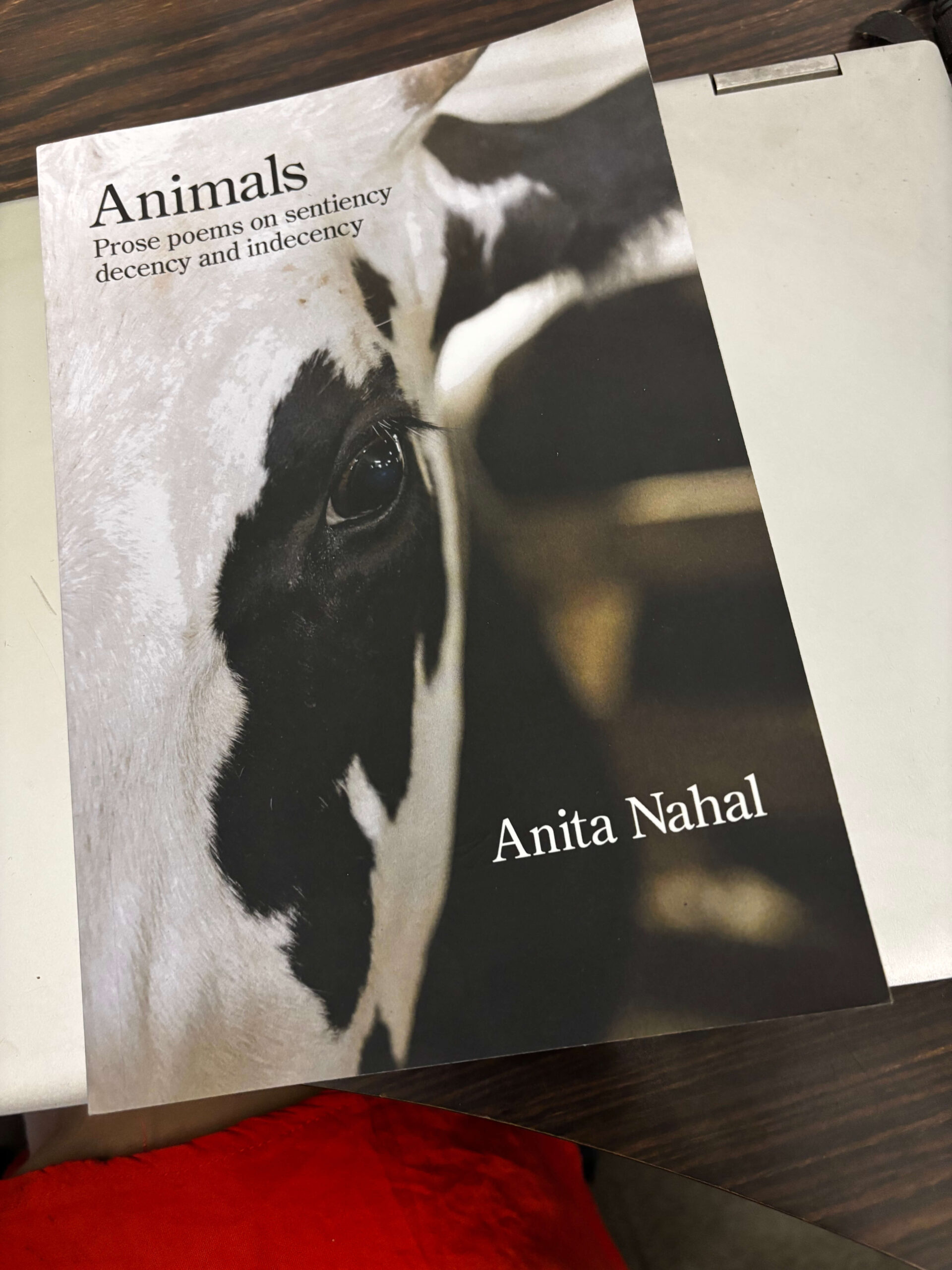

Prof Sanjukta introduces Anita Nahal’s Animals: Prose poems on sentiency, decency and indecency, a poignant critique of human-led animal exploitation for DifferentTruths.com

AI Summary

- Human Brutality: The collection exposes the systemic abuse, neglect, and “barbaric” exploitation of animals across domestic and public spheres.

- Voice for the Voiceless: Nahal utilises prose poetry to articulate the silent agony of sentient beings trapped in labs, zoos, and industries.

- Universal Empathy: The book equates the suffering of animals with vulnerable humans, urging a global shift toward non-violent, conscious co-existence.

Keywords:

Animal rights, Anita Nahal, Prof Sanjukta Dasgupta, prose poetry, sentient beings, animal cruelty, Anthropocene, speciesism, animal welfare, human-animal bond

Animals have been represented as dynamic walkie-talkie figures in ancient myths, epics, fables and oral narratives. Before the blast of the Industrial Age and its promise of development, in the agricultural economy, proximity between animals and humans was axiomatic. There were ducks in the ponds, hens in the backyards, dogs and cats roaming through the localities, and cows and goats in the sheds. Urbanisation and the lure of skilled work and improved lifestyle led to the flourishing of nuclear households. Trapped in small flats, humans still desired pets as companions. On a rather strikingly different note of pain, protest and empathy, Anita Nahal’s forty-one prose poems in her latest book of poems, Animals, address the unabated suffering and neglect of animals in the 21st century, both in the public spaces and within the domestic walls. Nahal states that the exploitation and oppression of animals by humans seems to have become a callous, barbaric practice.

