Akash explores Mithras, Horus, and Krishna, unlocking their cosmic parallels and cultural divergences, which reveal the profound, universal language of myth, for Different Truths.

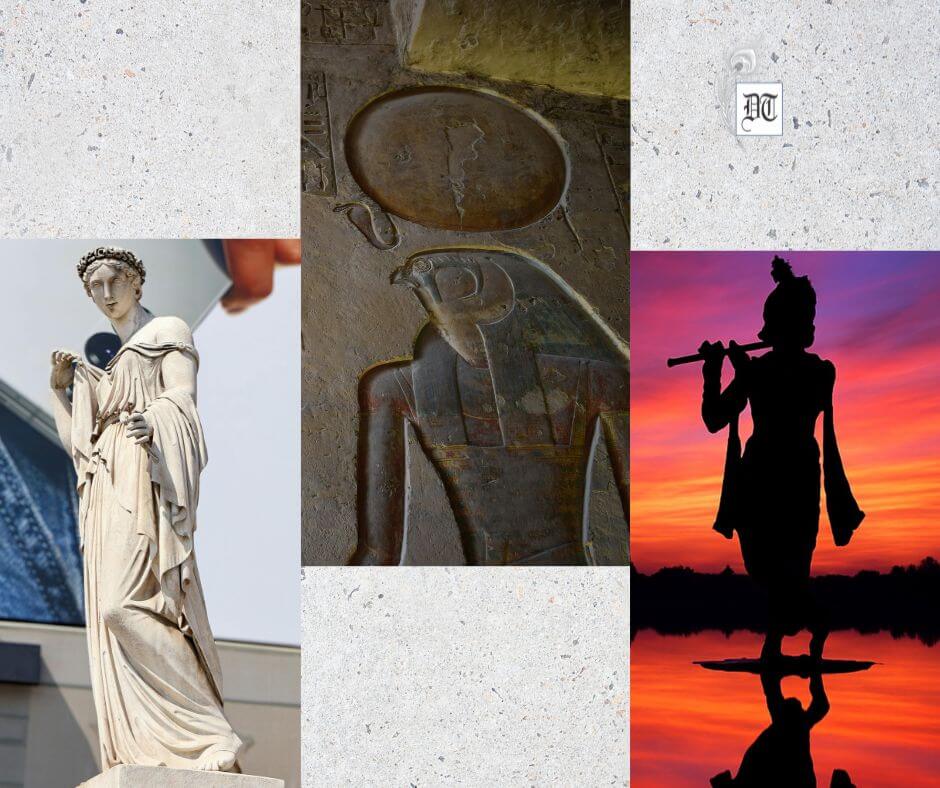

Religious traditions often evolve in conversation with one another. Across time, cultures borrow, reshape, reinterpret, and sometimes completely transform earlier mythological motifs. Because of this, certain divine figures in world religions share apparent similarities despite emerging from very different cultural and geographical contexts. Among such figures, Mithras from the Greco-Roman and Indo-Iranian worlds, Horus from ancient Egypt, and Krishna from the Hindu tradition of India are frequently compared—sometimes in serious scholarship, sometimes in pseudo-historical speculation. To understand where true parallels exist and where superficial comparisons mislead, it is essential to approach these three figures with care, nuance, and cultural sensitivity. This article provides a comparative study that examines the origins, symbolic functions, and reasons behind their sometimes-striking thematic similarities.

Origins and Cultural Contexts

Any comparative analysis must begin with a firm sense of origin. These three figures come from civilisations separated by thousands of miles and, in some cases, thousands of years. Yet each plays a vital role in the religious consciousness of the cultures that produced them.

Mithras

Mithras, or Mithra in an earlier Persian form, originated in the Indo-Iranian religious tradition. In the ancient Vedic texts of India, Mitra is associated with truth, contracts, and friendship. In Zoroastrianism, Mithra becomes a divine judge, associated with covenants, the rising sun, and cosmic order. However, the Mithras who appears in the Roman Empire from the first century CE onwards is not the same. Roman Mithraism, or the Mithraic Mysteries, developed into a secretive initiatory cult popular among soldiers and imperial officials. This version emphasised Mithras as a divine hero who slays a primordial bull to sustain creation. The cult operated in underground temples and offered salvation through initiation rather than public worship.

