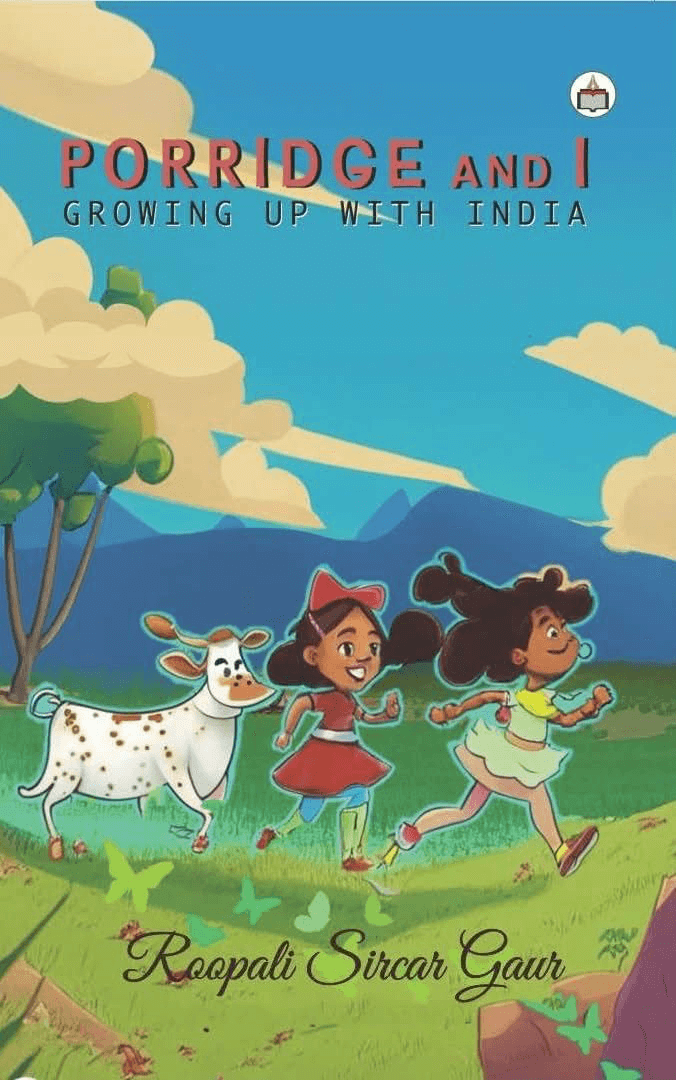

Emmie reviews Porridge and I: Growing Up with India, which offers a child’s eye view of postcolonial India, blending innocence with cultural and political awakening, exclusively for Different Truths.

In the book, Porridge and I: Growing up with India, Dr Roopali Sircar Gaur takes us into the world of children – A world that is both universal and yet particular. It is one full of both fantasies and fears, loyalties and rivalries, exploration and retreat. All lived out concerning the significant adults around them. The universal nature of the experience of childhood means that this book can speak to a very wide readership. Certainly, I found strong resonances with my childhood.

Yet, at the same time, each child grows up in a particular culture, moment of history and in a domestic setting that is peculiar to them. For Sircar Gaur, the overriding arc is that of India’s newly won independence from colonial rule, as experienced by Porridge and her younger sister. Within that theme, others interweave – an exploration of what it is to be considered truly ‘Indian,’ tradition versus modernity, the role of women, the tragedy of war, and issues of sexuality and sexual abuse. But this is no dry socio-political commentary. Nor is it a memoir of an adult reflecting on their childhood. Instead, the author leads us into a world seen and experienced through the eyes, ears, and thought processes of a child, one which she brings brilliantly to life using creative and imaginative language. It makes for rich and enjoyable reading.

“Miss Doris is English. That is why her skin is so white.” In the simple structure of those opening sentences, we know immediately we are in the mind of a child. One who is the narrator. Descriptive scenes pay close attention to detail, as seen through a child’s eye. What adult would notice a glow worm sleeping near the tree trunk throne – and comment, “ I think it is dreaming.” Children have a marvellous aptitude for noticing the unseen.

Incidents are accepted at face value and simply recounted to mother without any thought of the implications involved – for example, Maggie dancing naked in the kitchen. Elsewhere, the mysteries of life are speculated upon between the sisters, such as discussions arising from attending Father Dudley’s church with Miss Doris. So typical of childhood.

The author’s use of descriptive language – whether of people or of landscapes – brings out the perception and language of children. As the family relocate from the soft landscape of the Blue Mountains, the narrator comments, “We are off to where the desert burns like the fire in the chullah in the Cook House built in 1856.” The two sisters then live in a deserted palace where, we are told, “snakesneak across to the house and curl up under cosy cool pillows. Flying snakes whoosh fly from one end to the other” Those words brilliantly describe the inhospitable world they now inhabit. But those two phrases, ‘sneaksnake’ and ‘whoosh-fly’ used here as verbs, are good examples of how Roopali’s writing is both creative and yet so typical of a child’s eye-view of the world.