So, in her introduction, Nahal unequivocally writes, “Herein lies the essence of my poems: to remind us that all living beings are sentient. The only difference is that animals cannot express themselves in a language we understand. The look in their eyes, their shudders, their running away from us, the hiding, the barking, and even wounding us are all their ways of telling us to leave them alone.” Expectedly, in the first prose poem, Nahal raises a series of rhetorical questions: “Who really are the animals? Do we even want that word in dictionaries anymore? Beasts, brutes, and creatures are synonymous, filled to the dirtiest rims of conscious limbs. Who are we and they? Who are the animals?”

Interestingly, while many religions regard animals as God’s creations, not all regard them as divine beings. The Hindu religion regards monkeys, elephants and cows as sacred. In Chinese spirituality, the dragon is a mythic symbol of power and prosperity. The cat and jackal were revered in ancient Egyptian religious practices. Animism has been an integral part of indigenous cultures, where birds, snakes, turtles and many other animals have been linked to divinity. Industrialisation and urbanisation have relegated animals to zoos and sanctuaries. Moreover, the poet makes a bid for consciousness-raising as she writes about stray animals that roam everywhere and domestic pets that are either excessively pampered or abused or are subjected to a mix of both, depending on the domestic environment and the mood of the inmates at that particular time.

Predatory animals are also noticed by the poet. In the poem ‘Wolf’, Nahal expresses her annoyance as she writes, “an innocent young wolf… Photographed just before. Just before it was shot between the eyes. Like it was a dirty wooden board for practicing bullseye.” In the poem ‘Mulesing’, Nahal uses gruesome, ghastly signifiers that code human brutality towards helpless animals, in this case, sheep. Nahal states with undisguised sarcasm, ‘You wear your Merino proudly,’ while she records the visual horror of mutilating a sheep, ‘Executioner style, the sheep is hurled against the wall… Sounds followed, of striking the wall – smashing, splitting, breaking – and a shriek.’ The riveting poem, ‘Gandhi, Gus and Anew’, negotiates cultures and geographies, the digital ecosystem, as ‘Gandhi’s tears fall on his deer-like nose’. The poem of protest and imploration, ‘Please don’t foster me’, records the callous neglect of dogs within the foster homes: ‘I am chained sometimes too, and I cry for freedom.’

The poet, however, links the sadistic, ruthless similarities in behavioural practices of humans towards weaker, helpless humans, not just helpless animals. The vulnerabilities of the powerless and the violence of the powerful resonate in the deliberate reiteration of the monosyllabic word, ‘small’ in the line, ‘Sometimes we might kill a small snake, or squash a small fly, or a small mosquito, a small bee, a small cockroach, or a small spider.’ So, in the poem ‘Survival of the fittest or sheer inconvenience’, humans and animals are equated in their zeal to survive, by hook or crook. Expectedly, in the poem ‘Zoo’, Nahal states that in her adulthood, zoos seemed to underscore entrapment. So, she writes, ‘We too live in zoos. In many zoos, like Matryoshka dolls, they are tightly stacked and confined. The universe, the Milky Way, the Earth, continents, countries, cities, homes, rooms. Some are compassionate in their zoos, some not.’

Inevitably, following the poem is ‘Sadism’, which is an outcry, ‘Why have a pet dog if hitting, throwing, and pummeling are all that you know? All that you do…’. Also, the poem ‘Blood bank’ disturbs readers, as the poem, written in the first person, voices the agony of a dog which has been trapped in a laboratory as a blood donor. The ailing, emaciated, half-fed animals are uncared for, and the dogs no longer wag their tails. ‘This is where I and my fellow mates are punctured with needles frequently.’ The accusatory voice of the poet seems to rise in protest as the canine inmate asks. “They say our blood will help others of our kind… Do humans who donate blood live alone in cages till they die? Bonded blood for the free.’ In the first person, too, the donkey narrates the indifference of the people it ferries uphill and downhill. Sightseers and tourists use the donkeys in order to visit cultural and religious sites in remote areas. The donkey matter-of-factly narrates its feelings about human indifference and self-absorption: “And I will continue to be ridden by countless souls satiating their desire or thrills to climb a mountain, pay abeyance, or enjoy a setting sun.”

Anita Nahal’s prose poems in Animals code expressions of pain, anger, outrage and resignation, as she repeatedly foregrounds the need for human empathy for the animal world, which is an integral part of the planet. The hideous violence of bullfights, the brutality of hunting and deep-sea fishing, and the indifference towards pets are all represented by the poet, with the purposeful agenda of asking fellow human beings to sensitise themselves towards the helpless animals who are unable to vocalise their torturous plight in the era of the Anthropocene.

In her introduction to these deep protest poems, Anita Nahal states that her poems are intended as an awareness campaign about the ‘inhumane activities to which animals are sometimes subjected by addressing some of the major issues of global animal rights, such as general neglect and cruelty, animal testing, animals in sports, hunting and races, animal abandonment, animals in fashion, animals in the blood bank, encroachment of animals’ lands, ivory trade, and pollution of waters and forests, to name a few.’ Anita Nahal’s Animals, an engrossing slim book of 60 pages, demands the attention of empathetic readers so that the animal world can co-exist with the human world in a non-violent environment where each sentient being matters.

Cover image sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By