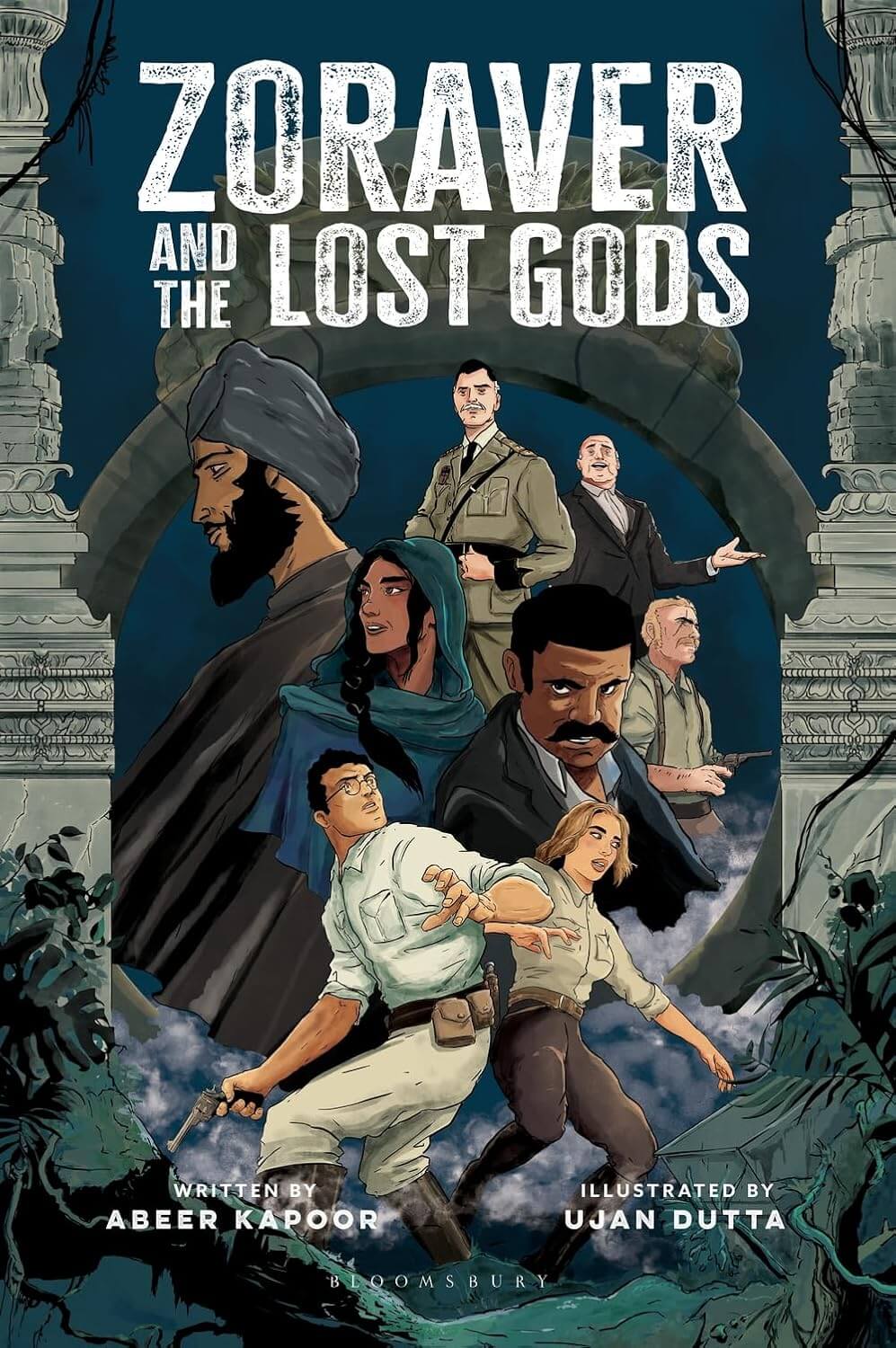

In this thrilling heritage thriller, Zoraver and the Lost Gods, a Cambridge student battles British spies to save India’s ancient secrets, reviewed by Dr Gill for Different Truths.

