Lopamudra interviews Sreetanwi Chakraborty, a poet, academic, and publisher, who reveals her

literary secrets, novella journey, and more. A Different Truths exclusive.

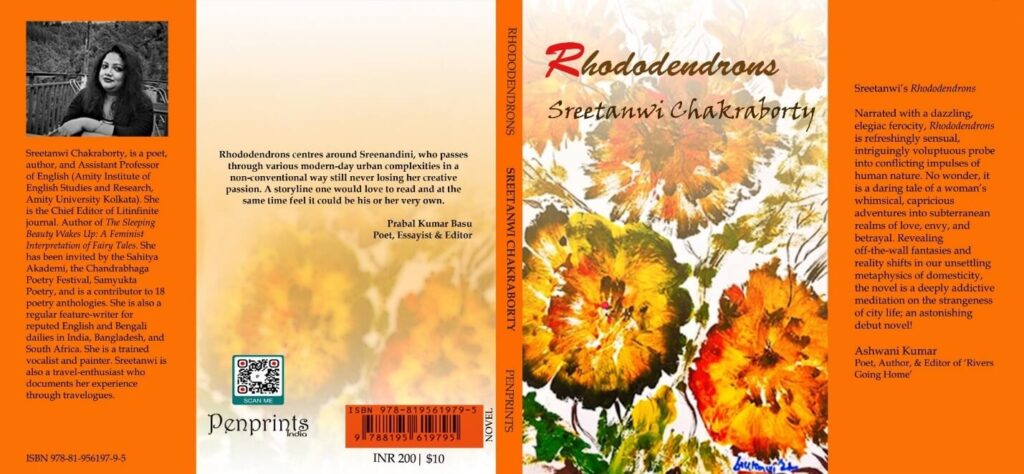

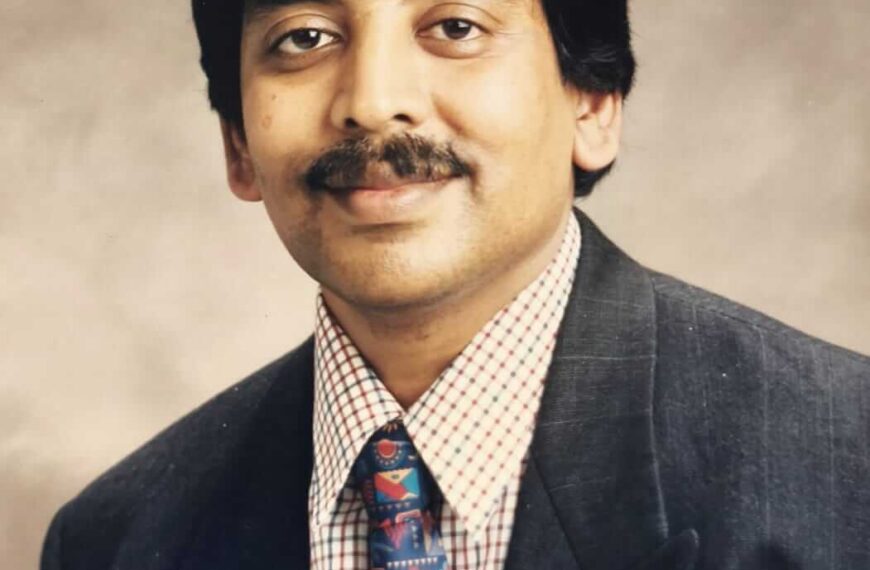

Sreetanwi Chakraborty is a multifaceted voice in literature, known for wearing many hats. She is an Assistant Professor of English at Amity University Kolkata, the Chief Editor of Litinfinite Journal, and an accomplished poet and author. Her recent publications include the novella Rhododendrons and the poetry collection Medusa Says it All, alongside scholarly works like The Sleeping Beauty Wakes Up. I first encountered Sreetanwi’s work a couple of years ago, and we recently reconnected when she edited my debut Bengali poetry collection, ‘Draupadi Theke Nijoswi: Amra’ (2025). Building on this connection, I had the pleasure of planning this candid conversation to discuss her acclaimed novella, her unique literary identity, and her insights as a publisher in Kolkata. We hope her perspectives resonate deeply with our readers.

