In the second part, Akash reveals that a man accused as “Beer Man” was acquitted, but public suspicion and police harassment outlived the court’s verdict, exclusively for Different Truths.

Dubious Evidence, Trial, and Acquittal

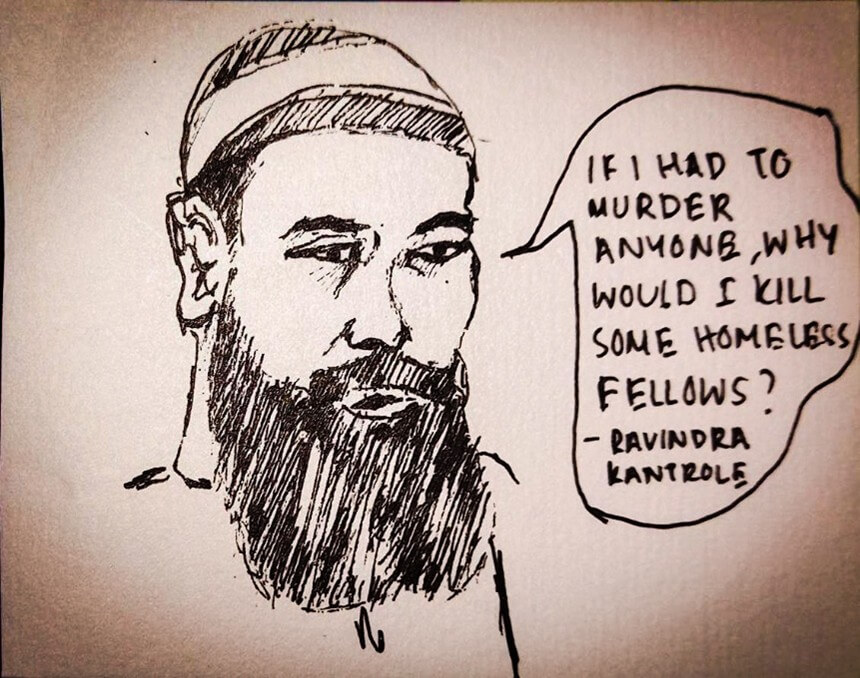

The arrest of Ravindra Kantrole, alias Abdul Rahim, was celebrated by the Mumbai Police as a breakthrough in what had become a spiralling public relations nightmare. The suspect, once a petty criminal, now stood accused of being a serial killer—the infamous “Beer Man.” But as the legal proceedings unfolded, the case against him began to crumble under the weight of its contradictions, missing links, and prosecutorial overreach.

The Evidence—or the Lack?

Central to the prosecution’s case was the shirt allegedly left at the scene of the crime, which a police sniffer dog linked to Kantrole. It was a thin thread to hang a conviction on, especially when dealing with serial murder. Aside from this, the police presented a knife that was supposedly recovered from his person. Forensic tests, however, could not conclusively link the knife to any of the victims. There were no fingerprints on the beer cans, no eyewitnesses, and critically, no DNA or trace evidence tying him to the scenes of the other murders.

A critical piece of the narrative was the use of narco-analysis: a controversial and now largely discredited forensic tool. Under the influence of sodium pentothal, Rahim allegedly confessed to several murders. But this confession was riddled with inconsistencies and contradictions. For instance, he described killing men in drunken rages but denied any sexual component, stating firmly, “Main Musalman hoon. Aise kaam nahi karta” (I am a Muslim. I don’t do such things).

This denied the foundational theory behind the murders—that they were sexually motivated.

Moreover, Indian courts have repeatedly ruled that narco-analysis cannot substitute for hard evidence. Its admissibility remains deeply questionable under Article 20(3) of the Indian Constitution, which protects against self-incrimination. Yet, it was the most cited “proof” in the media coverage of his guilt.

Judicial Proceedings: Justice or Performance?

