Prof Bhaskar’s analysis delves into the unique cultural, social, and economic existence of post-independence Hindu Bengalis in India, exclusively for Different Truths.

Of the unnumbered wonders in the world, Bengalis as a tribe are one for unnumbered reasons. Since it is difficult to consider Bengali as a single unit of analysis for it is not a single clan, I shall try to locate it in time and space, of course keeping in mind the indefinite point of time when Bengali came to be visible as a distinct category and in parallel, both open and concealed geographic space where it is visible. What follows is mentioned below, that is, of course, never-ending and subject to further questions. I keep in mind undivided Bengal but focus mostly on post-independence ‘Hindu Bengali’ settled in India.

Bengalis cannot be separated from the geographic area where they get settled for social and economic existence. Hence, I shall encompass the geography also to understand the existence value of the Bengali.

One may discover Bengali as citizenship-less or stateless. One may discover Bengali as powerful citizens. One may discover Bengali in West Bengal, which is considered its geographic area, and one may find Bengali in most of the other states and Union Territories of India like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Delhi and Andaman Island, and a large number settled abroad. One may find a leisure-loving home-settled Bengali, and one may find an unsettled risk-loving, ambitious Bengalis.

Income-Poor and Non-Poor Bengali

For the settled Bengali in West Bengal, the differences in the income-poor and income non-poor Bengalis do not mean much, for both meet on the axis of equality at local bazar and cultural clubs, and both recollect the past in terms of Bengali songs and films, paintings and so on. Income-poor Bengalis also take pride in describing how much area of land they had in East Pakistan that, when added up, would have been more than the geographic area of undivided India. But that is a sense of pride in what they had or did not have. Bengalis are sentimentally sensitive (‘abegpravan’) by birth.

Food-centered Bengali

Almost all Bengalis are non-vegetarians; fish is auspicious for Bengali festivals. The question of purity-impurity in taking food is redundant for them. Bengalis are fond of food (mach-bhat). They eat and they feed. What they feed is not much different from what they eat – inviting and feeding is in their culture. They discuss food from the stage of purchase from the local bazar to the transformation of raw food into cooked food and ultimately to the taste received; this discussion occasionally includes describing the capacity of individuals who can eat much more than the community-average at a time point.