AI Summary

- Zoraver Khan uncovers colonial intrigue as the Raj’s devious “Department of the Reclamation of Wealth” loots India’s timeless treasures like the Ring of the Lost Gods.

- Weaving history, spies, nationalists, and Ashoka’s Navaratna secrets, the novel echoes Kipling’s Kim with twists, astrology, and resistance societies.

- Action-packed prose delivers suspenseful, counterfactual twists on greed and heritage, primed for sequels or TV adaptation.

Zoraver and the Lost Gods, an exhilarating novel written by Abeer Kumar and illustrated by Ujan Dutta, was published in 2025 by Bloomsbury. Zoraver’s distinctive identity notwithstanding, its illustrious pedigree is traceable to Rudyard Kipling and TN Murari.

Kipling’s Kim came out in 1901, and TN Murari’s distinguished sequel, The Imperial Agent, came out in 1987. Both novels are as exciting as they are thought-provoking, grounded in history from 1901 to the eve of India’s partition and independence. Murari boldly shepherded Kipling to continue Kim’s character development under the pressures of his English ancestry, vagrancy in the streets of Lahore, the intelligence bureau’s grooming, and the dilemma of clashing ideologies of Independence and Partition.

Zoraver’s active timeline on the eve of the First World War is close to that of Kim. Abeer Kumar adroitly deals with the unbridled greed driving the East India Company (EIC) and Crown Rule. William Dalrymple’s Anarchy, a history of the EIC, cherishes the same theme. It opens with the irony of the Indian word loot, appropriated and enacted by the EIC with moral alacrity and single-minded ruthlessness, refined and delivered to Crown Rule after the failed 1857 Revolt.

Zoraver laudably wields prose and plot structure to make its point without recourse to dealing a victim card. Devoid of subjective adjectives or attributes, the narrative engenders a refreshing liberty in the reader to adjust the story within a chosen moral framework, if so desired.

On its own, Zoraver is a riveting story, plaited with twist after twist, surprise after surprise, instigating guesswork, which delightfully fails! The Department of the Reclamation of Wealth, also called the Secret Committee, is not a moral binary but a colonial conspiracy to launder ill-gotten gains through English Common Law imposed on an un-English land.

The Raj’s Department of the Reclamation of Wealth, headquartered in Fort William, Kolkata, runs a network of scholars, spies, renegades and sepoys to find and appropriate timeless Indian treasures and secret knowledge. To reclaim is to recover that which was lost, yet the Raj feels fit to claim as a loss what it never owned and then ship it out of India to a damp island.

After all, the greatest collection of Indian treasures remains the private museum of Powis Castle, Robert Clive’s UK estate, filled with the knighted clerk’s booty.

Zoraver’s action-packed ingredients consist of overlapping and competing Raj agencies and Indian secret societies resisting the British with discreet sophistication in a race to acquire the secret knowledge embedded in the Ring of the Lost Gods of King Ajatashatru.

Yet, there is resistance: the Society of Indian Historians is a “quasi-nationalist group that often dealt with anachronisms, legends and rumours…headed by Kishanlal Khatri.” Jugantar, a secret group, is ready to fight the Raj.

Abeer Kumar expertly weaves within the fabric of the story the legend of the Third BC Emperor Ashoka, confiding secret knowledge to the Navayana, a select group of nine. The narrative informs that “… he (Ashoka) told them to find ways to protect the wealth by scattering it and hiding the records so that no one could fall prey to such avarice. The practice continued for a millennium, from the Guptas to the Mughals, who helped the Navayana keep the secrets.”

They are also known as Navaratna, or nine gems, referring to an arrangement of gemstones representing celestial influences in Vedic astrology. Ashoka’s Navaratna was revived and appropriated by Mughal Emperor Akbar and later, in 1923, by Talbot Mundy in his novel The Nine Unknown. Lately, the Nine have made their appearance in the writings of Clive Cussler, Christopher C. Doyle, Shobha Nihalani and the TV series Heroes. It is believed that they continue to exist.

Inserted into wheels within wheels, multi-dimensional characters constantly astound.