When the trial began in the Sessions Court, the weight of public perception hung heavily over the courtroom. The police had already presented Kantrole as guilty to the media. Newspapers ran headlines like “Beer Man Behind Bars”, and television anchors hinted at a sexual deviant whose past caught up with him. But the case struggled in the courtroom, where law demands evidence, not headlines.

Kantrole was charged under IPC Section 302 (murder) and Section 397 (robbery or dacoity with attempt to cause death) for the death of a man named Shailesh Sutar. The prosecution, despite their sweeping claims about him being a serial killer, could only file charges in one of the many murder cases. The rest lacked evidence. No CCTV footage, no fingerprints, no reliable witnesses.

Sutar’s murder case, too, was built on circumstantial evidence. The prosecution claimed that Rahim had been seen loitering near the site. A few vague eyewitness testimonies followed, but none of them held up under cross-examination. No motive was proven. No physical evidence linked him to the murder.

In 2016, almost a decade after his arrest, the Sessions Court acquitted Rahim in the Sutar murder case, citing “lack of evidence and improper investigation.” The judge stated that “the prosecution failed to prove the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt.” Not only was the key murder unproved, but the other murders despite media assumption had never even been formally linked to him in court.

The Irony of Acquittal

The acquittal should have been the end of the story. A man falsely accused, eventually cleared by due process. But this wasn’t the case.

Even after being cleared of all charges, Kantrole remained under suspicion, not legally, but in public consciousness. For many in Mumbai, the name “Beer Man” had already fused with his face. As far as the public and some tabloids were concerned, acquittal merely meant the courts had failed, not that the man was innocent.

The failure to formally link the fifteen unsolved murders to Kantrole was not interpreted as his vindication but as proof of police inefficiency. Headlines subtly continued associating him with the crimes using phrases like “Beer Man Acquitted in One Murder” or “Suspected Serial Killer Walks Free.” These linguistic tricks poisoned public understanding.

For Kantrole, the battle may have ended in the court of law, but the war continued in the court of public opinion.

Life After Acquittal – A Marked Man

Acquittal, in theory, restores a person’s dignity, innocence, and social standing. In the case of Ravindra Kantrole, better known to the masses by the media-invented moniker “Beer Man,” the Bombay High Court’s exoneration did little to unshackle him from the chains of stigma. Though the legal system absolved him, public perception and police prejudice condemned him to a shadow life where his freedom came laced with fear, suspicion, and systemic harassment.

After his acquittal, Kantrole attempted to quietly reintegrate into society. But Mumbai had a long memory. Despite the court’s conclusion that there was insufficient evidence to convict him, many locals believed he had simply “gotten away with it.” In the labyrinthine alleys and underpasses of Mumbai where the murders had occurred, whispers followed him wherever he went. The media may have moved on to newer headlines, but the average Mumbaikar remembered the fear and the face associated with it.

He recounted instances of being stared at, whispered about, and deliberately avoided. Shopkeepers refused to serve him. Landlords denied him accommodation. Jobs were nearly impossible to secure. For all practical purposes, he had become a social leper.

“The tag of Beer Man had been permanently inked on his forehead, so much so that wherever he went, people talked in hushed whispers, before moving away from him.”

Kantrole’s life, post-acquittal, resembled a sentence of social exile. With no stable income, no family support, and no institutional rehabilitation, he lived on the margins, haunted by a crime he was never proven to have committed.

Worse than the public’s suspicion was the police department’s unwavering fixation. In interviews, Kantrole described repeated encounters with law enforcement who, despite the High Court verdict, continued to treat him as the prime suspect.

Whenever a similar crime occurred: a body found on the street, a homeless person killed under suspicious circumstances, the first person to be picked up, interrogated, or shadowed was Kantrole. He recalled being taken in for questioning multiple times without warrants or cause, simply because his name continued to float in internal memos and officer chatter.

This continued harassment reflected a systemic flaw: law enforcement’s refusal to admit investigative error. To acknowledge Kantrole’s innocence would have been to admit failure not only in catching the real killer but in destroying an innocent man’s life in the process.

