Mehreen, writing for DifferentTruths.com, weaves a haunting tale of Dulal, a graveyard keeper whose life shifts from poverty to a mysterious mansion.

AI Summary

- Fateful Encounter: A young groundskeeper is “purchased” by a wealthy, guilt-ridden merchant who claims a divine vision led him to the boy.

- Luxury and Secrets: Dulal trades his ratty hut for silk and satin, only to discover his benefactor’s dark past and midnight cries.

- Cycle of Penance: The story explores the heavy price of atonement, where inherited wealth cannot easily erase the ghosts of former sins.

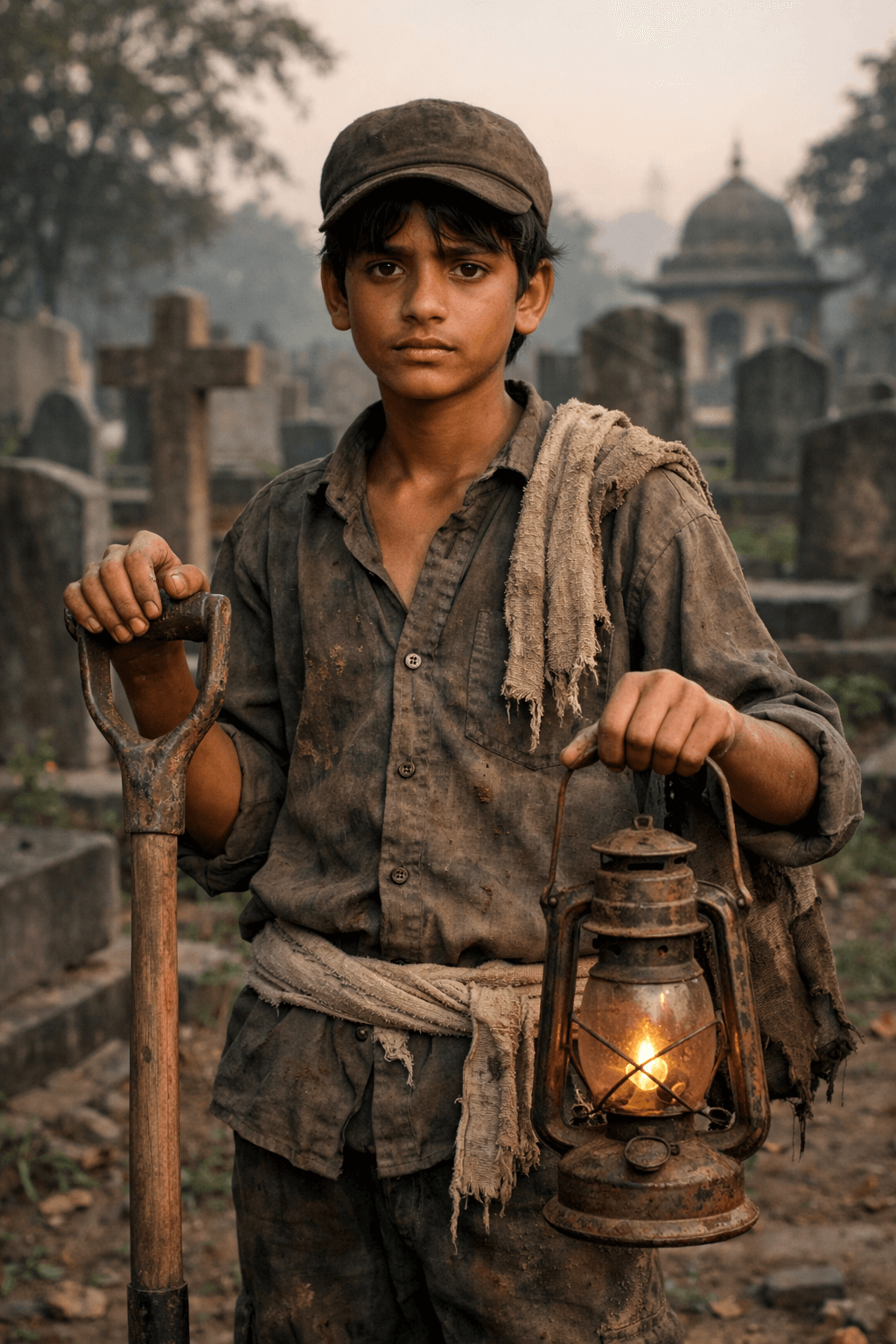

Fifteen-year-old Dulal gets off a rickshaw. A car edging out of a tight park, missing a near clash with the rickshaw-puller on the Purana (old) Dhaka’s heartbeat, narrow, crowded lane. A man sits in the black leather seat in a cream kurta and navy-blue pyjamas.