Then there is the personification of mischief – the fat green horned creature who slides over the schoolroom windowsill and sits alongside the younger sister, who remains anonymous throughout. It is the archetypical childhood scenario, projecting the cause of trouble elsewhere. “It’s not my fault – it was he that made me!” But that naughtiness makes the narrator more real – and likeable

All the above, I believe, are deliberate ploys on the part of the author to cleverly take us into the world of childhood. For Porridge and her sister, it is a world that is fast emerging from centuries of imperial rule. As the story unfolds, the ’cook house built in 1856’ – first encountered on p17 – provides a recurring motif which helps to carry us through the story. Maybe because of its association with the departure of the British, or maybe because it provided a stable point of reference for the children in a life that was fast-changing. Or maybe both …

Miss Doris – the governess is a major player in the life of ‘Porridge’ and her young sister. In today’s world, one can only flinch at the cultural arrogance with which she denies the girl her Indian heritage and dubs her ‘Porridge.’ A name that is accepted and used throughout the book until the closing paragraph, when her proper name, her Indian name, is joyfully and powerfully reclaimed.

Yet the early childhood described is full of Englishness – 4 o’clock tea on the lawn, with Ovaltine and banana bread for the girls, dinner dances at the gymkhana club for ‘Mother and Daddy’ and English as the language of the family. “We are as English”, the younger sister comments at one point. Yet the father is strongly pro-Indian, having fought the British as part of the Underground movement to gain Indian independence,

The racism inherent in British imperialism is laid bare, as we see in the story told by ‘daddy’ (pp29-33) of the educated Indian who accepted the name ‘Shree Dog’ to find employment in the Indian office. It is telling, perhaps, that although the rest of the family found it amusing, we are told “Porridge didn’t laugh or smile.” What resentment, I wonder, smouldered there?

Thankfully, by the end of the book, there is a firm reassertion of Indian Independence, as the girls’ father answers the brash British sergeant, “The good old days, as you call them, are over. They were only for you goras, you white guys. I am an officer in the Indian army, which, as you are aware, is no longer the King’s army. Now it is the People’s army…I am free to wear anything I like in my own country.’ At that point in the text, I felt like cheering!

Throughout, there is a good exploration of family dynamics. Porridge is, perhaps, the typical ‘big sister’. Setting the agenda and expecting little sister to acquiesce with her plans – something she dreads, especially when forced to endure countless ‘‘vaksinations.” The mother is a constant presence in their lives, though it is interesting to note how her identity splits when her husband is away on long-term duty. These are times when she reclaims a more traditional Indian way of life. We are also privileged glimpses of her private journal reflecting on her life and the times, the joys and the sorrows.

That journalling feeds into a brief look at the role and status of women in this new world. Porridge and her sister witness weddings at which tearful brides are led away from the family home to be taken into a strange family. They actively encourage a young friend who is pledged in marriage to a boy far away to rebel against her fate. This she does, and the situation is remedied. A precursor of women’s liberation, maybe! Play activities, though, still fall into what is appropriate for boys and what is suitable for girls. Here again, though, we are shown the way forward when the narrator refuses to be typecast and wins admission to a boys’ gang, then discovers that she is expected to perform the caring duties of a female. She promptly rejects that stereotyping and deserts the gang.

Education – both formal and informal – is stressed as the way forward to achieve personal advancement, even for girls. The sisters, however, are not always happy with the arrangements. We are shown, too, examples of brave women standing firm in the face of danger, including their mother facing down marauding bandits. Women in post-imperial India are being shown the way forward. Though it must be admitted, many of the multitude of characters in this story cling to tradition.

There is so much else I could say about this book – so many rich seams to be mined – but word limits prevail. Yet I cannot finish without a brief reference to war. ‘Porridge and I’ is set in a time and location when “The enemy” is a very real presence. The skill and bravery of soldiery are mentioned, but so too is the dreadful human cost. The tragedy of warfare is brought home simply – and childlike – with the observation on both the honours and the battle scars of the returning soldiers.

My very last words, though, must come from the final page. India has moved from living in the shadow of its imperial past and into a world of its determination. Porridge is consigned to the past in a strong and powerful statement. “Didn’t you know?’ A voice boomed. “ My name is Parijat. I am the immortal Indian tree in Heaven, which blossoms flowers that look like stars. … India was now free.”

Dr Roopali Sircar Gaur is to be congratulated on writing such an enjoyable and lively book. One, I thoroughly enjoyed reading and heartily recommend it to all.

Cover image sourced from the author

By

By

By

By

By

By

Deeply impressive

Excellent review of this book “Emmie.” I would never realize how detailed and involved it is. Your review allows for its reading by adults, not only children. Thank you for the details.

Bless you! I hope all is well with you.

I have read this novel when it was being penned by Roopali, my wife, not once but many times over and I must admit this review by Ms Margaret Blake brings the soul and spirit of the work to life so clearly. The essence as brought by her is the world, as seen experienced and expressed through the eyes and mind of a child, transiting from colonialism to freedom. My deep appreciation to Ms Blake for this very profound review of the book.

Dear Pran.. I am humbled by your kind comments – and so pleased that my review is seen as being true to Roopali’s work. She i steh one who did an excellent job!

A fine review of a book I’m reading and planning to review: now Ms. Blake has made my chosen task even harder!!

Hi Azam… You will do a sterling job of your review – different ‘voices’ reveal different insights. Just enjoy the experience.

Excellent review. I believe I need to buy it and read it now. I will.

Immense gratitude Margaret ( Emmie) Blake for the in-depth reading and review of Porridge and I : Growing Up With India . Your understanding of colonial and post colonial history in India stands out. The child’s world peopled with adult talk

and the subtle nuances of a transforming India reflected in food and conversations and changing geographical spaces are so clearly marked in the review.

Thank you again.