Culture-centered Bengali

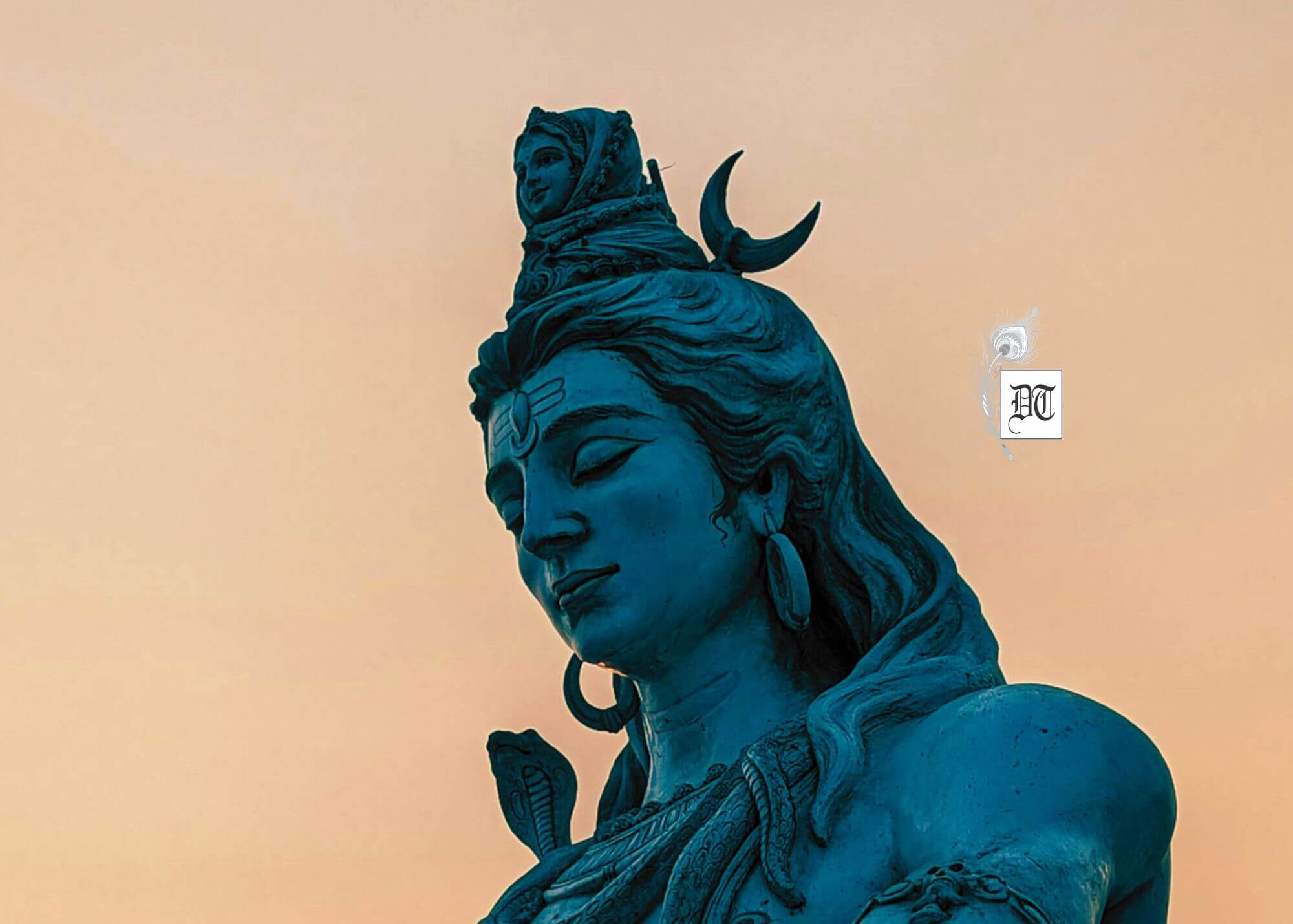

Culture has two centres – one private, one public. The private one is home-centred, mostly performed by women reading Panchali for the welfare of the members of her family or the widowed/elderly women, a type of solace at the thakur ghar (room for God). Most of the Bengali families have a thakur ghar in their residence; those who can afford it, otherwise the bedroom is converted temporarily into a thakur ghar. The other is collective like Durga Puja and pujas of many discovered Gods and Goddesses in public Pandals that engage people across age and gender, and this collectivity is more than and different from religion.

Fun-Loving Bengali

Apart from collective rituals, Bengalis are very fond of festivals like food festivals, picnics, get-togethers in the locality or organised at a distance. This may be discovered during the ‘Bengali season’ on the hills and seashore, the time being mostly October and December each year. They continue to speak in Bengali confidently even when they are in Uttarakhand in cent percent non-Bengali public area and search for Bengali food (Mach-Bhat) in restaurants. Most of them speak in laughable Hindi in the Hindi heartland when they think they know Hindi as an oral language.

Mother-centered Bengalis

The most pathetic condition is for the recently married boy of early thirties who gets sandwiched between his wife and mother, as he will have to appease both. ‘Mugdha Janani’ nourished the son who cannot be abandoned to the care or negligence of the new guest at home. Women enjoy natural power in the Bengali family very much, centred around the kitchen, so it becomes the power of both the wife and mother. This is a formal education neutral. The man hardly understands this power game.

Living in the Past

Bengali people, mostly elderly, continue to live in their past – they cannot leave the past, even if it was less materialistic by non-possession of white goods that were yet to be invented, like air conditioners and washing machines. They were rooted half a century ago, and many were forced to migrate from East Pakistan to West Bengal for the prize of independence that is the 1947 Partition. Some of the elderly people were willing to go back to their village in East Pakistan, the village that they considered as ‘Desh’ (country).