A groundskeeper, Dulal is in charge of a graveyard known as the Garden of Martyrs or Ganj-E-Shaheedan within a complex called Hussaini Dalan; a shrine built around the later half of the 17th century Mughal era—a Twelver Shi’ite Imambara, whose core belief is that twelve successors of Prophet Mohammad (Peace be upon him) are the spiritual and political leaders of the Islamic world. From Hazrat Ali (Peace be upon him) up to the Twelfth and the last occult Imam Mehdi, believed to return. The Twelver devotees commemorate the martyrdom of Hasan and Husain, two of the Twelvers killed in the battle of Karbala—the Grandsons of the Prophet Muhammad SM (Peace be upon him).

Garden of Martyrs entombs contributors and prominent figures of the Shi’ite community who assisted in the construction of the complex. This elaborate and ornate combination of Mughal and British structures, the Hussaini Dalan, is replete with many kanjuras rooflines, doric style columns, arched windows and doors is a specimen of a fine blend of Mughal art and architecture and the British at a later date. One of the building’s halls, called the Tazia Khana (House of Mourning) is a symbolic veneration of Hasan and Husain’s tombs.

The main building overlooks a pond. Dulan enters through the gates and runs along a path by the pond outside the complex toward the Garden of Martyrs. On his way, he sees a few boys playing hopscotch on the pond’s eastern ghat. The boys don’t see him, but Dulal’s face brightens up; he comes up to them, but they’re focussed on hopscotch, each waiting his turn to hop through the squares.

A few miles away from the Garden of Martyrs, another graveyard is situated. It is for the commoners where Dulal’s mother rests. Some graves are distinctly marked by trees growing straight out of a neighbour’s tomb without any tombstone epitaph, unmarked, while the Garden of Martyrs is better established and better cared for.

In this month of Muharram, this special month, frequent gatherings of the devotees in the Husssaini Dalan take place to signify and gratify the soul—month’s grieving period to cry for Hasan and Husain, the two Martyr brothers of the Karabala; Dulal’s groundskeeping must be top-notch, all neat and spruced up for visitors.

Graveyards are restful. Dulal knows from spending long hours here. He understands the depth of quietude; midnights excepted, when they come alive; skeletons perform a tango dance. Of once fleshy individuals below six feet, each of them gets out, twirls around wavering trees in the midnight breeze, nightbirds shriek in the folds of the palm leaves, jack fruits, banyans, healthy trees rooted into the ground, supping sustenance from the dead. Dulal prays to Mother’s grave when the world sleeps; he views the de-fleshed dances of the dead and yearns to transform to get ahead.

When the night ceases at sunrise, incessant vehicles’ honk from the graveyard’s periphery, the sounds seize the day as it were, and energise the place from a state of slumber. Rickshaws often pull up and jostle around lamp posts painted with sporadic betel juice. Where rickshaw-wallahs sit on rubble, chatting around uncovered drains and open garbage dumps, eating a dry chapati sometimes near the chapati-maker’s hot street stove. While women comb each other’s hair, picking out lice occasionally midst hovering flies.

Troubles crop up easily for them, such street-dweller like, undeterred blood flow in the veins, governments’ prop up policies to eradicate poverty and homeless crisis. Commoners’ graveyard is a ghetto of homelessness, while cleansing poverty may not be actually agenda-driven, such clean-ups from time to time in the name of rehabilitation make the government look progressive in the media. Inevitably, such efforts put the poor out, shoving them from one makeshift pavement across another, where streets continue to be dwellings, and the ceaseless sky, the ultimate roof over their heads.

Same story but varied locations—the streets of Hussaini Dalan aren’t any exception—this impressive Imambara, where gatherings are the largest in this month of Muharram, praying and crying for Imam Hasan and Imam Husain, a little girl sits under the ornate gates. Her uncombed, matted hair is tied up in a pigtail; she screams out for food. Her plea falls on deaf ears, unnoticed by the food-stall owners; the imposing Hussaini Dalan juxtaposed against the smallness of such street girls and boys, men and women, reducing them to a spec! Even those playing on the pond ghat remain invisible to most, frozen in time—a habitual feature of this place and people, which remains forever, unchangeable.