Lopamudra Banerjee: Welcome to this heart-to-heart conversation series with authors and creative artists that I have the pleasure and honour of curating, Sreetanwi! Since our interaction that started during the times of Covid-19, to be precise, during Kolkata Book Fair 2020, I have known you to be a very serious and eclectic author and academic person, and now that I have read your much acclaimed debut novella Rhododendrons that is centered on Sreenandini and her emotional trysts and travails, I see a chunk of your persona in her, your fictional creation. What is your own perception of someone as mysterious and enigmatic as Sreenandini? What do you think inspired you to pen her journey in the novella?

Sreetanwi Chakraborty: Thank you for this wonderful introductory greeting and the insightful questions you have asked, on Rhododendrons. I have been writing Bengali and English poems since my school and college days, and thereafter, I started visualising and composing a few of the narratives for a novella. I am a typical Gemini, mercurial and whimsical as a creative writer in my temperament. Discovering parts of my own vulnerability and meandering across faces, events, torrential phases of love, despair, desperation and self-integration all around me enabled me to frame the character of Sreenandini. Complexities of relationships and an incessant quest for multiple shades of love have always intrigued me, both as a silent observer and as a writer/artist. Sreenandini, to me, appeared to be a bundle of contradictions, jostling with the mundane and the exotic. The physical, the social and the psychological – these three perspectives were my prerogative. For me, Sreenandini was not a superwoman but a lost soul of the bygone days, born untimely, yet to bloom into love, just like how she recognizes herself across places in “Kolkata where trickles of life blended with the deadliest terrains of the Park Street cemetery, trinkets of

conversation, memories meandering across generations, chocolate delights, cookies and finely chosen coffee beans, reviving the aroma of long-lost nostalgia of her school and college days.” (Chakraborty 12) To elaborate, what is coming to my mind now is the line from An Introduction ~ ‘I am sinner, I am saint’, by one of my favourite poets, Kamala Das. For me, watching the roller-coaster ride of Sreenandini and participating in it was a lifetime experience. And so am I reported by many of the fondest readers.

LB: As a poet, the title of the novella Rhododendrons seems to me like a conscious, lyrical choice of yours. How do you think the title fits into the structure of the novel, as all the chapters have unique names of their own, combining human and natural elements?

SC: I would love to share an interesting fact here. I painted the cover myself, long ago, before I wrote the novella. The kaleidoscopic vision through the acrylic petals and the sight of the rhododendrons in the misty trek routes of India encouraged me to combine the human and natural elements. I always find a strange melody in the contrarities and similarities in human nature and nature outside, the environment that nourishes and nurtures the being, the environment that might destroy the being. The supine afternoons in Park Street, with the smell of Parijatham and the melancholy tune of the flautist, the coffee house, ishtehar, vermillion, sunset, the interlocutor, mouth organs – they appeared conspicuous before my inward eye, an imaginative vision that had lyrical quality, grace, rhythmical grandeur and yet, was steeped into a sense of gorgeous simplicity – like the “half-eaten lollipop in a child’s hand.” (Chakraborty 52)

LB: In terms of the plot and trajectory of the novella, I found Rhododendrons very intriguing and lyrically charged as the protagonist moves from the coastal environs of Chennai to her abode in the city of Kolkata, her bygone days amid the turbulent political surroundings of Presidency College, again to the quaint, mystical hillside in Darjeeling where her romantic, frenzied self loses itself in wild abandon. Was it an amalgamation of both a personal and universal mindscape? What are your thoughts?

SC: Yes, I fully adhere to the fact that it was an amalgamation of a personal and a universal mindscape. I published my edited e-book on travel literature, Trouvaille, a few years back. For me, travel is not just about discovering external environments, trails, and spaces. But it is the excavation of a whole new culture and customs, getting myself attuned to the place like the fluttering pages of a poem, and then establishing a quaint mental connection with it, in all its varied hues, hullabaloo, and reticence. For me, writing the phases of Sreenandini’s life, where she is the pivot of all relationships, was both the frenzied ‘self’ losing itself in a sense of wild abandonment and simultaneously a wild abandonment losing itself in the frenzied self. It is a careful orchestration of the sheer, ineluctable vacuity in her life along with moments of ecstasy.

LB: The politically charged intellectual environs of Kolkata, especially of Presidency College, which constitutes a part of Sreenandini’s student life, the strife that she was subject to in those days later merges with her journey in Darjeeling with almost a surreal feeling of déjà vu. Are some of those narratives about Kolkata somewhat shaped by your own academic life and perceptions during your student life?