Kantrole’s own words reflect the futility he feels:

“Mujhe hamesha meri daadhi, baal aur mazhab ke wajah se pakda gaya hai [I have always been targeted for my long hair, beard and religion].”

Indeed, his visible Islamic identity became an easy scapegoat for a police force under pressure to deliver a culprit, regardless of proof. The combination of his criminal past, appearance, and religious affiliation made him a convenient villain for a panicked public and an overstretched investigative unit.

He attempted to return to work as a police informant, hoping that the very system that had destroyed him would now help redeem him. But those bridges were long burned. He was no longer seen as a source of intelligence but a liability, a living reminder of a bungled case that the Mumbai Police preferred to bury rather than resolve.

Kantrole often spoke about trying to live a clean life. But what options does a man have when every door remains closed and every path leads back to suspicion?

While Kantrole battled for survival, another figure remained conspicuously absent from the narrative: the real “Beer Man.” Despite a brief period of calm following Kantrole’s arrest, no long-term resolution came. The killings stopped, yes but was it because the killer had been caught, or simply that they moved, changed methods, or stopped voluntarily?

The silence on the case in the years that followed signaled a disturbing possibility: the real murderer was still out there anonymous, unremarked, and potentially emboldened by the miscarriage of justice surrounding Kantrole.

What made this even more tragic was that no fresh investigations were launched after Kantrole’s acquittal. The police had already tied up the file with a neat ribbon; reopening it would mean admitting they had closed the case on the wrong man. As a result, the families of the murdered men homeless, nameless in many cases received no closure, no justice.

When Kantrole was arrested, he made headlines. When he was acquitted, his story barely warranted a footnote.

This silence wasn’t accidental. It was editorial amnesia, a refusal to correct the public record or challenge the original narrative that had gripped the city. Corrections don’t sell newspapers. Scandal does.

This absence of coverage post-acquittal created a one-sided historical record. For most readers who remembered the headlines from 2007, “Beer Man” was arrested, and that was the end. Few were told he had been freed. Fewer still cared.

This is one of the most chilling aspects of the case: not the wrongful arrest, but the institutional willingness to forget the truth because it did not serve the myth that had already been sold.

Institutional Failure, Media Ethics, and the Legacy of the “Beer Man” Case

The story of the so-called “Beer Man” is not just about a series of brutal murders in Mumbai between 2006 and 2007. It is also a sociological autopsy of how institutions—media, police, and judiciary can fail the very people they are meant to protect and serve. The case offers an alarming glimpse into how narrative can override fact, how prejudice can replace proof, and how the search for truth can be buried under sensationalism.

Traditionally, the press is called the Fourth Estate, a vital component of any democracy meant to question authority, expose injustice, and inform the public. But in the Beer Man case, the media morphed into a circus ringmaster, fuelling panic and peddling half-truths to boost circulation.

“If speculation had been a scrip in the Bombay Stock Exchange—millions could have been made by the newspaper companies.”

What started as a factual report of a body on a footbridge quickly spiralled into a thriller-like serial killer saga, embellished with unverified details and pseudo-psychological profiling. Only two of the victims had beer cans near them yet every article fixated on the idea of a killer who drank with his victims, turned on them, and left behind the evidence like a signature.

This irresponsible leap in logic is emblematic of a larger failure of journalistic ethics. Sensationalism replaced scrutiny. Entertainment trumped accuracy.

No major media outlet issued a proper correction or apology after Kantrole’s acquittal. No investigative effort was made to uncover how the narrative had spun so far from the truth. Instead, silence filled the void—complicit, telling, and dangerous.

While media failures are glaring, the institutional breakdown within the Mumbai Police is even more troubling. Under pressure to show progress in a high-profile series of killings, investigators clung to theories not based on evidence but on speculation and narrative convenience.

“The police started to fit their stories to match the narrative. This was a conspiracy akin to the JFK assassination and the single-bullet theory.”

