Pravat reviews Leaves of Silence by Prof RK Singh, which masterfully blends psychoanalytical depth, economical verse, and Japanese short forms to explore existential angst, for Different Truths.

Prof Ram Krishna Singh is an accomplished Indian English poet with expressive language entwined with symbolism. He is sensuous, and his poems are psychoanalytical. Prof Singh is recognised as one of the pioneers of writing verses with economy. In addition to mainstream poetry, he also explored Japanese short forms such as haiku, senryu, and tanka, using evocative imagery and poetic spirit. He enjoys the distinction of being one of the earliest Indian poets of the 1970s who attempted haiku poems in Indian English literature.

The current collection, “Leaves of Silence”, features 59 free verses, ten 4-line micro poems (i-x), and traditional Japanese forms of poetry: 3-line normative haiku/senryu and tanka. Broadly, the theme of the collection focuses on the psychic angst of old age, ailments, solitude, and introspective reflections, using striking images and symbols. Philosophically, he recounts the transcendence of the journey of life blended with happiness and nothingness: “challenging life and essence/ transient interludes of/happiness and nothingness” (Lasting Marks, p. 20).

Poetic insight is masterfully poised when he imagines, “I see a wind/waving the tree tops” (Four-Liners, vi, p. 76). The crafting of language and unison with nature is brilliantly poised in these two lines. Tonal style of the verses varies, from nostalgic (Talisman, p.18) to ironic and occasionally dense (Aching Defiance, p.71). Idioms and poetic phrases like “future isn’t set in stone”, “a brief smile”, “fertile solitude”, “sounds rippling through colours”, “shadows don’t change colour”, “hostage to the past”, and “noiseless peace” add a different dimension to his writings.

There is a poetic parallelism in the perspective of old age between WB Yeats and Prof Singh. WB Yeats was concerned about ageing and tried to embrace it over time. In the ceremony, on receiving the Nobel Prize in 1932, he said from the stage, “I was good-looking once like that young man, but my unpracticed verse was full of infirmity, my Muse old as it were. Now I am old and rheumatic and nothing to look at, but my Muse young” (Yeats, 2012: 46-61). Interestingly, Prof Singh engages himself in searching for solace through his own muse:

Dull notes of life

await reordering –

rhythm and pitch

behind closed walls, humming

to search my own music (Dull Notes, p. 37).

He spotlights psychology about old age and anxieties and laments, “in cold quietude bones creak in ageing cage await final decay” (Gelid Morning, p. 40). He bemoans the deterioration of health and ‘sleep divorce’ as a stasis of body energy:

no eremition no mantra works

to revive or reconnect

pre- or post-sleep divorce

negating nightmares distressed self

and dream disorders

that couldn’t be new memory

or poems with mad imagery

making sense in waking hours

I can’t bounce back from the brink

love humming beneath the surface (No Eremition, p. 43)

Referring to the reality of old age experience in life, WB Yeats portrays:

What shall I do with this absurdity –

O heart, O troubled heart – this caricature,

Decrepit age that has been tied to me

As to a dog’s tail?

(From the poem, “The Tower”)

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

(From the poem, “Sailing to Byzantium”)

Prof Singh has a sense of premonition and optimism about his own creation. The stanza below is an epitome of poetic vigour, conviction, and honesty embedded with linguistic maturity and transcendence of poetic brilliance:

when I proceed to the other world

you will feel my presence in history:

I’m enough for someone to love me

my happening impacts

despite the seasons regime or age (Intermission, p. 46)

His sensitivity is profound and aesthetic, and he wishes to rest under the wings of love and fragrance:

Bury me if you want to keep me alive

gently plant a night queen over my head

roses on both sides to keep love fragrant

and regain warmth from the cold little earth (After Death, p.49)

The poet is practical in his approach and at the same time spiritual in his perception. His inner consciousness dwells in the realm of cosmic beauty and he discovers universal oneness in the cyclical evolution:

Each one

an event in oneself

part of the whole:

we live in the world

the world lives in us

……

quest courage love

hope faith beauty

nature universe god

all fused within us (Know and Move, p. 14)

He philosophises life as “tempting moments and memories/ run into mirror of silence” (Talisman, p. 18) and a product of time: “sealed vial/ a product of time I am/ cut open & see/ how life spends me” (Four-Liners, x. p. 76). He contemplates that his life is forever in a cycle of salvation:

time degenerates

all dreams pious or vile

I am I forever

in chain for salvation (In Chain, p.15)

He explores socio-political perspectives and portrays the political drama with a satiric voice. The symbolic juxtaposition is interesting and innovative: “voting the same prophets” vis-à-vis “proclaiming the same faith” in the following poem.

General election:

voting the same prophets

attired differently

aspiring the same throne

proclaiming the same faith (General Election, p. 23)

He is concerned about the contemporary issues such as racism, trade wars, and religious conflict. Emotionally, he grieves:

memories may fade, but won’t die

like I die every day yet live (Heritage, p. 38)

Modern life turns out to be a hub of trade. He articulates it with a satirical tone in the poem “Trading” (p.22):

Once, animals were a threat

now we’ve become animals

He is reactive without fear or favour, and his poems, at times, appear expressive. He confesses:

I know my tongue to reveal the concealed

say the unsaid nativizing the form

that’s why I’m a poet (I’m a Poet, p. 45).