SC: Yes, you can say there are ample autobiographical elements. I scored well in the admission test and secured a fine position in the merit list of Presidency College in 2004. My English Honours years (2004-2007), my Charuchandra Ghosh Memorial Prize, tones and hues of my academic experience and how I experienced my growth from adolescence to adulthood, smelling books in the Presidency library, engrossed in the class lectures, walking through the empty corridors during late evening hours, Pramod da’s canteen, politics, leaflet-making, sloganeering, coffee house and adjacent areas, and whatever I learnt in the classroom and beyond. And thereafter, the experience continued at Calcutta University during my higher studies, and thereafter, research happened. My academic and research pursuits, working in Salesian College in Siliguri and in the Sonada area, gave me ample time to interact with nature and a less claustrophobic environment in several ways. So, I believe I have been gallivanting for a long time, and these moments have created a literary collage, active and prominent in their own merits.

LB: In its essence, the novella, I believe, is both an inward and outward journey that defines Sreenandini in relation to the men in her life. What is the vision of this journey with which you crafted those chapters?

SC: It would be a travesty of truth if I did not recall Sylvia Plath’s Mad Girl’s Love Song today, again, one of the very few women poets who has disturbed the very kernel of my emotional set-up – “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; I lift my lids and all is born again. (I think I made you up inside my head.)” Is it not Afroz? Is it not the tenacious Baishakh, the husband in Sreenandini’s life? Is it not the making up of a fairytale world with Amudhan? But then again, like bedazzled bubbles in a distant dream, passions keep appearing and reappearing in her stages of moonlight sonata. Fragmented, half-eaten, sonorous and yet gentle, a sense of a surging and ebbing desire, and the artistic hooliganism of emotion – that is exactly how I wanted to articulate Sreenandini’s journey.

LB: From your novella, Rhododendrons, we are now moving to your diverse literary repertoire, which also defines you. Your literary and academic journey has covered many genres–you have been an acclaimed author, poet, editor of an academic journal Litinfinite, the co-founder and editor of one of the publishing houses of Kolkata, Penprints Publications, and above all, a Professor of English literature at Amity University. I’m curious to know which of these identities resonates the most with your persona, or if your

Life shaped in equal measures by all these facets of your journey?

SC: I am exactly what I have posted on my social media status – creatively eccentric or eccentrically creative. As an academic, as a writer, editor and publisher, it is very difficult to switch roles, but yes, I try. Art and literature, creative writing and painting are the foods for my soul, sometimes in the form of abstract ambiguities when I cry, laugh, and experience mood swings, and yet, I become pregnant with words, images, and an intense creative zeal. Academic prospects and jobs are important for monetary benefits, erudition, and fulfilling my bucket list of travel destinations. And yes, I love my work as an editor for an academic journal that is indexed in more than 275 global libraries and has received some of the top indexes in the field of arts and humanities. To be extremely partial, yes, Penprints is our dream project; a major part of me has evolved because of the learning experience I went through as part of the Penprints team. So, in a way, my life is shaped in equal measures by all these facets. Not a single role can be relegated to the background.

LB: Besides being a prolific writer and poet, you are also a beautiful artist and painter, and I have seen many book cover designs and artworks created by you that have embodied your creative passion, in my understanding. Can you tell the readers about some recent artwork projects that you were a part of, including book covers, that were intellectually and artistically stimulating to you as an artist?

SC: I was a student of eminent painter Rekha Chakraborty for a very brief period during my school days. Ashok Ganguly sir and Subhankar Bose sir from my school, and my art teacher Barun Chakraborty taught me colour mixing (water, oil, acrylic), lining and lino print arts, mixed media, collage, sketches, leaf painting, clay art, and more. My sister, Sreetapa Chakrabarty, who is an assistant professor of Political Science, is a fabulous painter, and I also draw my inspiration from her. I have done an invited cover design for Prachi Journal (Sahitya Akademi) in 2023, was invited as an artist and writer by Creative Leaves, and designed some of the major covers for Penprints and a few of the Bengali publications in Kolkata. I used a round brush and acrylic on chart paper for drawing the cover of Rhododendrons. The painting, as I said before, was done much earlier, and I wrote the novel later, sometimes musing on all those stories that the painting depicted.

LB: Can you tell me how tough or how stimulating it is to be a bilingual writer, publishing your creative writing in both English and Bengali, your mother tongue? Do the nuances of both languages stimulate your creative expressions, and are they influenced by any conflicting impulses to delve into the complexities of human language? I am asking this as a bilingual writer myself, as I am intrigued by the idea. What are your thoughts on it?

