of them had developed work competence by inheritance, like that of a mason and goldsmith. India’s unorganised segment is characterised mostly by caste-community-based division of labour.

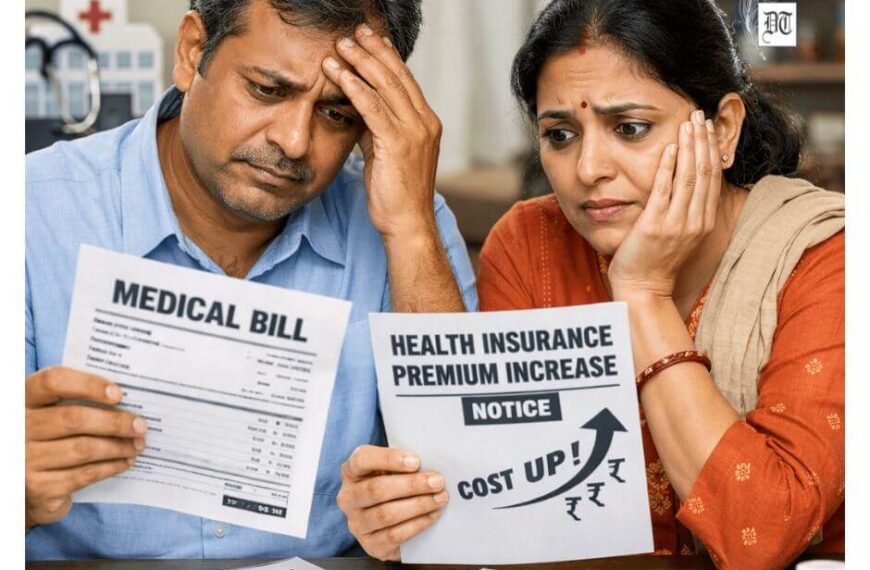

Had they moved intra-state, like to Kolkata and Howrah in search of jobs, it would not have created demographic discontent – the discontent came as they moved out of West Bengal. It is common sense in the economics of labour – labourers from Orissa move out to work in Gujarat, which creates a vacuum in Orissa that is filled by the Bengali labourers. And workers move out of Kerala, which is filled with Bengali labourers. This is the same as labourers moving out from Punjab, which is filled in by the labourers from Bihar.

Though cross-border movement of people is outside the purview of this note, it remains a question at what point it is inter-country and at what point intra-country movement of people, if one keeps in mind the 1947 partition, the 1971 war and the forced relocation of people, by then landless, assetless and some separated from relatives and neighbourless.

The revolution by terminology like ‘ghuspaitiya’ (infiltration), setting an arbitrary point of time in the history of India, may not be readily acceptable to people on either side of Bengal – West Bengal and Bangladesh. It has remained a much bigger question if Partition-led independence was acceptable to the people then living in East Pakistan, if the history of decolonisation of all the countries is considered – all got decolonised between 1945 and 1965, except for South Africa. It is not clear to the same language on both sides of Bengal what had been the hurry to save 20 years – this is for sure not an argument in favour of foreign rule in India.

The agony remains for Bengal was partitioned, not the United Province or Bihar or Madhya Pradesh or Gujarat. Rather than addressing that problem, the new Avtar have arrived as ghuspaitiya (infiltrators), which may be clinically examined by the competent institutions. What demographic number or arrangement changed in West Bengal and India over time, say, post-1971? Census 2027, which is delayed by six years, may also take into account this issue.

It may not be that the people who left Bangladesh post-1947 or post-1971 must live in West Bengal only. In search of jobs, some of them may get relocated to metropolitan cities like Delhi and Mumbai and get the scope to live in slums. The ruling authority generally suspects slum dwellers for several reasons, and when the dwellers speak Bengali, the suspicion probably gets multiplied by a number more than one.

It remains baffling when the entry of people from the bordering region becomes synonymous with ‘Bengali infiltrators’ when, in reality, there may be many tunnels and channels through which people move around, often without understanding state sovereignty. One example may be people in the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) or Arunachal Pradesh, where some gossiped that people also moved in from Mongolia. This is, of course, subject to scrutiny.

Discovering the Non-existent

The problems may be unnumbered, like ethnic composition, like vote banks, like security of settled people, trafficking, law and order and all that. The state needs to be concerned, but surely not based on suspicion or personal whims. The SIR (Special Intensive Review) launched first in the state of Bihar, pre-election, 2025, and then in West Bengal, among some other states in India, may have a hidden agenda to discover what does not exist, but by then, some people at the bottom who remain ‘consequences of state actions’ will have left the workspace. Suspicion multiplies by a number more than one. Unnumbered Adivasis in West Bengal declined to be tested by SIR, and Adivasis, by no stretch of imagination, can be ‘ghuspaitiyas’ (infiltrators).

There are people in India, like the Banjaras (gypsies), who move around and set up tents where they live and produce goods for sale. It may be ridiculous to find out if they are infiltrators – of course, they get relocated based on their own choice and season. The fact is, India’s civilisation is much bigger than the suspicion of the state authority – people live their lives rather than spending time on understanding the intricacies of state operations.

Relocation is a socio-economic aspect, and infiltration is a state concern. Each one may alter the internal dynamics in the routinised system. Relocation may also invite danger for the people relocated long distances, like the adverse impact of the abrupt declaration of lockdown in the recent past. Ghuspaitiya (the act of infiltration) also invites danger, as in the state of Assam, if media reports are taken seriously. Either way, people face the consequences. What is needed is to take out the ghuspaitiya (infiltration) issue outside the frontier of electoral politics.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

Prof. Bhaskar Majumder, an eminent economist, is the Professor of Economics at GB Pant Social Science Institute, Allahabad. He was the Professor and Head of the Centre for Development Studies, Central University of Bihar, Patna. He has published nine books, 69 research papers, 32 chapters,15 review articles and was invited to lectures at premier institutes and universities over 50 times. He has 85 papers published in various seminars and conferences.

He also worked in research projects for Planning Commission (India), World Bank, ICSSR (GoI), NTPC, etc. A meritorious student, Bhaskar was the Visiting Scholar in MSH, Paris under Indo-French Cultural Exchange Programme. He loves speed, football and radical ideology.

By

By