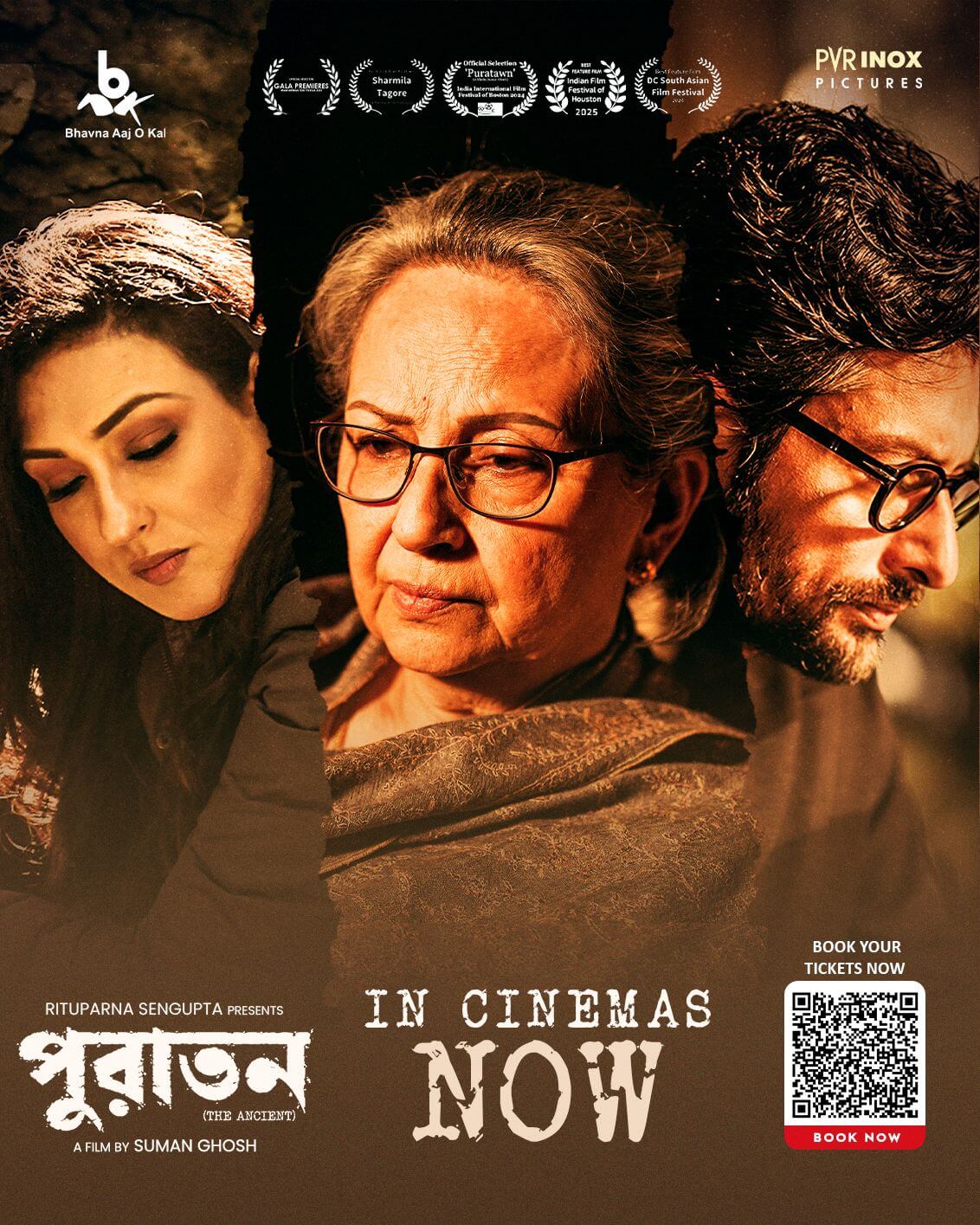

Sharmila Tagore delivers a poignant performance as an octogenarian in Puratawn, a drama about family, loss, and enduring connections, reviews Ruchira, exclusively for Different Truths.

One of the most glamorous heroines of the 1960s and 1970s, Sharmila Tagore has given a scintillating performance in Puratawn (ancient), which is being bandied as the actress’ swan song considering her advanced age and silent battle with cancer, even though she has doughtily refused to buckle under pressure.

In a remarkable coincidence, Sharmila Tagore, who herself turns eighty this year, vividly, flawlessly portrays an octogenarian woman who is slowly losing her grasp on both her memory and the reality that surrounds her.

The drama unfolds in a mansion in Konnagar, a little town located in West Bengal’s Hooghly district, where Ritika (played by Rituparna Sengupta) and her estranged partner Rajeev (Indraneil Sengupta) arrive to celebrate her mother Mrs Sen’s (Sharmila Tagore) 80th birthday. What ought to have been a cheerful family reunion is overshadowed by the realisation of her mother’s deteriorating mental health, possibly due to Alzheimer’s disease.

Sadly, the so-called family visit turns into a silent, highly underplayed confrontation with themes of loss, memory, and the inevitability of change.

The film opens with a single shot as the housemaid Heera (Brishti Ray) rushes around the house and discovers her ‘charge’ (the senile lady) anxiously waiting for her daughter to arrive. As the story progresses further, the viewers observe her mood swings (shall we call it?) and fluctuating emotions. She is depicted either calmly seated in her room or rummaging through mementoes and artefacts in the musty, dusty attic of the house—ornaments, bank passbooks, old letters, tattered photo albums, et al. Here we see a woman struggling to stay in touch with a lifetime of memories.

Paradoxically, in one scene, she accuses Heera of purloining her jewellery, only to discover it tucked away in a bookcase a few minutes later. When confronted by her daughter about this false accusation, she appears confused and bewildered. Pathetic case of a human mind oscillating between past and present!

Indeed, none of the characters can overcome their past, try as they might. Ritika is surrounded by a myriad of memories of her ‘vulnerable’ relationship, while Rajib seeks solace in old photographs of his deceased girlfriend Pritha. The story also probes the feelings of guilt that the characters harbour in their hearts. However, instead of sensational revelations, we get only subtle hints.

Rather than clinically explaining the decline of the protagonist’s health, the story focuses on her relationship with her daughter. Frequently, there are flashes of recollection when the elderly lady gets fleeting memories of her daughter as a toddler, her dead husband, and a favourite brother-in-law who had been a Naxalite.

We observe Ritika maintaining a painful distance as she watches her mother’s decline. She is perplexed as to how to assist her mother and what might bring her comfort. Again, the young couple is shown sharing muted chemistry, especially during the dinner-table scenes.

The moral of the story: The past and present of the lives of individuals cannot be separated. On the contrary, they are inextricably intertwined. Love, emotional bondage, and ties of blood are eternal rather than ephemeral.

On a personal note, being Bengali, the flick evoked the thought encased in one of Tagore’s famous lyrics, Puratawner hriday tootay aapni nuton uthbe phute (from the smithereens of the old, the new will sprout). Puratawn leaves the audience with a renewed sense of responsibility and hope for this generation, underlining the importance of staying connected to their roots.

Picture from IMDb

By

By

By

By