Dulal feels short-changed by his meagre salary. Although he realises that it’s better than being unemployed, his father is a cleaner in the Hussaini Dalal, polishing the mosaic floors to a shine every morning, afternoon and evening. At nightfall, Father and Son return to a ratty hut outside the thick walls of the complex, eat a plain dinner of rice and daal, and sleep on a floor bed of a single torn mattress.

Hut’s thin walls don’t keep neighbours’ snores out, keep Dulal awake, but in these moments, he also dreams of becoming. Prayers at his Mother’s grave at midnight keep him warm within his fuzzy dreams. When he returns in the early hours, he takes his place to catch up on sleep beside his father on the mattress; fast asleep, breathing booze, Dulal’s small chest tightens in pain, and screams silently—‘Oh! Why? Why? Why must you drink?’

Mornings bring them the same dreary chores. This morning, however, Dulal’s father sees a man crying in the far end of the Tazia Khana. Crying is not uncommon in the month of Muharram. But this man cries not, ‘Ya Hasan,’ ‘Ya Husain,’ he cries aloud for forgiveness. The cleaner leaves him in peace as he exits the room. He sees Dulal playing on the pond ghat. He beckons him to come. Father hands him some money to buy him a paan from the paan shop outside the big gates. With Dulal, the crying man also departs, walking abreast to him. The man stares at Dulal and draws him into a conversation.

Father’s face distorts, and he winces and doubles up in pain on the floor. He loses sight of them. In a while, Dulal comes back with paan and places it on Father’s palm. He sits by him and pats his back.

“What did the man ask you, Son?” Father asks.

“Nothing,” Dulal answers.

“I saw you two talking.”

After a pause and hesitantly, scratching his forehead, Dulal replies.

“About my belly-button, my name and where I live and if I live alone.”

“Why?” Father asks.

“I don’t know. Anyway, I have to go,” he says.

“Did you tell him where we live?” Father asks.

“Yes,” Dulal answers.

The cleaner stands up and puts the paan into his mouth. A deep frown appears between his brows. Dulal reports back to duty in the graveyard. The inconsequential day passes. Back in the hut at night, Father cooks rice and some daal again. In the firelight, they sit on the mud floor on a cane mat and scoop out some rice from a hot pot on the stove. Dulal pours himself a glass of water from a pitcher beside the stove. They hear a smack of the hut door opening, someone pushing in. Both Dulal and Father stare in shock when they see the man from the Tazia Khana entering their shabby den.

“You? I saw you in the Tazia Khana this morning, you’re in mourning,” Father says.

“Yes, yes, I was there this morning, grieving and repenting,” the man says.

“What brings you here? How can we help?” Father asks.

“My name is Mahdi Dewaan, I’m a merchant, a perfume seller.”

“I can’t buy any perfume,” Father says.

“No need to buy anything. However, I will buy something from you. You have the one thing, I don’t have,” he says.

“Which is?”

“Your son, you have him.”

Mahdi looks at Dulal and smiles.

“You want to buy my son? Why?” Father asked.

“I’m childless. Only he can help me out of my grief.”

“Why him? There are many orphanages in the town, and lots of orphans walk our streets every day. You can have anyone. No, my son isn’t for sale. I have nothing besides him. So no, please go,” Father says.

Dulal looks on aghast, hearing this unbelievable conversation where his yearning to become something is almost happening. This man, his saviour, can emancipate him from this dark life, and Father says, “No?” If he goes with him, he can get Father’s help too, for his treatment, the pain and whatnot.

Mahdi continues, “I saw visions of him, your son, they say I must have him, him only, and no other.”

“I don’t care about your visions or these crazy lies.”

Father says, slapping a fly on his wrist.

“Except, it’s not a lie. Your son has a birthmark around his belly button like a halo, right?

He is the chosen one; God’s decision has already been made. Your son’s destiny to live on that cliff mansion has been granted. God’s will, I’ve come to take him.”

“Still, he’s mine; I can’t let you have him.”

Mahdi smiles, “You may have fathered him, but are you his fate-maker? Can you write his destiny?”

