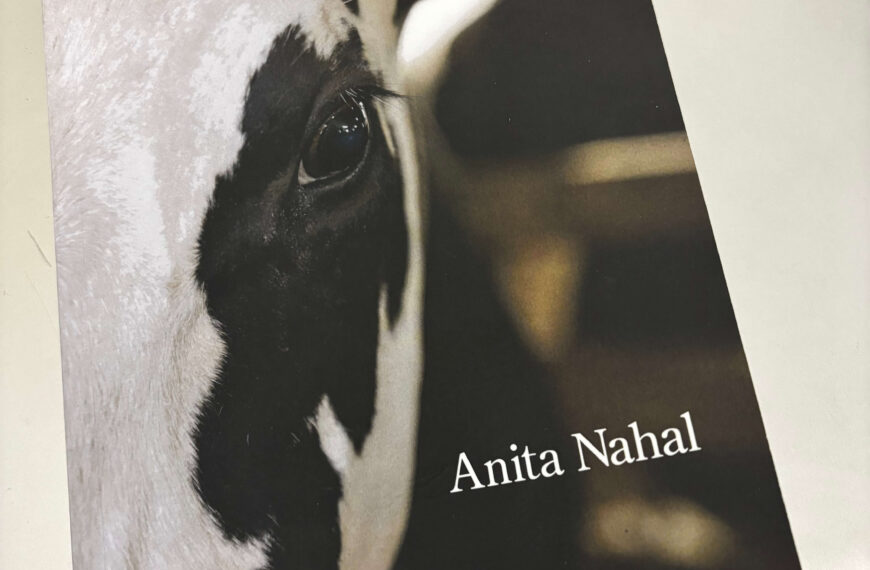

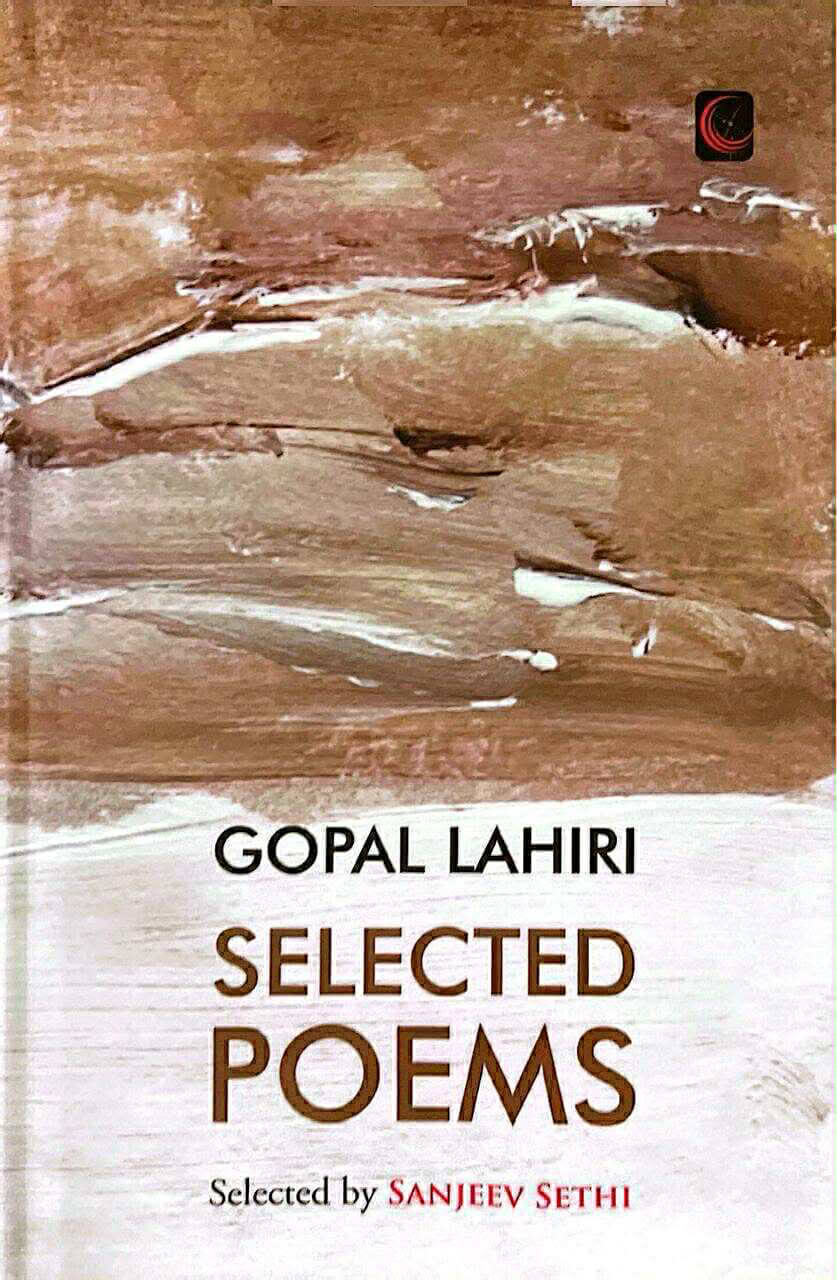

Uncover the powerful trinity: Lilith, Radha, and Bhanumati. Gopal Lahiri’s poetry explores these legendary women, merging myth and the modern psyche, for Different Truths. A review by Duane.