Ravindra Kantrole, a reformed gangster with a religiously conspicuous appearance, was fitted into the role not through careful investigation but through a mix of circumstantial evidence, coercive tactics, and profiling biases.

Let’s consider the key failures:

· Sniffer dog evidence was treated as gospel.

· A handwriting sample was considered “proof,” despite indications that the note could have been planted or extracted under duress.

· A narco test, legally inadmissible, was flaunted as conclusive.

· The claim that beer consumption made the killer “not poor” is absurd at best and classist at worst.

· These aren’t just investigative missteps, they are symptoms of a systemic rot, where results matter more than justice, and public perception is more important than the truth.

· And most damning of all: no fresh investigation followed the acquittal. Once Kantrole was released, the case was dropped into cold storage. Justice was not just delayed; it was wilfully abandoned.

To the credit of the Bombay High Court, justice was eventually served, at least in a procedural sense. The court meticulously dismantled the prosecution’s case, pointing out the inconsistencies, the absence of reliable evidence, and the media-driven myths that surrounded it.

However, legal vindication does not equal social rehabilitation.

In the absence of police protection, media accountability, or public support, Kantrole’s acquittal felt hollow. He was free but not truly liberated. The very system that freed him offered no avenues for compensation, healing, or reintegration.

This reveals a missing link in the Indian criminal justice system: while wrongful convictions are acknowledged, there is no comprehensive framework for restitution, mental health support, or rehabilitation. The state washes its hands, leaving the falsely accused to navigate the wreckage of their lives on their own.

In the rush to capture, convict, and celebrate the arrest of the “Beer Man,” a painful reality was overshadowed the victims.

Most of the men killed were homeless migrants, nameless and faceless to the city they lived in. Their deaths were made into headlines, but their lives remained undocumented. Even today, there is little public memory or official record that commemorates them.

There are no memorials. No public inquiries. No justice.

This shows a class bias in both media and institutional response. Had the victims been upper-class, or women, or children, the response might have been more humane and long-lasting. But these were men from society’s fringes—drifters, addicts, poor labourers. Disposable.

The Beer Man case may have receded from the headlines, but it continues to linger in the cultural and institutional memory of Mumbai. It raises questions that remain disturbingly unresolved:

Why did no proper investigation follow the acquittal?

Why was no one held accountable for the police and media failures?

What happened to the real killer?

Why is there no policy in place for rehabilitating the wrongfully accused?

Why did the lives of homeless men merit so little care, even in death?

These questions are not just about a specific case. They are symptomatic of a broader structural apathy in India’s criminal justice and media systems, an apathy toward truth, accountability, and the value of human life at the margins.

Final Reflections and Conclusions – Beerly, a Killer or a Victim

The tale of the so-called “Beer Man” of Mumbai is not simply a crime story. It is a mirror reflecting urban India’s most uncomfortable truths: its treatment of the marginalised, its obsession with spectacle, and its institutional reluctance to admit fault. More than a chronicle of murder, it is the story of a man who became a metaphor: a metaphor for media irresponsibility, police shortcuts, and systemic cruelty.

Was There Ever a “Beer Man”?

This is the first and most haunting question. Based on forensic inconsistencies, contradictory evidence, and failed profiling, one cannot help but ask: was there ever a single serial killer at all?

The murders spanned over a year, with victims killed in different manners some stabbed, others bludgeoned. The only thread binding them together was their status as homeless men, a demographic that receives little attention and even less justice.

The so-called “signature” of the beer cans was only found at two scenes. Yet that minor detail snowballed into a narrative, pushing law enforcement into the dangerous realm of assumption-based profiling.

“This was just an indication of how the press was reporting, and twisting, the story to sell it, portraying a serial killer who left beer cans in his wake, to the readers.”

The actual killer or killers remained at large. No composite sketch was released. No DNA was matched. No deep forensic investigation was conducted beyond surface-level indicators. Once the media got its scapegoat, and the police got their suspect, the case effectively ended even as the truth remained buried.

