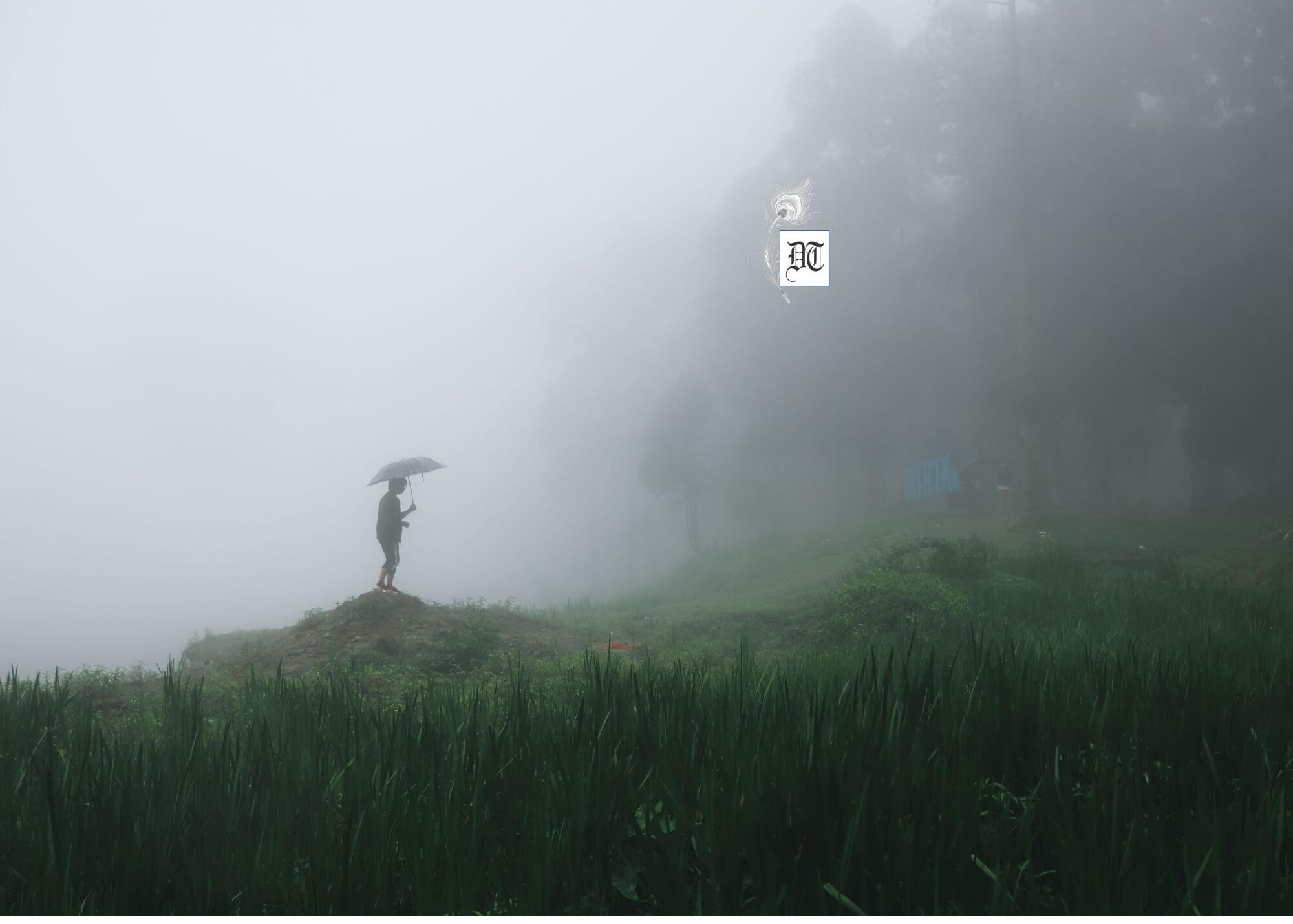

Ruchira elucidates that the monsoon stirred Rabindranath Tagore’s deepest emotions, inspiring lyrical, romantic, and mystical visions across his poetry, songs, and fiction, exclusively for Different Truths.

