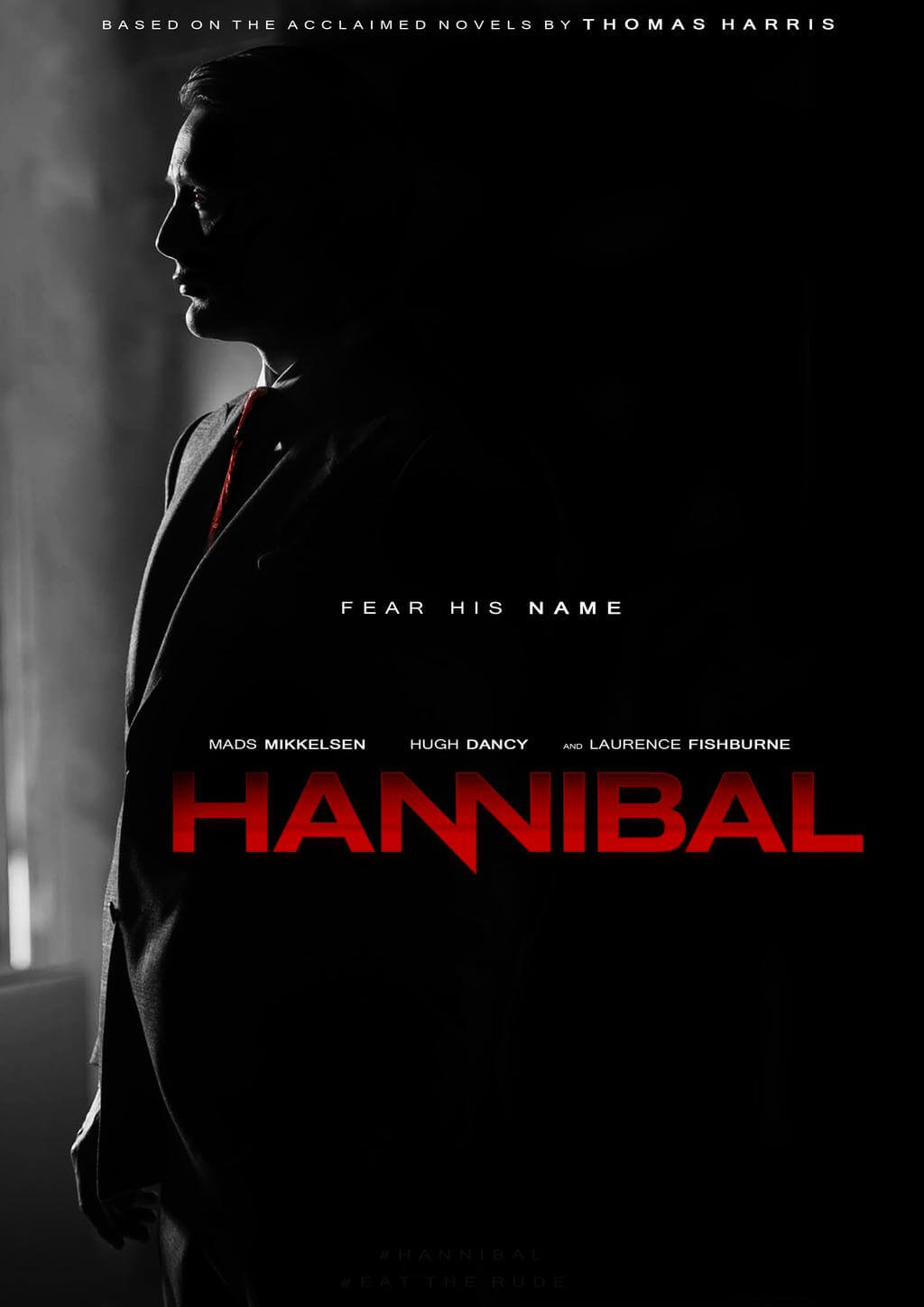

Akash revisits NBC’s Hannibal, a philosophical descent into darkness, where art, intellect, and murder converge. A powerful exploration of Hannibal Lecter’s deadly philosophy, exclusively for Different Truths.

NBC’s Hannibal (2013), created by Bryan Fuller, reimagines the infamous Dr Hannibal Lecter, not merely as a cannibalistic serial killer but as a sophisticated philosopher of death, art, and the human condition. As a forensic psychiatrist, Hannibal operates within society, yet outside all its moral frameworks. His actions, although criminal, are not impulsive or sadistic; rather, they are meticulously composed acts of aesthetic rebellion and existential assertion. He is the Nietzschean Übermensch cloaked in fine tailoring and culinary excellence, with each murder serving as an expression of his transcendent worldview.

This paper aims to delve into the philosophical core of Hannibal Lecter as portrayed in the TV series, uncovering a tapestry of Nietzschean ethics, aestheticism, amorality, psychoanalysis, and philosophical seduction. Through an analysis of Lecter’s relationships, behaviours, and spoken insights, we explore how Hannibal elevates serial murder into a metaphysical discourse on what it means to be human or god.

