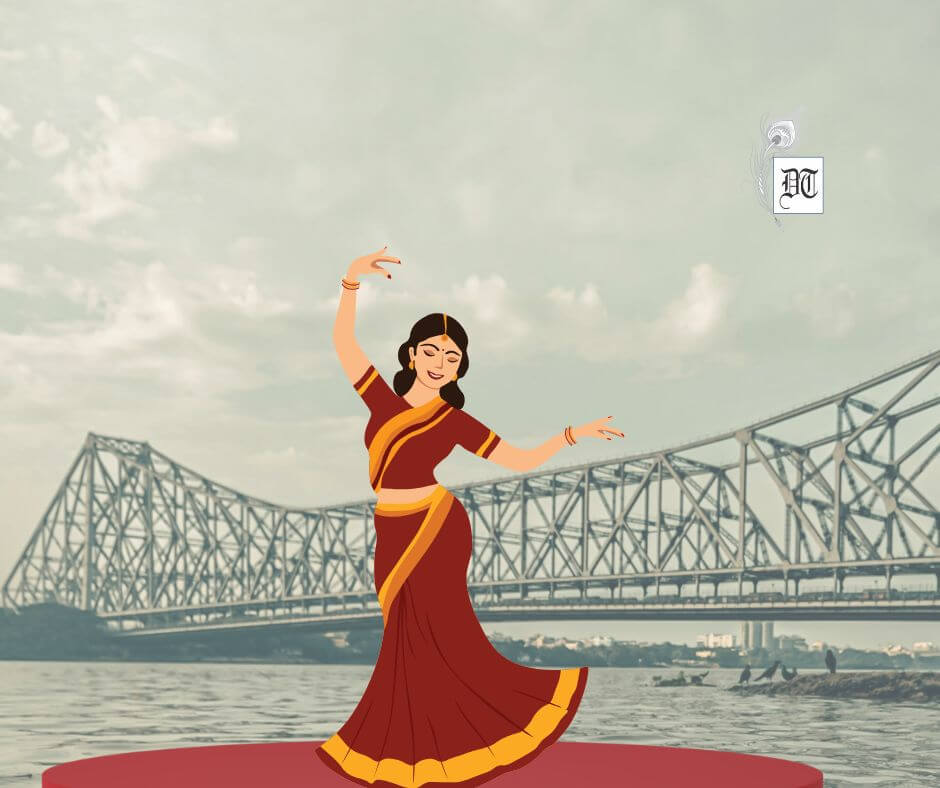

Bengal: Brilliant, rebellious, and brimming with genius. Why, then, does this intellectual powerhouse lack a classical dance form, asks Sohini, a renowned danseuse, for Different Truths.

I was born into a Bengal that worshipped poetry, fed on politics, and raised its children on philosophy and fish. I grew up surrounded by books, arguments, Tagore songs at dawn, and the intoxicating arrogance of a culture that believed it had already given the world everything worth giving.

And yet—every time I stepped into a classical dance class, whether Bharatanatyam, Odissi, or Kathak—one question followed me with the persistence of a Kolkata tram:

Why doesn’t Bengal, with all its brilliance, have a classical dance form?

Over the years, as a performer, scholar, and incurable Bengali romantic, I’ve come to understand the answer.

It is personal.

It is political.

It is painful for us.

Because Bengal raised thinkers, not disciplined bodies

My childhood was filled with people who believed intellectual suffering was a legitimate art form.

Everyone had opinions, philosophies, and manifestos—but ask the same people to sit in Aramandi for ten minutes and they would rather declare a hunger strike.

Odisha shaped Odissi through temple sculpture.

Assam shaped Sattriya through monastic discipline.

Bengal shaped adda—that glorious, chaotic, caffeine-fuelled tradition that kills all structure and births all genius.

In Bengal, the body was always secondary to the mind.

Which is beautiful.

And disastrous.

Because colonial morality wiped out the women who held the grammar

Classical dance survives through communities—devadasis, maharis, kirtaniyas, and gotipuas.

Bengal had them too: nachnis, baijis, temple dancers, and ritual performers.

I have danced in villages where the history still hums through cracked terracotta, but the lineages no longer exist.

The bhadralok erased the very women who could have given Bengal a classical form — and then pretended nothing was lost.

We killed the root, then wondered why the tree never grew.

Because Tagore gave us wings, not a spine

I adore Tagore.

Every Bengali does.

He gave us a universe of melody and movement.

But Rabindra Nritya was meant to liberate, not codify.

Its beauty lies in its fluidity — and fluidity cannot hold the burden of a classical canon.

Tagore taught Bengal to fly.

Classical dance requires an anchor.

Because our folk traditions were too honest for our refined egos

The Baul, the Raibeshe, the Kirtaniya, the Gajan dancer — Bengal’s body cultures are wild, devotional, muscular, and unashamed.

But the bhadralok palate, polished by colonial varnish, called them “rustic”.

We were too busy performing sophistication to honour the raw brilliance in our own backyard.

As a dancer, I often feel the ache of what could have been — the grammar we lost, the tradition we never allowed to mature, the lineage we refused to protect.

Because Bengal is addicted to rebellion

I say this with love: Bengalis cannot follow rules.

We rewrite, reinterpret, rebel, and reimagine.

Which is why Bengal excels in literature, cinema, theatre, and music — art forms where genius can explode without a codified structure.

Classical dance, however, demands surrender.

And Bengal has always chosen revolution over surrender.

So why does Bengal have no classical dance form?

Because Bengal is not a classical civilisation.

It is a restless, volatile, incandescent one.

Because Bengal values the mind over the body, the argument over the ritual, and the idea over the lineage.

Because Bengal never wanted to move in perfect symmetry — it wanted to feel, fluctuate, fracture, and reinvent.

And perhaps that is the truest thing about us Bengalis.

Our culture is not a sculpture carved in stone.

It is a flame — alive, unpredictable, and unwilling to be trapped in codification.

As a dancer from Bengal, I stand on a land that has no classical form — yet I carry within me a fire older than grammar.

Maybe that fire is our tradition.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

Sohini Roychowdhury is a renowned Bharatanatyam dancer, choreographer, artistic director, speaker, social activist, and professor of Natyashastra. She founded Sohinimoksha World Dance & Communications in Madrid/Berlin/Kolkata/New York. A visiting professor of dance at 17 universities worldwide, she won several awards, including the “Mahatma Gandhi Pravasi Samman” by The House of Lords, the Priyadarshini Award for Outstanding Achievement in Arts, and the Governor’s Commendation for Distinguished World Artiste. She has also authored several books, including ‘Dancing with the Gods’.

By

By

By

By