Emily Dickinson aptly said, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” and further she added, “Saying nothing sometimes says the most.” A few poems could have been coined artfully, replacing sexual overtones with symbolic expressions, of course, with a distinct exception to the poem “Body’s No Picnic” (p.60). Prof. Singh is honest and bold enough not to conceal the existential fact of life and ageing. The poem speaks a lot about relationships, mutual admiration, a sense of reconciliation and sublime fulfilment. I believe poet AK Ramanujan realised correctly when he said, “Love, you are green only to grow yellow.”

Japanese Short forms of poetry

Highlighting the Zen heritage of Japanese poetry, R K Singh writes: “The snippets of our complicated existence find images rooted in nature and physicality with whispers of the soul.”

R K Singh skilfully composes with brilliant visual imagery:

mazy passage

a hole in the stone –

secret exit (p. 78)

One of the profound haiku by Prof Singh steers the tragic situation in the urban landscape with seasonal sensibility:

the depth

swallowing life –

rain puddles (p. 84)

He is equally concerned about ecology and pens: “no birds sing/ in the sunless sky:/ mourning trees” (p. 84).

Sometimes, R K Singh’s tanka are characterised by freestyle five-line poems, more like kyōka and gogyohka. In the following two tanka, Prof. Singh eloquently juxtaposes the images across the pivot line (line-3) with a touch of cadence and poetic nuance.

The tanka “each time I’m born” portrays the concept of rebirth. It explores the stretch of life by poetically comparing analogous difficulties to the challenge of deciphering ancient Egyptian pictographic scripts and symbols (hieroglyphics). Indeed, it is a pragmatic juxtaposition of philosophical traits and ancient culture.

each time I’m born

I make new memories –

the load rises

so much inside calcified

with new hieroglyphics (p. 89)

He is influenced by the Buddhist philosophy and the concept of yin-yang and realises the impermanence of life, like the drift of a breeze.

wafts of breeze

brief walk in the lane

quietude:

first breath on earth with cries

ast breath in noiseless peace (p. 93)

The leaves silently breathe, grounding the tree in wisdom. In the open forum style of poetic expression, there exists a voice of silence between the words. Prof. Singh offers his expressive dynamics for the reader to dissect the perception of the poetic dimension of existential exactness. The poet might have reinvented the poetics to breathe in silence, as Rumi said: “This is how it always is when I finish a poem. A great silence overcomes me, and I wonder why I ever thought to use language.”

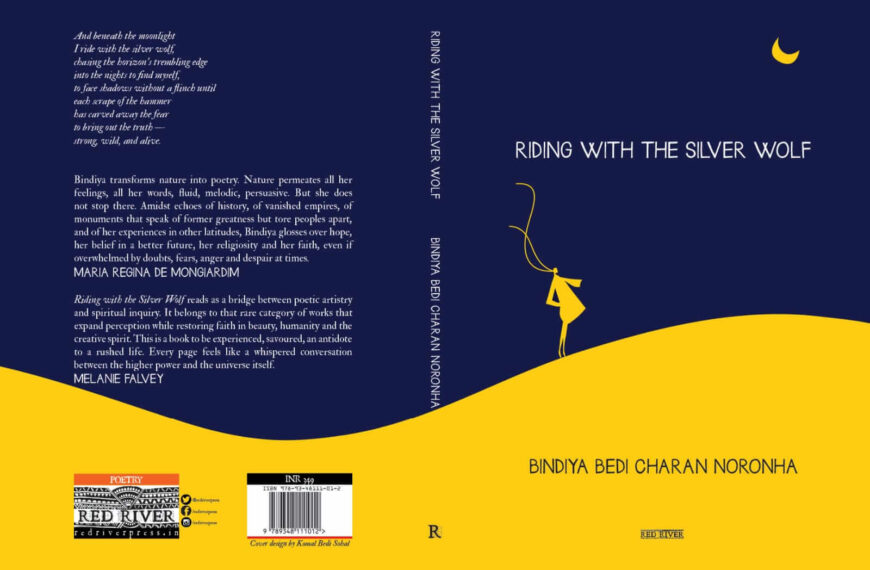

Cover photo sourced by the reviewer

Pravat Kumar Padhy, based in Bhubaneswar, India, obtained his Master of Science and a PhD from the Indian Institute of Technology, ISM Dhanbad. He is a mainstream poet and a writer of Japanese short-form poetry. His poem “How Beautiful” is included in the university-level undergraduate curriculum. He served as a panel judge of “The Haiku Foundation’s Touchstone Awards for Individual Poems” and presently is the Haibun Editor, Under the Bashō.

By

By

By

By

By

By

Thank you Dr Padhy for an in-depth and insightful review of my newest poetry book. I am also grateful to Arindam for featuring it on Different Truths.

R K Singh