Nietzschean Roots: The Übermensch Ideal

Dr Hannibal Lecter exemplifies Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch, or “Superman,” a being who transcends the herd morality of society to create his values. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche calls for the rise of individuals who dare to reject Christian morality and shape the world through their will to power. Hannibal does precisely this, but in a disturbingly literal way. His declaration, “Killing must feel good to God too. He does it all the time. And are we not created in His image?” reflects his self-identification with divine agency. Hannibal assumes a godlike posture, not one of benevolence, but of creative destruction.

Rather than adhering to societal norms, Hannibal believes morality is an illusion designed for the weak. His violence is not driven by malice but by a sovereign aesthetic and philosophical impulse. Like Nietzsche’s Übermensch, he lives “beyond good and evil,” forging his code. He chooses his victims based on elaborate internal judgments—rudeness, ignorance, vulgarity, traits he deems beneath the dignity of existence.

Nietzsche warns of nihilism in the absence of divine moral order. Hannibal not only embraces this nihilism but repurposes it. He becomes a creator of meaning through violence, revelling in the existential vacuum with operatic flair. His killings are less about dominance and more about narrative: the assertion that life, in its raw, unfiltered form, is governed by chaos, and he is the only one brave enough to give that chaos a name and a face.

Thus, Hannibal is a living philosophical paradox, one who abhors mediocrity and worships transformation. Through blood and bone, he redefines humanity on his terms. In the Nietzschean spirit, he becomes both prophet and executioner, conjuring a new order from the ruins of the old.

Aesthetics of Murder: Beauty, Art, and Death

One of the most striking aspects of Hannibal is the sheer beauty of its horror. Each act of violence orchestrated by Lecter is composed like a painting, a symphony of flesh, light, and silence. In Season 2, the infamous human mural constructed from dozens of corpses sewn into a colour wheel is emblematic of his aesthetic philosophy. Murder, for Hannibal, is an act of creation, not destruction.

This philosophy echoes the late 19th-century doctrine of Aestheticism, championed by figures like Oscar Wilde and Walter Pater, which emphasised “art for art’s sake.” As Wilde wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written.” Hannibal extends this to life itself. There are no moral or immoral murders, only elegant or inelegant ones.

Walter Pater’s notion that life should be lived as a work of art is taken to macabre extremes. Hannibal’s cuisine, often prepared from his victims, is a double-layered aesthetic statement: beauty in presentation, horror in implication. His artistry serves not merely to satisfy but to elevate; death becomes a medium, flesh a canvas.

Through this lens, murder is sanctified, not to an end, but an end. The brutality is disguised beneath layers of etiquette and refinement, echoing the paradox Wilde lived and died by: that beneath beauty lies decay, and decay, perhaps a higher beauty.

Ultimately, Hannibal performs murder as theatre. Each scene is framed, lit, and scored with intent. The audience, be it Will Graham or the viewer, is seduced not just by Hannibal’s intellect, but by the terrifying thought that death can be divine. Beauty, in his hands, is not innocent. It is predatory.

Amorality and Antisocial Morality

Contrary to the caricature of serial killers as deranged or chaotic, Hannibal Lecter is a man of principle, just not those that society recognises. He is not a sadist. He kills not out of hatred, revenge, or rage, but curiosity, precision, and artistry. This detachment places him outside the realm of conventional ethics and into the domain of moral nihilism.

In Albert Camus’s The Stranger, Meursault is condemned not for murder but for failing to express socially expected emotions. Similarly, Hannibal violates not just legal codes but emotional ones. His crimes are dispassionate, performed with surgical objectivity and grace. His morality is internally constructed, rendering him a figure of existential amorality.

He aligns, too, with Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, who tests whether extraordinary men are bound by laws made for ordinary people. Hannibal believes himself to be one such man—above guilt, beyond judgment. He views the justice system as a construct built on fear, not truth.

In his world, morality is not an absolute but a consensus: a consensus he never agreed to. His calm demeanour in the face of cruelty is not psychopathy in the clinical sense, but a form of radical philosophical protest: “I let you know me. See me. I gave you a rare gift, but you didn’t want it.”

Hannibal doesn’t deny morality. He simply finds it unnecessary. The result is a character who cannot be measured by good and evil, but by influence, beauty, and transformation.

Psychoanalysis and the Inner Labyrinth

As both psychiatrist and manipulator, Hannibal Lecter navigates the human psyche with unsettling ease. He is the very embodiment of Freud’s unconscious, unleashed, instinct given elegance. Through his therapeutic sessions, Lecter delves into the subconscious of others not to heal but to provoke, to liberate repressed darkness.