In every criminal justice failure, there is a face that carries the weight of the system’s errors. In this case, it was Ravindra Kantrole: formerly a gangster, later a police informant, and finally a poster child for presumed guilt.

What’s tragic is not just his wrongful arrest, but the way his past and appearance were used against him:

His conversion to Islam was made into a suspicion.

His beard and long hair were made to resemble that of a ‘criminal archetype.’

His former association with gangs nullified the possibility of redemption in the eyes of law enforcement.

Even after the Bombay High Court acquitted him, the stigma remained permanent:

“Even though the court had acquitted me. For [the police], I am the serial killer who got away.”

Rahim was harassed every time a violent crime happened in Mumbai. He was followed, questioned, watched. He was forced into a life of permanent suspicion: a social prisoner, acquitted but never truly free.

This continued scrutiny turned his acquittal into a legal technicality, not a liberation. He was branded. His very existence served as a reminder of how narrative overpowers truth in the Indian criminal justice discourse.

Mumbai is no stranger to violence. But the “Beer Man” case reveals a new kind of urban danger not just from criminals, but from the institutions designed to protect us:

The police, pressured by media and public demand, forsook procedure for prosecution.

The media, seduced by headline value, turned half-truths into full-blown character assassinations.

The judiciary, though ultimately corrective, lacked the mechanism to compensate or rehabilitate.

The public, hungry for closure, accepted spectacle over scrutiny.

This confluence of forces created not justice but a theatrical illusion of justice. The city needed a killer. It needed closure. And so, it created one, not from forensic rigor but from prejudice, desperation, and fear.

The “Beer Man” saga must also be viewed within a larger societal framework. Several undercurrents shaped the case and its outcome:

1. Classism: The victims were homeless migrants, people often rendered invisible. Their plight was deemed unworthy of serious investigation until it became sensational.

2. Religious Prejudice: Kantrole’s conversion to Islam became an implicit red flag, making him fit the imagined profile of an anti-social figure.

3. Media Capitalism: The commercialisation of crime reporting turned an investigation into a serial drama, flattening nuance in the pursuit of virality.

4. Policing Failures: Over-reliance on pseudoscientific methods like narco-analysis and the misuse of handwriting “evidence” betrayed a lack of procedural integrity.

5. Judicial Inertia: Acquittal did not bring systemic correction. No one was held accountable. No one was punished: not the police, not the media, not the real killer.

Conclusions

Ravindra Kantrole, or Abdul Rahim, may or may not have committed unrelated crimes in his past. That is immaterial to the core issue here. When it came to the “Beer Man” murders, he was not proven guilty and thus remains legally innocent. But the institutions around him operated with a different assumption: that guilt could be constructed from a combination of his records, community prejudice, and public panic.

In that sense, the real tragedy of this case is that while the actual serial killer may have gotten away, an innocent man became the sacrificial lamb of a broken system.

“The tag of Beer Man had been permanently inked on his forehead, so much so that wherever he went, people talked in hushed whispers, before moving away from him.”

This is the story of a city that needed a monster and created one. It is also the story of a justice system that found convenience in conviction, and cowardice in correction.

And ultimately, it is the story of an unsolved crime, not just of murder, but of injustice, of negligence, and silence.

References

1. Ganjan Khergamker, ‘The Stranger Murders’, Fountain Ink, 4th December 2012

2. ‘India World Leader in Greasing Palms’, Times of India. 5th October 2006

3. ‘Police Map Beer Man’s Next Strike’, Mumbai Mirror, 14th January 2007

4. Marc Lallanilla, ‘What is the Single-Bullet Theory?’, Live Science, 20th November 2013

5. Lhendup G. Bhutia, ‘The Serial Killer Who Wasn’t’, Open, 28th July 2012

(Concluded)

Illustration by the author

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Outstanding… marvelous ✨✨✨✨

Heartbreaking 😔

Excellent 💖💖