Accommodative Bengali

Bengalis cannot be finance-literate like Gujaratis or enterprising like the Punjabis. Religious fanaticism so far has not touched them, as may be evident from the absence of the post-1946 Riot in West Bengal despite provocations. Some districts like Murshidabad are inhabited mostly by the Muslim population, and not surprisingly, Hindus are perfectly safe there. Different caste groups co-exist who share tea in the same cup at a tea stall, and they are not bothered about who takes birth in what caste. Despite provocations in Manu tradition, casteism is socially distanced in West Bengal, other than pre-election instigation by a political wing.

New Generation Bengali

The new generation Bengali is an altogether different category that is ideology-neutral, that is fast in technique and technology, mobile and individualistic. This generation is the effect of nuclear families, and hence, the costs and benefits of living in ‘Ekannovorty Parivar (joint families) are not experienced. The new generation of Bengali post-2000 in the age below 45 in 2025, that is precisely those who took birth post-1980, are scattered over metropolitan cities in India and abroad for education and jobs. Most of them are thinly built and carry most of the time laptop-mobile phone-iPad. Many of them, till late thirties, are ‘double income-no kids’ (DINK).

Superiority

Once, Gopal Krishna Gokhale said, ‘What Bengal thinks today, India thinks tomorrow’. Thinking of carrying forward the society, of course, was there in Vidyasagar-Rammohun-Subhas-Rabindranath Tagore-Vivekananda-Aurobindo Ghosh-Sharat Chandra-Tara Shankar- Amartya Sen…. That day is gone. Now that superiority is in ‘Adda’ in a tea stall with random opinions about what world leaders should do concerning Gaza-Palestine, Russia-Ukraine, Trump-Putin telephonic conversation and the like. Still, Bengalis think they are superior to the people of the rest of India. This is difficult to swallow for Bengali people in general are much less ‘finance-literate’ than are the Gujaratis, much less enterprising, as are the people of Punjab, much less physically fit relative to people in Haryana and Bihar and so on. One indicator of superiority, maybe, subject to acknowledgement from the non-Bengali, is the ‘Babu’ or ‘Bhadra Lok’ identity of the Bengali, which means cultured. I abstain from discussing the issue because it is sensitive and comparative, if not with a touch of parochialism.

Narcissism

One extreme form of perceived superiority of the Bengali is narcissism – self-pride rather than understanding the base or cause. This often led to the silent development of inferior ideas about others like Bihari and Marwaris, which is on the wane of course. Bengali is a peculiar tribe that is cocooned within – often it thinks it is the only tribe or the leader tribe. It is self-glorification.

Radical and Reactionary Bengali

Bengali stands on extremes – one is radicalism-protest, and the other is status quo or privileged. Long back, Bengalis used to be bureaucrats-teachers-doctors. Of late, they are scattered and culturally distanced as very few scientists who search for the scope to leave the country for better options in research jobs in advanced countries, and the majority have no option but to live in a low-level trap. One offshoot of radicalism was the emergence of a political society with highly opinionated people as voters.

