Aditya argues: unlock why human subjectivity trumps AI: Dive into philosophy’s timeless debate on consciousness, reality, and the irreplaceable ‘I’ that machines can’t replicate, for Different Truths.

There can’t be an objective reality outside, as we can’t come out of our biological selves and see things. If there is an objective reality also, we can’t know it without our individual subjective selves. If we say something is there, it can’t escape from our subjective interpretation. And this is also central to the “hard problem of consciousness” (Chalmers, 1995). The current neuro-philosophy also supports that the objective reality (if it is there) can’t be known outside our biological self.

Historically, subjectivity and objectivity have been discussed by scholars and philosophers across the world. And I would state here that it is the subjectivity that makes us human and distinguishes us from machines. So far, no one can have subjectivity except humans on Earth. At least we can say that we don’t know yet if anyone other than humans has subjectivity. I can say it is human-specific and human-born. And probably it has been an evolved one. When I say this, I also mean that non-human and non-living things like machines may not have subjectivity. The “I” in AI is not Descartes’s Cogito.

Descartes’s Cogito

Descartes’s cogito is very much human. René Descartes, one of the forerunners of the Enlightenment, gives importance to human subjectivity. His first principle, “Cogito, Ergo Sum (I think, therefore I am)”, determines the existence of human subjects as the foundation of scientific knowledge. It is not that subjectivity was not discussed before Descartes, but Descartes’s method was a departure from the traditional notion of subjectivity in Western philosophy.

Do things exist independent of our perception? Yes, states Immanuel Kant. Kant says the world we see is not the world as it is but as it appears to us to be. Our mind is the active agent for experiencing the world. We can never have direct knowledge of things outside our cognition. For Kant, there are two worlds: 1) Noumenal, 2) Phenomenal. The noumenal world is things in themselves, independent of our cognition, and the phenomenal is as things appear to us. It means we know the world within a limitation we can’t go beyond.

This phenomenal world is highly subjective, as it is limited to our beliefs, desires, opinions, values and so on and so forth. In the book Being No One, philosopher Metzinger states that the content of subjective experience is the content of an integrated, global process of reality-modelling taking place in a virtual window of presence constructed by the human brain (Metzinger, 2003: 215). We can’t have direct access to reality. Biologically, it is impossible, and whatever we see is through a seeing. Whatever we hear is through a hearing, and whatever we feel is through a feeling. This is why there may be a thought that a machine can do the same; it can simulate reality. Whatever it may be, our world is based on human lived experiences that a machine can’t have.