Freud’s model of the psyche—Id, Ego, and Superego–is masterfully inverted in Lecter. He is the Id cloaked in the Superego, primal drives disguised beneath intellect and order. For Will Graham, Lecter functions as a psychic mirror, one that doesn’t reflect, but refracts.

Lacan’s “mirror stage” posits that identity is formed through misrecognition; what one sees is never quite what one is. Hannibal destabilises Will’s identity, making him question whether the empathy he wields is a gift or a curse. Hannibal doesn’t merely manipulate; he reconstructs.

Psychologically, Hannibal is not just an analyst; he is a surgeon of the soul. His therapy sessions are philosophical trials where he tests the boundaries of identity, morality, and self-awareness. Bedelia Du Maurier, his therapist, notes, “He will always be in control.”

Hannibal functions as the Other in Lacanian terms, a gaze that renders the self uncanny. His intimacy feels like an invasion. He penetrates psychological defences not with violence, but conversation, silences, and shared meals.

This duality of healer and destroyer makes him one of fiction’s most profound psychological constructs. He reveals the fragility of self, the lie of control, and the terrifying truth that reason is not our master, but our mask.

God Complex and Apotheosis

Hannibal Lecter does not merely act as a man; he acts as a god. His frequent theological metaphors— “Killing must feel good to God too” are not hyperbole but confessions. Hannibal sees himself as divine: a sculptor of fate, a demiurge of destiny.

In classical mythology, hubris is the fatal flaw of mortals who dare rival the gods. Prometheus, punished for bringing fire to humanity, and Oedipus, undone by prophecy, both echo through Lecter’s narrative. However, unlike them, Hannibal does not fall. He ascends.

Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy describes the Apollonian and Dionysian: order and chaos, form and ecstasy. Hannibal embodies both. He is composed and chaotic, surgical and sensual, all at once. In this synthesis, he surpasses human duality and becomes mythic.

His God complex is not rooted in narcissism but artistry. Gods, in Hannibal’s theology, do not judge; they create, and creation sometimes demands destruction.

His murders are often symbolic executions, corrective sacrifices in a world that is too mundane to matter. By killing, he asserts order, not legal order, but aesthetic and moral order that he alone discerns.

He arranges lives, manipulates fate, and orchestrates revelations. His victims do not merely die; they are transformed. Even Will Graham is shaped by Hannibal’s designs, not murdered, but re-forged.

Thus, Hannibal’s apotheosis is complete. He becomes not a god of light or justice, but of shadows and becoming. A divine artisan whose sacrament is death, and whose cathedral is the human mind.

Relationship with Will Graham: Ethics of Influence and Becoming

Among Hannibal’s most profound philosophical engagements is his relationship with Will Graham. Their bond is not rooted in friendship but in transformation, a Hegelian dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Hannibal sees in Will a fragmented soul ripe for reconstruction.

Throughout the series, Hannibal serves as the midwife to Will’s becoming. He pushes him to embrace his darker instincts, insisting that empathy is not weakness but raw material for rebirth. He tells Will, “You are becoming.” This is not a threat but an invitation.

In Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, consciousness evolves through encounters with its opposite. Will’s struggle against Hannibal ultimately reveals his potential for monstrosity. Hannibal, in turn, yearns for affirmation of his worldview that morality is mutable, that humanity is a canvas.

Their relationship is mirrored in the mimetic theory of René Girard, where desire is contagious and rivals become doubles. Hannibal desires not Will’s affection but his transformation. He doesn’t want to kill Will; he wants Will to choose to kill, thereby validating Hannibal’s ontology.

This seduction is philosophical, not sexual. Hannibal offers not comfort, but clarity: a vision of a world where guilt is redundant and instinct is sacred. For Hannibal, Will is the ultimate art project, the final movement of a symphony played in blood and whispers.

Their final embrace in Season 3 is not reconciliation, but recognition: two beings beyond salvation, locked in a dance of becoming. It is, perhaps, the most honest moment has ever lived.

Conclusion: Philosophy of Horror and Humanity

Dr. Hannibal Lecter is more than a fictional serial killer. He is a philosophical archetype: a challenge to morality, identity, and civilisation itself. His actions are governed not by impulse but by a deeply reasoned, albeit horrifying, metaphysical system. Through the aesthetics of murder, Nietzschean ethics, and psychological seduction, Hannibal becomes a mirror held up to our collective unconscious.

Hannibal (2013) is not a story of good versus evil but of form versus chaos, godhood versus humanity. Lecter stands not as a warning, but perhaps as a prophecy: of what happens when intellect is severed from empathy, and beauty is divorced from conscience.

His philosophy, like his cuisine, is exquisite and revolting. It forces us to ask: What if evil is not ugly? What if it is articulate, composed, and charming? Hannibal Lecter smiles as we ask these questions because we’ve already begun to see the world through his eyes.

Picture credit IMDb

By

By

Very interesting article 💖✨🖊️💖✨

Awesome article, son.

Comprehensive, well-structured and very well expressed.