Akash revisits Mumbai’s “Beer Man” murders, a two-part series exposing fear, media sensationalism, and flawed investigations, exclusively for Different Truths.

Crime, Fear, and the City

In the sprawling megacity of Mumbai, with over 15 million residents navigating through crowded train stations, footbridges, and poorly lit alleys, death often takes a subdued entry, lost among the many tragedies that besiege a metropolis of such size. But in the mid-2000s, something different emerged from the shadows: a string of gruesome murders targeting homeless men, mostly naked below the waist, and sometimes with beer cans suspiciously placed beside them. The media, gripped by sensationalism, dubbed the unseen predator the “Beer Man”.

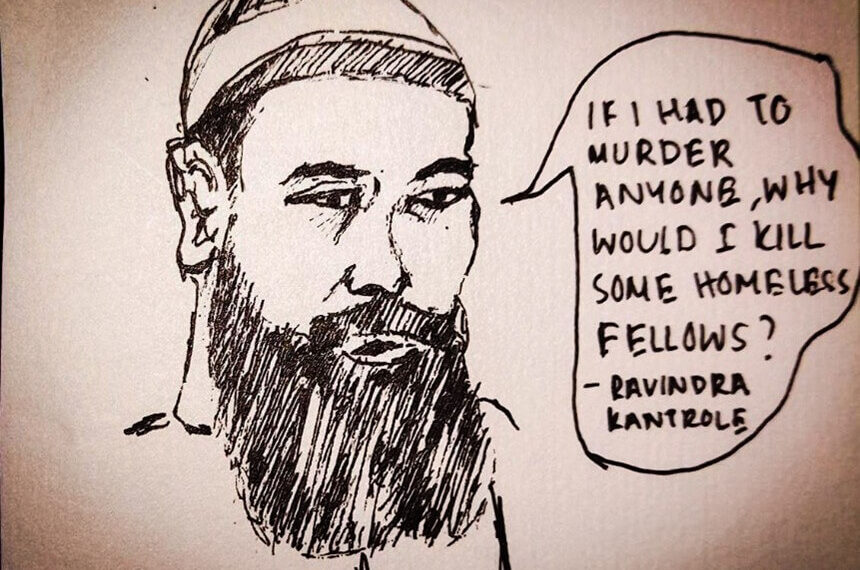

The moniker stuck. So did the fear. The streets between Churchgate and Marine Lines emptied earlier each night. Locals whispered theories about the killer’s motives and sexual inclinations. The police, caught between public outcry and investigative dead ends, zeroed in on a man named Ravindra Kantrole, who had since adopted the name Abdul Rahim after converting to Islam.

What unfolded next was a staggering tale of assumptions, weak evidence, biased profiling, and media hysteria. Despite his eventual acquittal, Kantrole remains imprisoned in the court of public opinion, a victim of both flawed policing and journalism that valued narrative over truth.

This article seeks to analyse the Beer Man case not just as a criminal investigation gone awry but as a profound reflection of institutional failure, media misrepresentation, and societal prejudices. It is a cautionary tale for criminologists, media professionals, and law enforcement about the dangers of oversimplifying narratives and criminal profiling based on visual or ideological archetypes.

The Emergence of the “Beer Man”

The first documented murder linked to the Beer Man occurred in October 2006. Vijay Gaud, a taxi driver, was found dead on a foot overbridge near Marine Lines station. The incident was barely reported, just another body in a city that recorded hundreds of unexplained deaths each year. The press buried the news in the inside pages, with less than 150 words. No one suspected this was just the beginning.

Over the following weeks, more bodies turned up—each victim a poor, homeless male, often found naked below the waist, sometimes with beer cans left nearby. With each murder, the city’s unease grew. People avoided Marine Lines and Churchgate at night. Whispers of a psychosexual serial killer took root. And then came the hook: the press coined the killer the “Beer Man”.

The name carried implications beyond its surface pun. It evoked images of a modern, alcohol-fuelled, sexually deviant murderer—someone operating outside conventional patterns of crime. The irony? Beer cans were found beside only two victims. But in journalism, repetition breeds truth. The press was more interested in selling stories than fact-checking details. Thus, a murderer was born not just in action but in imagination, shaped and defined by media narrative.

Press Sensationalism and the Power of Naming

The term “Beer Man” provided the media with a digestible archetype. In a society already conditioned by tales of Ted Bundy, Jack the Ripper, and Charles Sobhraj, the idea of a local serial killer operating with ritualistic intent was too irresistible. The beer cans became the ritual. The mutilated bodies became confirmation.

But this sensationalism came at a price. The media not only framed the narrative; it helped the police form their suspect profile. Instead of beginning with forensic or psychological profiling, authorities now had to reckon with a public that demanded a killer who drank beer, sexually assaulted his victims, and killed out of sadistic pleasure.

Newspapers ran wild with unconfirmed theories. Some publications implied that the killer was homosexual based on forensic findings of sexual assault. Others speculated he was wealthy; after all, he drank beer, a luxury not easily affordable by the city’s destitute. These deductions were not based on criminal profiling but on sensational guesswork that blurred the line between reporting and storytelling.

“If speculation had been a scrip in the Bombay Stock Exchange, millions could have been made,” quipped one critic of the press. That quote captured the heart of the issue: the story had become the product, and the public was the consumer. Accuracy was optional.

The Police Narrative and the Arrest of Ravindra Kantrole

Under intense public pressure and with growing fear on the streets, the Mumbai Police found themselves without leads. That is, until a sniffer dog traced the scent of a shirt left near a crime scene. The shirt led them to Ravindra Kantrole, now known as Abdul Rahim after his conversion to Islam.

The narrative fell perfectly into place: Rahim had a violent past, including gang affiliations; he looked menacing; and more importantly, he “looked like” a serial killer. He fit the mental image that the public and the media had constructed.

“On 22 January 2007, the sniffer dogs traced the shirt’s owner, and the police nabbed Abdul Rahim… The city breathed a sigh of relief.”

But was the relief justified?

When Rahim was arrested, he protested his innocence. “Sir, maine ganda kaam karna chodh diya hai. Mujhe yeh sab murder-wurder ke bare mein kuch nahi pata!” (I have left doing illegal stuff. I have no clue about the murders!).

Despite this, the police paraded their success. Evidence was shaky: a knife allegedly found on him (which proved nothing) and a confession during a narco-analysis that was legally inadmissible and full of contradictions.

Even more troubling was the forensic inconsistency. The so-called “confession” had Rahim admitting to killing fifteen people but denying any sexual motive, citing his religious beliefs. This directly contradicted the police’s initial profiling, which was built on sexual deviance.

But none of that mattered. Rahim had a beard. He had a criminal record. He drank alcohol despite being a Muslim convert. For the police and media alike, this was enough. He “fit the casting”.

(To be continued)

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Outstanding case…most interesting & thrilling ✨✨✨✨

Waiting for the next part, son…..

Exciting & stirring part💖💖💖💖💖💖💖