All Tagore aficionados and connoisseurs of Bengali literature are aware that the monsoon was by far the Bard’s favourite season. The reason for his fondness for this season is not hard to gauge. The vast expanse of land known as Bengal (both East and West) is a tropical region that experiences an infernally hot summer, where the seasonal rains from June to September bring much-needed relief.

His monsoon lyrics have been compiled into an anthology titled ‘Borsha Mangal’ (Auspicious Rain). The opening song reads “Namo (3) Karuna ghana namo hey” (Welcome, O Thou merciful Rain God). Another example is “Esho Shyamolo Sundaro,” which invokes the verdant rain to pour down joyfully, alleviating our incessant thirst and weariness. The blissful showers inspire myriad moods and emotions; for instance, the line “Mono more T ameghero shongi” (My mind flies off to the seamless skies in the company of the dense clouds) amply reflects this sentiment.

At times, Tagore compared the monsoon showers to the mighty Shiva of the Holy Trinity. In “Hridaye mondrilo damaru guru guru”, he likens the sounds of the heavy downpour to Shiva’s hand drum, with the dense dark clouds resembling his eyebrows puckered in a frown.

One cannot overlook the scene when the first spell of rain ushers in a bit of chaos in nature, as described in “Phirichhe kon oshim rodon kanon (2) mormori” (the winds rustling through the foliage and whistling around rain-soaked gardens sound like the wailings of a distraught, lonesome woman).

The incorrigible romantic that Tagore was, he found romance even in summer, the harshest season of all. In contrast, therefore, romancing in the pleasurable rains was merely a cakewalk. Romance takes on various forms—the lonely, disconsolate lover (or beloved) musing on past experiences and pining for an absent partner is one case in point. In “Ashaad sondhya ghoniye elo” (On a lonely Ashad evening, my mind is in a whirl as I sit in the corner of a lonely room), this state of mind is vividly captured.