Father’s face distorts in pain; he begins to double up again; he lies on the floor. Mahdi quickly goes outside and summons his men to carry him, and asks Dulal to follow him to his car. Parked near a paan shop, Dulal recognises the car from a few days back, from a near collision with his rickshaw. Mahdi’s men put Father in the back seat, and he seats Dulal between them in the middle, then shuts the door. Coachmen bring the car out of a not-so-tight spot.

It’s a long, about half-hour ride to the mansion. On the way, Dulal sees a blue restaurant named “Ant Kitchen,” and then a few meters away, a grouping of shops called “The Pig Bazaar,” strange names, Dulal thinks.

They arrive in his mansion up a steep cliff. Mahdi holds Dulal’s hand, pulls him stiffly and instructs his men to take Father to some “Red Room.” They whisk him away.

“Stop, where are they taking Father?” Dulal asks.

“From tonight, this moment, I’m your Father, you call me Father, okay?”

“But, but…’

Dulal’s jaw drops.

“No buts, just come along now. My servants will show you the room next to mine in the mansion.”

Mahdi disappears, leaving Dulal in the big hall of heavy oil paintings hanging on the walls. One housekeeper takes him to his new room. With the man’s help, Dulal gets into a ready perfumed bath before his arrival. Afterwards, he changes into silk pyjamas. A massive bed with satin bedclothes waits for him. He sleeps like never before. In the morning, a proper breakfast of eggs and toast is served in bed, a far cry of one dry bread in the shack. Overnight, he feels like a priceless prince.

After breakfast, he asks the housekeeper waiting on him, again, ‘Where’s Father?’

The man replies, “He’s having breakfast in bed, next door.”

“No, I mean, Father, my Father.’’

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand,” he says.

Dulal begins to scream at the top of his voice, dream or no dream, he wants to know where his real father is. At this point, the man bows and leaves him. Dulal hears a click of the door locking on the other side. He has questions, where is his new Mother then? So far, he only sees men in this mansion, no women. He gets out of bed and knocks on the door. Someone opens it, and he slips out of the room in his silk pyjamas. He sees Mahdi coming out from the next room.

“You’re upset?” Mahdi asks.

“Yes, I want to know where Father is.”

“One isn’t enough, you want two? Aren’t you happy with all this?” Mahdi asks.

“I’m. All this is really nice, but I want to know that Father is safe too.”

“Your Father is in rehab, undergoing treatment. You can visit him if you like. But be mindful that the choice is yours, all this can be yours one day and then your children, private education, unlike your public one,” Mahdi says.

“Okay, as long as Father is happy and in good health.”

“He’ll be healthy soon if he gets off cheap alcohol. You can ask him yourself if he is happier being here, instead of that dirty shack,” Mahdi says.

Dulal knows better not to negotiate. He knows the other world only too well. In the year, he gets to see Father one day. This fairytale state is more than what he can ask for, but it is also common knowledge in the mansion that the boy’s real father is a cleaner from the Hussaini Dalan, to everyone’s envy, who will inherit it all when Mahdi passes.

Dulal tries to understand why Mahdi must atone for his sins. What’re they? Why is marriage not his thing? However, Dulal is not allowed to see his real father again, after his first visit; nor does he see any Mother of any sort or any woman in the mansion. Dulal concludes that this must be a man’s only mansion where no woman has ever had an entry, perhaps, besides Mahdi’s mother, whose oil painting hangs in the hall.

His curiosity piques. He raises questions and hears whispers in the shadows of the great hall, without much success. Does a scandal blight his reputation so that no woman agrees to marry him? Dulal enters Mahdi’s room secretly one morning when he is out. Still in his silk pyjamas, he tiptoes to the next room and knocks on the door. He hears nothing. Gingerly, he opens the door, and he gets in. In the empty room, he smells a faint scent. He walks over to the window and doesn’t hear the door opening behind him. He hears a voice, ‘Dulal.’

Dulal startles and turns around to find Mahdi towering over him. He cowers and runs to a corner. A chill runs through him.

“What do you need to know? Just ask, okay? Mahdi says.

“This gives Dulal some strength.

“Oh! Sorry Father! I didn’t mean to be rude.”

“Speak up!” Mahdi says.