Horus

Horus is one of the oldest gods in Egyptian religion, appearing as early as Predynastic times. Over the centuries, the figure of Horus developed multiple forms, including Horus the Elder, a sky god, and Horus the Child, also called Harpocrates by the Greeks. Most famously, Horus is the son of Isis and Osiris, conceived after the murder of Osiris by his brother Set. Horus becomes the avenger of his father and the rightful heir to the throne of Egypt. He also symbolises kingship, protection, and the cyclical renewal of order over chaos. Egyptian kings were considered earthly manifestations of Horus, linking the god to political legitimacy and cosmic balance.

Krishna

Krishna emerges from ancient Indian religious literature, particularly the Bhagavata Purana, the Mahabharata, and various regional traditions. He is an avatar of Vishnu, the preserver god of the Hindu Trimurti. Krishna’s origins blend pastoral folklore, theological speculation, and epic heroism. He appears as a mischievous divine child, a romantic flute-player, a wise king, and ultimately the supreme deity who teaches the Bhagavad Gita to Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. His birth, life, and teachings form a foundational part of Hindu spirituality and devotional (bhakti) tradition.

With origins established, we can begin comparing these figures more directly, paying attention to genuine parallels rather than forced or fabricated ones.

Common Themes and Symbolic Roles

Though culturally specific, these deities share several thematic and symbolic motifs that have drawn the attention of scholars.

1. Divine Births and Sacred Childhood Narratives

Birth and childhood narratives often serve to establish a deity’s identity and mission. In the case of Mithras, Horus, and Krishna, the circumstances of their births carry symbolic weight.

Mithras is said in Roman iconography to be born from a rock—petra genetrix—often depicted emerging fully grown, sometimes with a torch or dagger. This miraculous birth sets him apart from humanity and underscores his role as a cosmic saviour figure.

Horus the Child is hidden by his mother, Isis, in the marshes of the Nile Delta to protect him from Set, who had murdered his father Osiris. His infancy becomes a period of vulnerability but also magical protection, as Isis uses spells and divine intervention to keep him safe.

Krishna, likewise, is born under royal persecution. The tyrant Kamsa seeks to kill him because prophecy foretells that Krishna will be his destroyer. Krishna is secretly transported across the Yamuna River to be raised in a pastoral village, protected by adoptive parents.

These narratives share the motif of a divine child threatened by evil forces. The motif might not indicate historical borrowing but instead reflects a widespread mythic pattern: the vulnerable infant who represents hope against tyranny or chaos.

2. Cosmic or Moral Combat

Another similarity lies in each deity’s role in combating evil or restoring order.

Mithras performs the foundational act of slaying the cosmic bull. This bull-slaying (tauroctony) symbolises the release of life-giving forces: grain, animals, and cosmic vitality. Though the exact interpretation remains debated, scholars generally view it as a myth of cosmic order.

Horus engages in a prolonged struggle against Set, the god of chaos and desert storms. Their conflict represents the eternal battle between order and disorder, and Horus’s victories symbolise the rightful succession of kingship and the restoration of harmony.

Krishna fights numerous demons throughout his youth and ultimately plays a central role in the Kurukshetra War. In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna defines righteousness (dharma) and instructs Arjuna to fight against injustice. He becomes the moral compass of the epic, guiding humanity toward ethical conduct.

The thematic similarity is clear: each figure participates in a cosmic or moral struggle, defining the structure of the universe or society. Yet their battles differ in tone and religious significance. Mithras’s act is cosmic and mythic; Horus’s is political and dynastic; Krishna’s is ethical and philosophical.

3. Symbolic Association with Light or the Sun

The symbolism of light is common across cultures and appears in all three traditions.

Mithras is strongly associated with solar imagery in the Roman period. He is often paired with Sol Invictus, the unconquered sun. Initiation rites are possibly aligned with solar cycles.

Horus, especially as the sky god, is linked with the sun and the moon. His eyes represent these celestial bodies, and the daily journey of the sun across the sky is sometimes interpreted as the movement of Horus.

Krishna is less directly solar, yet he is associated with divine radiance. In the Gita, his cosmic form shines brighter than a thousand suns. His skin is traditionally depicted as dark blue, representing the infinite sky.

The solar or light symbolism functions differently but contributes to each deity’s association with cosmic clarity, power, and transcendence.

4. Themes of Salvation and Divine Favour

Though the forms differ, all three gods play roles in spiritual salvation or divine favour.