Dual Bengali

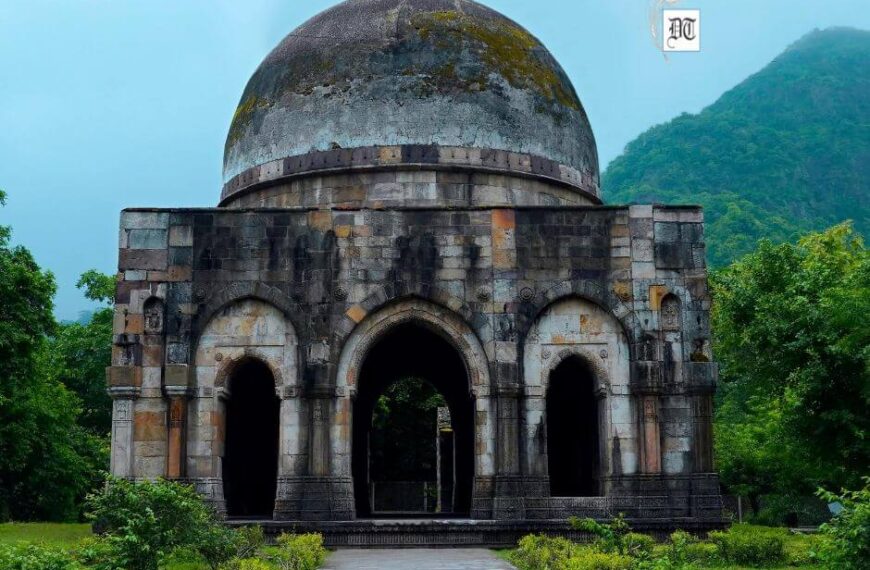

Among many classifications, one is dual existence of Bengali – one refugee, the other settled or non-refugee, the former migrated from East Pakistan post-1947 and post-1971 (from Bangladesh) and the other, original inhabitants of West Bengal. Cultural assimilation took a natural time by marriage, education, jobs, etc. Unity in diversity was reflected in the emergence of two major football clubs, namely East Bengal and Mohan Bagan.

The other duality is in the co-existence of ‘pravasi’ Bengali and settled Bengali, the former is united in the self-initiated linguistic group but not cocooned like the Bengali of Jamshedpur in the state of Jharkhand, Allahabad in the state of Uttar Pradesh, Rourkela in the state of Odisha.

Atmoghati Bengali

Living cocooned in the past, pride and repetitively glorifying it without any acknowledgement of what is happening in the rest of the world may be a disaster for the settled Bengali. Taking pride in what Bengali is not another problem – he is non-enterprising and often in the habit of belittling others. He is being gradually distanced from positions in public administration. For the past few decades, wisdom has been defeated in the hands of the lumpen. The wise gentlemen are underground or in fear. The political society has mortgaged civil society to hooligans. The civil society is in ‘atanka’ (deep fear). The other is crab behaviour, particularly among the middle section, which promotes unfair competition that does not lift people from the bottom layer. Both education and health suffocate in Bengal now. Some have left, and some are planning to leave West Bengal for better living. Escapism ruins West Bengal further. Absence of regular employment that could have been a possibility through the setting up of industries is another issue apart from the lock-out of sunset industries like Jute Mills on both sides of the Ganga that agonised the Bengali. Bengali political society that swallowed the cultural society reflected why Bengali is seen as Atmoghati (self-destructive).

Concluding Remarks

There are infinite words to get Bengali undescribed – what it is not. In describing, it is a mongrel – no single unit of analysis can describe it fully – it is a linguistic category, a cultural category, a ‘babu’ category, a brave category, a feminine category. It is an artist-painter-poet-singer-sculptor-scientist-teacher-philosopher. It is Rabindranath-Michael-Aurobindo-Vivekananda-Vidyasagar-Mahasweta-Amartya. It is ‘sabjanta’ (knows all) in the local tea stall. It is in football-rasgulla-Hilsa-Prawn. It is in a film and a coffee house. It is radicalism.

I doubt if any other linguistic community in the world has produced so many variations in a single language – the development of literature for literature and not for politics-films-business. Once, Shakespeare and the Bible were considered assets of British national wealth. Once, Rabindranath Tagore was the Bengali asset. There was a British sunset post-Second World War. Bengali sunset?

Appendix

Untold History that Exists

Bengali is a prominent one, probably among many tribes, who exists because of oral tradition, embedded in local literature and songs, a significant contribution of unknown women in shaping the history, a significant contribution of boatmen and the tourist guides who are considered less educated and all that. People in many work domains also had an unrecorded history like that of the workers in tea gardens.

Remaining untold or unrecorded, it becomes difficult to test the truth of what many people share post-independence in public places like tea stalls and the Coffee House in Kolkata, which remains vibrant culturally.

Methodology: Participatory and Disguised Observations at several locations at home and abroad.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By