Gloria Clive, a double agent, was mentored into the Department of the Reclamation of Wealth by a French viscount. Kishanlal Khatri and Benson Isaac risk their lives to deliver a letter written by the astrologer, Himmat, to his grandson, Zoraver Khan, a “Cambridge man”. The characters of Pankaj from the Majlis, Hayworth Cornwallis, Deputy Head of the Secret Committee, and Jahaj Singh, security officer, are ensconced in onion skins.

Active and evoked historical characters entwine with the fictional and bespeak credibility: Dadabhai Naoroji, General Dyer, Cunningham, Warren Hastings, Antoine Polier, his collector of art and artefacts, archaeologist Charles Masson, Nawab Munna Jan of Namak Haram Haveli and King Ajatashatru.

King Ajatashatru of Magadha, East India (405 to 373 BCE), committed parricide to seize the throne. He was a contemporary of Mahavira and Gautama Buddha, villainised in Gore Vidal’s 1981 novel, Creation. Vidal, though, missed out on Ajatashatru’s redemption of parricide and divine forgiveness, dexterously reprised by Abeer Kumar through the Ring of the Lost Gods, which selectively talks based on possession being nine points of the law.

As in Edgar Allan Poe’s fiction, embodied objects and places acquire the weight of functioning characters with distinctive personalities. Zoraver shows doors blasted open, visions, dreams, curses and intersecting planetary influences which come to life and assume personalities in the astounding world created by Abeer Kumar.

Places like the astronomy and astrology complex of the Oudh kingdom’s Taronwali Kothi, Rohilkhand, Harappa, portals of ancient temples, coded seals and India’s Naksha shawls of secrets encoded into embroidery swirl in Zoraver’s addictive magic cauldron.

The interweaving of astrology and charts complements the timeline of the story.

Destiny, stars, constellations, coincidences, and double agents play their parts with alacrity.

Zoraver highlights ignorance and opportunistic confidence trickery by illustration. An old pipkin is flogged as an antique, just as Amanda Holden buys a milking pail as a birthing bucket in the Indian Artefacts episode of Goodness Gracious Me.

Sophisticated, meticulous structure and an absence of verbiage unravel the plot with controlled efficiency, without relying on artifice. Appearances and assurances are deceptive, yet the orchestration of secret lives conjures a series of Russian dolls to juggle suspense, clarity and twists!

Zoraver progresses at a brisk pace, without ceding to the temptations of irrelevancies, tangents or digressions. Right from the beginning, the historical collaboration of Mir Jaffar and the Marwari Jaggat Seths, who initiated the crime and reaped its harvest, sets the moral tempo.

And the climax is a geopolitical surprise at its most pragmatic, raising a tornado of counterfactual continuity at the disposal of the author’s genius.

Counterfactual, or alternative history, is divided into two subgenres.

Upward counterfactual writing offers a blueprint of how the situation could have been better to avoid the chain reactions that led to its undesirable consequences — improvement, in search of excellence, by avoiding future mistakes.

Downward counterfactual fiction is about how the situation could have been worse, reducing dissatisfaction with how it was handled, lowering expectations and influencing a more positive view of the actual outcome.

Zoraver and the Lost Gods seems to be tailor-made for several sequels and should make a riveting TV series. It would be interesting to see which direction Kumar decides to steer the succeeding episodes of Zorawar Khan’s adventures as the Cambridge man and his allies handle the Raj’s misadventures while India churns to its sovereign destiny.

References

1. Zoraver and the Lost Gods, written by Abeer Kumar, illustrated by Ujan Dutta https://www.bloomsbury.com/in/zoraver-and-the-lost-gods-9789354353536/ https://www.amazon.in/Zoraver-Lost-Gods-Ujan-Dutta/dp/9354352790?s=bazaar

2. Goodness Gracious Me https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zSLpF7t3evk

3. Kim, by Rudyard Kipling

4. The Imperial Agent, by TN Murari

5. The Nine Unknown, by Talbot Mundy

6. Shadow Tyrants by Clive Cussler and Boyd Morrison

7. The Mahabharata Secret, by Christopher C. Doyle

8. Finders, Keepers, by Sapan Saxena

9. Nine, by Shobha Nihalani

Cover photo sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By