Mithraic worship promised initiates some form of salvation or ascension. The precise content remains poorly documented, but inscriptions and temple art suggest a path toward immortal life or cosmic harmony.

Horus provided protection, especially for the king and for the dead. His eyes, the “Eye of Horus,” were powerful amulets for healing and safeguarding.

Krishna offers explicit spiritual liberation (moksha). In the Gita, he states that surrendering to him frees one from the cycle of birth and death. Devotional worship to Krishna remains one of the most popular paths to salvation in Hinduism.

While Mithras and Horus offer more worldly or symbolic salvation, Krishna provides a clear doctrinal path to liberation. Nonetheless, all three embody the idea that the divine interacts with human destiny in a transformative way.

Important Differences and the Risk of Oversimplification

Comparisons must be made carefully. Some modern writers, particularly those seeking to challenge established religions, have exaggerated parallels between Mithras, Horus, and Krishna, claiming identical birthdates, identical miracle stories, or identical crucifixion narratives. These claims do not hold up under scholarly scrutiny.

1. Distinct Cultural Evolution

The Indo-Iranian roots of Mithra have almost nothing in common with Egyptian cosmic mythology or Hindu devotional theology. The similarities often arise from universal archetypes rather than direct cultural borrowing.

2. Divergent Functions

Mithras in the Roman world is an initiatory figure tied to military cohesion. Horus is political and symbolic of kingship. Krishna is profoundly theological, philosophical, and emotional, inspiring devotional communities.

3. Historical Separation

Chronologically, Horus is the oldest, emerging well before 3000 BCE. Mithraic worship appears thousands of years later. Krishna’s traditions coalesce between the first millennium BCE and the early centuries CE. There is minimal direct influence between these cultures, and in many cases, it is unlikely.

Possible Points of Cultural Interaction

Although direct borrowing remains uncertain, subtle cultural interactions are possible.

Indo-Iranian peoples migrated widely, so early versions of Mitra may have travelled across cultures.

The Greeks and Romans, who had some contact with Egypt, introduced reinterpretations of Horus as Harpocrates.

The spread of Hellenistic culture after Alexander the Great created new zones of exchange between India, Persia, and the Mediterranean.

Still, these interactions more often produced reinterpretations rather than direct adoption of myths.

The Deeper Reason for Similarities: Universal Mythic Patterns

Joseph Campbell and other scholars argue that many mythic patterns recur across cultures because human psychology produces similar stories to explain life’s mysteries. The divine child, the cosmic hero fighting evil, the solar deity, and the saviour figure appear from Mesoamerica to East Asia. This suggests that the similarities between Mithras, Horus, and Krishna may reflect shared cognitive and social needs rather than shared historical origins.

These needs include:

· a desire for protection from cosmic or earthly chaos

· Reverence for solar cycles is crucial to agriculture

· fascination with miraculous births representing hope

· longing for divine guidance or salvation

Such universal concerns naturally produce recurring motifs.

Conclusion

Mithras, Horus, and Krishna are compelling figures whose stories, though distinct, reveal humanity’s enduring fascination with the divine. Their similarities—miraculous births, battles against evil, associations with cosmic order, and roles as guardians or saviours reflect recurring patterns in myth and religious imagination. Their differences—cultural context, theological depth, symbolic role, and historical development are just as significant, reminding us that similarity does not imply sameness.

Mithras belongs to a mystery religion rooted in Indo-Iranian ideas but transformed within the Roman Empire. Horus reflects Egypt’s concern with kingship, order, and the annual struggle against chaos. Krishna embodies the devotional heart of Hindu spirituality, offering ethical wisdom, divine love, and spiritual liberation.

Understanding these figures side-by-side enriches our knowledge of ancient religions and illuminates the universal human quest to understand the cosmos, morality, and the divine. The comparison offers no proof of direct borrowing but rather insight into the shared mythic vocabulary of humankind. Through their stories, we can appreciate both the diversity of human religious expression and the deep unity underlying our collective imagination.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

Akash Paul, a renowned criminologist, theologian, and demonologist, and the author of two globally acclaimed textbooks, pioneered post-crime analysis in criminology and comparative religious studies in theology. His expertise spans criminal profiling, sexual offenses, Christianity, and religious history, with notable contributions to each of these fields. An insightful critic of contemporary society, he also writes poetry, short stories, and novels, blending creativity with profound societal analysis.

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Excellent article son…. 🍫

A outstanding religious article with divine presence 😌💕💕💕💕✨✨