Prof. Malashri reviews Alok Bhalla’s translation of ‘Kumarajiva: A Buddhist Monk on the Silk Road’ for Different Truths, detailing the scholar-monk’s journey translating profound wisdom despite crippling adversity.

“Buddham saranam gacchami“, a chant that resonates through the ages, in association with Dhamma (religion) and Sangha (community), the three principal tenets of Buddhism. Yet there are exceptional teachers whose destiny took another path.

Immortal words

will be carried across

the limits of Time

into Infinity (130).

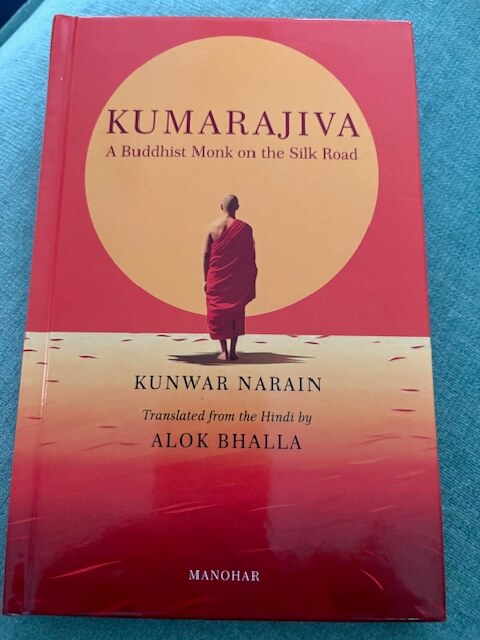

The profound wisdom of Kumarajiva is not widely known, despite the recent expansion of attention to Buddhist studies. The present book is Alok Bhalla’s translation of Kunwar Narain’s long poem in Hindi about the spiritual seeker, scholar and translator, Kumarajiva, who lived around 400 CE and sustained his intellectual pursuits despite several adversities. Though not as famous as Nagarjuna, Shantideva or Asvaghosha, the story of Kumarajiva is subsumed with life wisdom, even as it addresses deep spiritual questions. A ‘late work’ by Kunwar Narain, the poem humanises the Buddhist scholar by describing his imprisonment and ill treatment in parallel with his interior monologues on adhering to his faith and dignity. What strikes me as most significant is that Kumarajiva is compelled to break the tenets of Buddhist monkhood and become a householder, forced to drink wine and kept in prison for seventeen long years. Yet, he remains true to his quest for knowledge and enlightenment.

The poem is structured in three segments, the first being Kumarajiva’s childhood and apprentice years in Kucha, the second describes his long and humiliating incarceration in Lanzhou, and the third presents his recognition and liberation in Chang’an. Alok Bhalla’s poetic rendering, while faithful to the original, is exquisite poetry in itself. Philosophical concepts, internal dialogues, and external contraventions are interwoven in fluid phrases and verse, structured into a rhythm that leads one towards the mystique of spiritualism. The transference from Hindi to English never interferes with the flow of the mellifluous narrative. Bhalla successfully places Kumarajiva in his time, and also ours, as the sagacity of his life understanding offers rich lessons on personal ethics and social action.

Coming to a few details of the text, Kumarajiva was born in 344 CE in Kucha, and his parents ensured that he received the best of education, first in Hinayana Buddhism and then in Mahayana Buddhism. These places were along the Silk Road, which, as Bhalla informs us, is not a single pathway, but an amorphous region with a variety of terrains. As Kumarajiva was exposed to diverse influences and the intricacies of Buddhist knowledge systems, he began to question the meaning of existence.

This visible

incandescent world.

is the truth… is an illusion…

either all that is – from Being to Being

or emptiness – from Nothing to Nothing (55).

His chosen path was not that of a Buddhist preacher, but a student-scholar-translator and a teacher of Buddhist scriptures (52). In 384 CE, when Kumarajiva was forty years old, Emperor Fu Jian invited him to join his court in Chang’an. He sent an army under General Lu Guang to escort him to Chang’an; instead, Lu Guang conquered Kucha and established himself as its sovereign. He captured Kumarajiva and kept him as his prisoner in Lanzhou (16). Some of the deepest teachings in “mindfulness” emerge in the section called “From Kucha to Lanzhou” when Kumarajiva, in his prison cell, visualises the walls “built/ not of brick and mortar/ but of books” (92). Thereby, “seventeen years passed/ like a single day” (93). And a conviction emerged “that the present/ was like the past/ and will be like the future” (93).

Meanwhile, in Chang’an, a similar pattern of violence, usurpation, and return to power of the earlier dynasty happens. This time, Kumarajiva is welcomed by the ruler as the National Preceptor (guoshi) of the kingdom (17). He died in 413 CE, having translated thirty-five Sutras and two hundred and ninety-four scrolls. According to Bhalla, these translations are still consulted for their accuracy and the fluent harmony of the verses.

The ageing Kumarajiva, who had amply comprehended the meaning of the Buddhist doctrine of dukkha (sorrow, suffering), was in a contemplative and resigned mode. And some of the most touching thoughts on the fragility of life, and the meaninglessness of death, are to be found in this last section of the book,

“Consciousness of the phenomenal world/is not in conflict with knowledge of the transcendental. /The two are different; they do not negate each other” (123)

Elsewhere:

“Knowledge of the Self is neither religious nor profane” (123).

The last few verses that describe the liberation of Kumarajiva from his bodily existence are superb poetry, filled with tender piety, deep spiritualism and an unblinking acceptance of human vulnerability.

There are several reasons for reading this book. It’s about Buddhist monkhood without its usual image of the monk as a celibate, wandering preacher associated with a Sangha. Kumarajiva was disallowed this path and instead was destined to become a scholar-translator to whom we owe the preservation of several ancient Sanskrit texts through their translation into Chinese. His writings brought illumination to seekers in East Asia over generations.

Even more significantly, the book is valuable as poetry where words flow like a gracious stream, sometimes encountering boulders and sometimes swirling past with renewed energy. In the current trend of self-reflective books, long narrative poems are seldom composed. Kunwar Narain chose an unusual subject in Kumarajiva. The credit goes to Alok Bhalla for creating a gentle and melodious English rendering that will reach out to global audiences.

Book cover sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By

Comprehensive, informative and thought provoking.