SC: This is an excellent question. I cannot deny the fact that both Bengali and English have made equal contributions in shaping and encouraging my creativity. It is difficult to deal with some of the nuanced patterns in both languages all the time, and I experienced some of these conflicting impulses while translating a short story, Insatiate Desire in The Collected Short Stories of Kazi Nazrul Islam (Orient Blackswan 2024). The diversity and the dichotomy in both the languages and their expressions, tones, rhythmic conjectures, and multilayered delivery options often give rise to a sense of cleft in how we think and what exactly we produce. So, yes, although I am not petrified by these complexities, I do serious research on my part whenever I am badly stuck.

LB: Imitation is an art, according to a classical/Renaissance concept discussed in literary studies. Are you a believer in this idea in art? If so, do you agree that your unique style of writing has influenced any writer in our contemporary times? Also, which classic poets and authors inspired you in your own creative journey?

SC: I believe any kind of voracious reading in any language that we are comfortable in creates a profound impact on our lives. Any form of art, be it writing or performing arts, all in their truest sense, is both imitation and invention—a mirror that reflects life yet refracts it through the artist’s soul. My writing, though rooted in observation, seeks to transform the ordinary into something luminously alive. If my words have touched or shaped the consciousness of a contemporary voice, it is but the natural ripple of shared sensibilities.

I owe my creative awakening to the timeless grace of Tagore, Swarnakumari Devi, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay, Mahasweta Devi, Ashapurna Devi, Maitreyi Devi, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Jibanananda Das, Bhumendra Guha, Manindra Gupta, Sandipan Chattopadhyay, Bhaskar Chakraborty, Buddhadeb Guha, and many others. In English, I admire the major romantic and modernist poets and novelists (Shelley, Keats, Eliot, Joyce, and Woolf, the list will go on). Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, Sylvia Plath, and Maya Angelou in American literature, Kamala Das, Ismat Chughtai, Amrita Pritam, Shashi Deshpande, Nayantara Sahgal, Githa Hariharan, Arundhati Roy, Temsula Ao, and many more. Among some of the brilliant contemporary Indian writers, I feel deeply encouraged by the works of Sanjukta Dasgupta, Arundhathi Subramaniam, Sumana Roy, and Bhaswati Ghosh. I am a huge fan of Murakami, Pamuk, Rushdie, and Amitav Ghosh. In fact, every reading and any reading comes with an addition to the list of favourites.

LB: Previously, there was no social media to showcase the works of any, yet the genre of poetry brought popularity to many eminent poets. This became possible for the high-quality journals and literary magazines that were produced during those heydays of literary excellence. What is the scenario at present, both in print and on social media?

SC: Indeed, the earlier age of poetry thrived not on algorithms but on aesthetic integrity—where journals and literary magazines were sanctuaries of thought, nurturing voices that shaped the very texture of modern literature. Today, the landscape has metamorphosed. The printed word still endures in select, discerning circles—through independent publishing companies and curated anthologies—but the pulse of poetry now beats vividly across social media, where verses travel faster than ink can dry. Instagram, podcasts, and digital journals have become new-age salons, offering instant readership and democratized expression. Yet amidst this abundance lies both blessing and peril—the ease of expression sometimes diluting the art’s depth. Still, poetry survives and transforms; its soul unbroken, only its stage expanded. The poet of today, balancing tradition and technology, wields not only the pen but also the pixel—ensuring that poetry remains eternal, resonant, and profoundly human.

LB: Indeed, such thoughtful and reflective answers, touching the whole gamut of your literary work, also touching upon your love for literature and your passion for publishing, editing and the creative arts! Young, enterprising and deeply meditative minds like yours need to be celebrated increasingly, and this interview was a small step of mine towards that direction. I wish all the best to your future literary and artistic endeavours.

SC: I enjoyed this tete-a-tete. Thank you.

Photos sourced by the interviewer

Lopamudra Banerjee is a multi-talented author, poet, translator, and editor with eight published books and six anthologies in fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. She has been a featured poet at Rice University, Houston (2019), ‘Life in Quarantine’, the Digital Humanities Archive of Stanford University, USA. Her recent translations include ‘Bakul Katha: Tale of the Emancipated Woman’ and ‘The Bard and his Sister-in-law’.

By

By

By

By