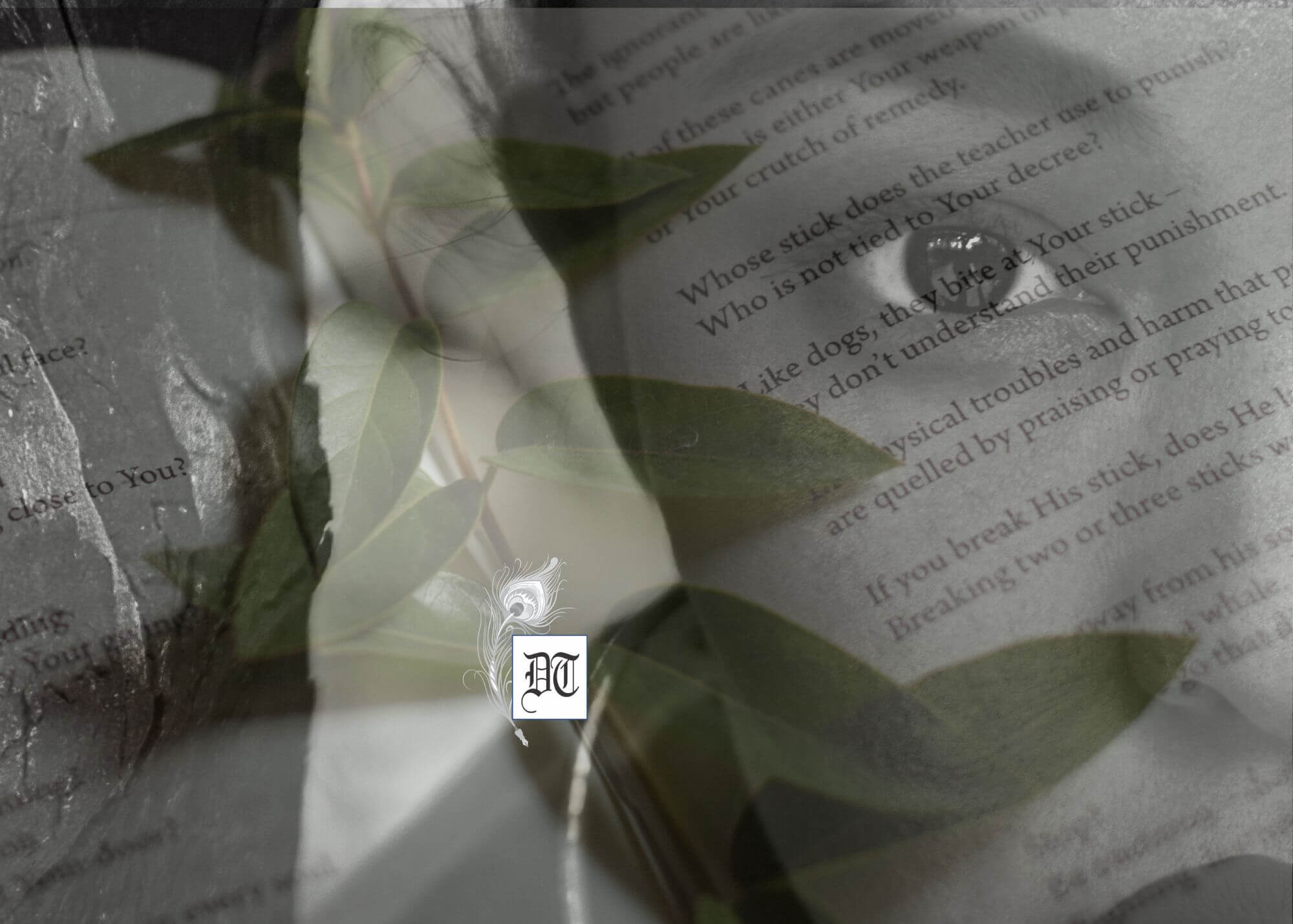

An intense, passionate moment is captured in “Shey korha shunibe na keho r nivrito nirjono chari dhar. dujone mukho mukhi goviro dukhe dukhi akashe jol jhore anibaar” (With dark, dense clouds muffling the sunlight, the love-smitten couple sit facing each other, sorrow and pain writ large on their countenances, while the incessant rains mute all external sound, and silence pervades everything).

Then we have the brave-hearted birohini (lovelorn damsel) who is ready to venture out into the stormy night for an abhisara (rendezvous) with her lover (an eerie reminder of the nocturnal adventures of Sri Krishna and Radha depicted in scriptures and folklore). This is evident in “Aaji jhorer raate tomar obhisar poran sakha bondhu tumi amaar…”

Incidentally, this song, used in Aparna Sen’s Bengali flick “Sonata,” sung by Shabana Azmi onscreen, gained considerable popularity.

In “swapne amaar monay holo…”, the lady regrets a missed opportunity; unfortunately, she was fast asleep when her beloved came knocking at her door in the dead of night.

To round off, we may recall a gem from the mediaeval poet Vidyapati, incorporated into ‘Bhanu Singher Podaboli’ by Tagore: “Bhara bhadar maha bhadar shunyo mandir more…” (In the month of Bhadra, when the monsoon reaches its peak, the shrine within my heart is gaping, empty, yearning for the beloved Lord).

True to his deep Baul spirit, Rabindranath Tagore saw visions of wandering minstrels, the Bauls, mirrored in nature at the height of the monsoon. Naturally, he penned “Badal Baul bajay (2) re Ektara” (The dense, rain-laden cloud assumes the contour of a Baul harping on his solo-stringed instrument).

The season likely catapulted the poet’s imagination into a highly creative mode, as he discovered music in the nature around him. In “Badal meghe. Madal baje”, the rumbling of the distant thunder appeared to him as if an invisible musician were playing the madal (mardala/country drum), with solemn notes reverberating through the skies.

Apart from poems and lyrics, Tagore, in his famous novella “Dui Bone”, compares the two sisters, Sharmila and Urmimala, to Varsha (the rainy season) and Basanta (spring) in that order. The former is placid, tranquil, serene, and graceful, endowed with a maternal quality of patience that alleviates pain and hunger. In contrast, the latter is vibrant, turbulent, bursting with gaiety, mirth, energy, and passion. This fictional work is a must-read for all those individuals who wish to gain insight into Tagore’s in-depth understanding of human (read feminine) psychology, as well as the intricate web of human relationships.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

A wonderful read for anyone interested in Tagore’s Literature. The write up delves deep into the thought process and helps create an understanding. It was a joy to read the same.

Thank you for a pleasurable read!