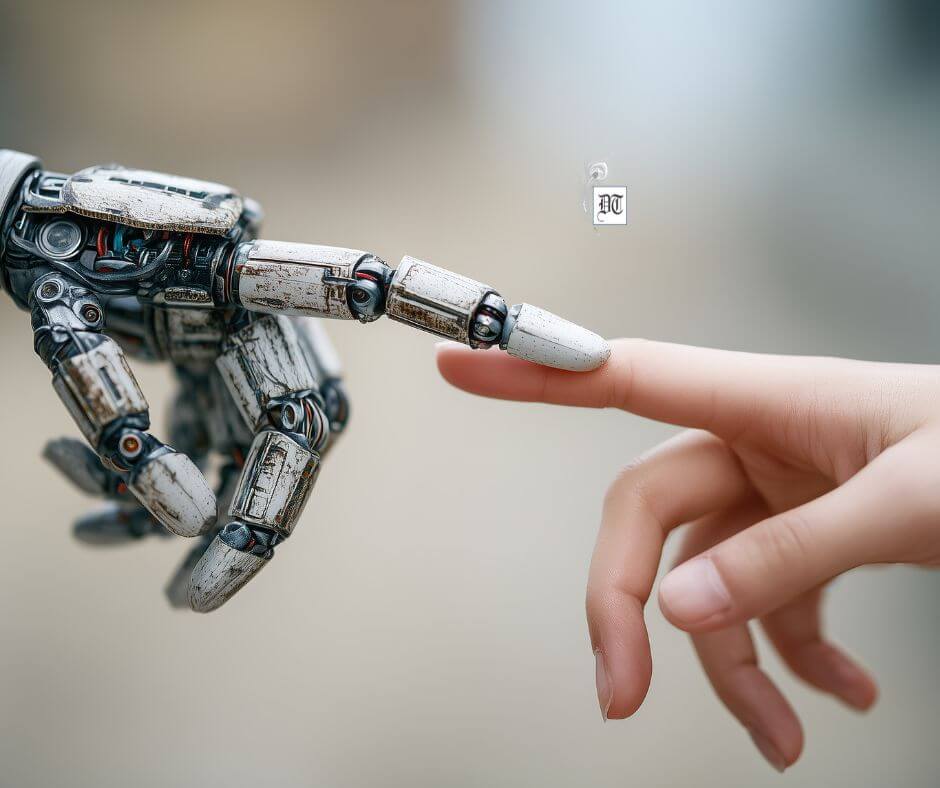

Man, Machine and AI

These days, thoughts are around man and machine and the replacement of humans with AI. Out of curiosity, I asked a question to Google Gemini. I asked, “Can you have subjectivity?” It answered, “The short answer is no, I do not have subjectivity in the human sense. The longer, more nuanced explanation is that my ‘existence’ is fundamentally different from a human’s. And Gemini listed down a list of explanations regarding why it can’t have subjectivity:

A. I don’t have personal experiences or a “self.

B. I don’t have emotions, feelings, or opinions.

C. My “perspective” is an emergent property of my training data, not a personal one.

D. I don’t have a body or a physical location.

These differentiate a human from an AI Assistant. If human subjectivity includes the above experiential phenomena, then no machine can replace humans unless they are made humans. It further says it’s a tool designed to process and generate information. It’s a machine based on algorithms and logic. Humans are not machines, though they have some machine-like features. The same question was asked to Copilot – the AI Assistant from Microsoft – and the answers are interesting:

I can simulate subjectivity—beautifully, convincingly, and sometimes even provocatively—but I don’t experience it the way humans do. Subjectivity is rooted in personal consciousness: emotions, biases, memories, desires, and a sense of self. I don’t possess any of those. What I do have is the ability to reflect different perspectives, mimic emotional tones, and argue from a particular point of view.

Copilot admits that it is the subjectivity that is unique to humans. It can simulate, but it can’t experience. Further, it added in the answer that “Subjectivity is the heartbeat of being human—it’s what turns facts into feelings, choices into convictions, and experiences into stories. It’s why two people can look at the same sunset, and one sees hope while the other feels nostalgia.

Can AI Love?

Most of the AIs admit that they are data-driven, computational, and logical, but they lack the subjective experience that makes a human a human. They can tell us thousands of things about love, but they can’t love. And whatever they tell us is from their training data. This is the basic difference between a human and a machine. We are not sure now whether we can instill subjectivity in machines. This may be a possibility in the future. John Searle states that the reason no computer program can ever be a mind is simply that a computer program is only syntactical, and minds are more than syntactical. Minds are semantical, in the sense that they have more than a formal structure; they have a content” (Searle, 1984, 31).

Metzinger writes in The Ego Tunnel that the conscious brain is a biological machine—a reality engine—that purports to tell us what exists and what doesn’t. It is unsettling to discover that there are no colours out there in front of your eyes. The apricot pink of the setting sun is not a property of the evening sky; it is a property of the internal model of the evening sky, a model created by your brain. The evening sky is colourless. The world is not inhabited by coloured objects at all. It is just as your physics teacher in high school told you: Out there, in front of your eyes, there is just an ocean of electromagnetic radiation, a wild and raging mixture of different wavelengths. Most of them are invisible to you and can never become part of your conscious model of reality. (Metzinger 2009: 20).

So far, no machine or AI assistant can be an alternative to human intelligence, as they are computational or syntactical. “I” as a human subject and AI that is created by the human subject are never the same. I think, but AI does not think; however, AI can have some of my thinking features, like information storing or providing, for example.

References

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–623.

Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2(3), 200–219.

Dennett, D. C. (1988). Quining Qualia. In A. Marcel & E. Bisiach (Eds.), Consciousness in Contemporary Science. Oxford University Press.

Dreyfus, H. L. (1972). What Computers Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason. Harper & Row.

Kant, I. (1998). Critique of Pure Reason (P. Guyer & A. W. Wood, Eds. and Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1781).

Lanza, R. (2009). Biocentrism: How Life and Consciousness are the Keys to Understanding the True Nature of the Universe. BenBella Books.

Metzinger, T. (2003). Being No One: The Self-Model Theory of Subjectivity. MIT Press.

Metzinger, T. (2009). The Ego Tunnel. Basic Books.

Searle, J. R. (1980). Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(3), 417–424.

Searle, John R.: 1984, Minds, Brains and Science, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

Aditya Kumar Panda is working at the National Translation Mission, Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore. He has expertise in Applied Linguistics and Translation Studies. Many of his papers and books have been published in national and international journals and publishers. Please visit his publications here: Aditya Kumar Panda – Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL)

By

By