“This scent…”

“What about it? It’s musk, male deer secrete this long-lasting scent, which I trade worldwide. Its use is also strongly recommended in our religion,” Mahdi says.

“You cry at night, and I hear lashes.”

“Maybe, close your window, then,” Mahdi grimaces.

“I could, but I’m curious.”

“Ah! Here we go, curious, and truth shall set you free?”

“Maybe.”

“Okay, shall we sit then?” Mahdi asks.

They sit on the edge of Mahdi’s big bed. Side by side.

“On one of my hunting expeditions, one afternoon, I went to a forest. In the waning evening light, I spot a white-bellied deer around a shaded swamp bowered by filtered leaves of trees; a shot from my gun kills the deer. However, in the crosshairs, I also see a young man running behind the deer. I make a rash decision, I choose wrongly, I either take the shot or risk losing the prey. When the deer falls, it does so on the man’s waist down, stuck under it, in my arrogance, I blame him, and I’m glad that my prey doesn’t get away—cold isn’t it? Boastful about the kill when the severely injured man lying under with severed limbs, breathing shallow, on death’s door, I convince myself that he isn’t my responsibility. We walk away, leaving the man gasping for breath on the edge of the dark swamp.”

Mahdi pauses and inhales a sharp breath.

“A few months on, something totally unrelated happens. With each day passing by, I begin to see how my money and power blind me; I start to get nightmares, sweats and fevers. A sickness invades my body. I become emotionally dysfunctional, unable to sleep or feel happy; relationships don’t last, and I don’t marry. I begin to feel afraid, and I hear voices. A friend suggests penance and repentance. Repent, I start to get visions, I see strangers in my vision, then I see you one night and keep on seeing you over many nights, and a halo around your belly-button—a birth mark of yours?” Mahdi stops.

“What happened to the man?” Dulal asks.

“I don’t know. I haven’t found him in any hospital or rehab, I searched for him, God knows, I’ve tried.”

Mahdi stops talking and goes into a trance.

“Yet you continue to repent even after all your penance for taking me in. Why? You didn’t try hard enough? Is he dead? After all, he’s your mess, the one you hurt badly and now you don’t even know what’s happened to him? Then you snatch me from Father. You buy me with these trappings, the less fortunate? No?”

“My visions are directly connected to you, somehow, I don’t know how? What’s more? A male deer secretes musk to attract female deer during breeding season, when the musk sac is most active—a callous, brutal act of removing the musk sac by killing the male deer. I’ve hunted many… payback time… this is payback… although, I’ve moved on, stopped my hunts, my penance is not done… ties me to all the wanton killings at mating time…a game…a game…I did it not just for perfume but also for sport.

“Dulal nods. “You’re guilty as hell. I hope you’re on medication.”

“I’m,” Mahdi says.

Dulal’s curiosity pans out, but he doesn’t feel any better, let alone free Mahdi from the ghosts of his mind. Somehow, he knows that these bequests of inheritance can’t purge his guilt any time soon.

Eight years on, Dulal grows up into a full man. He finds himself a kind wife, Fatima, a local village girl and a skilled cook. In the next few years, his two sons are born, whom she raises diligently in the mansion, also cooks and cares for Mahdi, the repentant man.

Nevertheless, on black moonless nights, Dulal still hears Mahdi’s cries of atonement from the whips. One day, he cries out loud, a name, Mahfuza, I’m sorry, please forgive me, I’ve tried to give you a child, but I couldn’t. You died childless, unhappy; dead people can’t forgive. As a grown man, Dulal now has some inkling of a state of confinement in Mahdi’s inability to father a child or to make this woman named, Mahfuza, Mother.

While Dulal continues to take flowers to his mother’s grave at midnight, he talks to her through the tree which grew in her grave; about randomness, his fanciful fate, and Mahdi’s sordid predicament, which his stony mother only listens, neither judges, nor tries to pry—the leaves tremble, and leads Dulal to see silken ribbon tails in the sky, floundering, then melting into the oblivion of a star in the novice hands of a random kite-runner.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

Mehreen Ahmed is an Australian novelist born in Bangladesh. Her novel, The Pacifist, was a Drunken Druid Editor’s Choice in 2018. She has published eleven books and stories online. Her most recent works are in BlazeVox, The Bombay Review, Phenomenal Literature, Kitaab, Cabinet of the Heed, and Boudin.

By

By

By

By