Lilith. Radha. Bhanumati.

Aside from a few place names, Gopal Lahiri mostly avoids personal nouns. Except for three mythological/literary females, he only addresses anonymous second-person figures. Although they all seem to have ancient pedigrees, none of them really emerged in their present form until about a millennium ago. Since then, they have come to represent a feminine trinity: Lilith has come to embody lust; Radha, love and compassion; and Bhanumati, dutiful passivity.

In brief, though Lilith’s name was perhaps derived from Akkadian and Hebrew epithets, she made no appearance in the Bible itself, although, ca 500, some characters with that name but with various attributes began to appear. Eventually, however, the medieval Alphabet of Ben-Sira identified her as Adam’s first consort, and she began to solidify into a full-figured she-demon. Unlike Eve, who was taken from Adam’s rib, Lilith was made from the same clay as Adam himself, at the same moment of creation, making them, in her eyes, equal beings. She refused to submit to his dominance and left him. For this, she was cursed to strangle her own offspring until she returned to the Garden of Eden.

Refusing to do so, she evolved into a demonic paramour who was feared in Jewish folklore as a baby-killer. Radha, a major Hindu deity, also only fully manifested herself around 1100 CE. Her adherents claim that she was, all along, the secret treasure within the Vedic scriptures; though ubiquitous as Krishna’s consort, she exhibited but differing roles, manifestations, and descriptions. Her current depiction owes to Jayadeva’s play Gita Govinda, in which she is abandoned by Krishna, but he is restored to her due to her steadfast devotion. In the Mahabharata, Duryodhana defrauded his cousins of their rightful kingdom and ruthlessly led his hundred brothers against them, despite Krishna’s peace efforts. In the epic, he had many unnamed wives, though later accounts invented various consorts for him. However, it was not until the 11th century or thereabouts did Bhatta Narayana composed the play the Vanisamhara that introduced Bhanumati as his sole spouse; since then, she has universally assumed that role in popular and even some scholarly accounts.

Perhaps the thrust of this review is misguided, since it is based on a sampling of poems from Lahiri’s five collections. A fuller consideration may well negate the idea of these women’s exclusivity. Volumes that reprise a poet’s accomplishments are generally labelled “Complete” (“all” available poems), “Collected” (those which the poet included in the books, but which may exclude scattered poems from periodicals), and “Selected” (the most variable of the three, since we usually don’t know why they were chosen or by whom).

In this case, however, the selection was made by Sanjeev Sethi, a fellow poet with longstanding and ongoing familiarity with Lahiri’s oeuvre, a “celebration of images,” in his own phrase. However, as Sethi admits, “Every time I chose a piece, I could hear a plaintive cry: Why not me?” For his part, Lahiri believes that such a retrospective should provide “a fair reflection of the poet’s evolution, growth, and development.” He notes that much of his work is concerned with nature and “how our physical world and selves are continually drawn toward disbanding and dispersal.”

In my own view, his poems, overall, are philosophical and introspective. They are manifestations of nature in the abstract rather than the particular, of the individual psyche in relation to the social environment. The first poem in the collection, “Crossing the Shoreline,” uses beach imagery to embody sleep, and many succeeding pieces follow the same pattern of using the external world to reveal the inner world. “Every location,” as he says, “is within walking distance.” The volume closes with a series of his beloved haiku, ending with the particularly poignant “winter rain/weaves the lost skin / a sharp blade.”

But I wish to concentrate on the three short poems that feature his heroines (“Lilith in You,” “Semaphore,” and “Bhanumati”) as exemplifying his insight, his technique, and even his attitude toward poetry. In the first example, he is addressing an unnamed “you,” likened to Lilith; in the second, he only obliquely references the goddess by saying old ladies accompany their task of filling their pots with water by “humming perhaps the Radha ballad” (is it a devotional chant? a recent pop song?). In the third poem, the poet assumes the persona of Bhanumati herself.

Unlike most poets through the ages, Lahiri does not produce many love songs. However, he does compare his poetry, in lover-like expressions, to Lilith herself, saying he loves “your darkness dipped in black ink …. your illusions, your freedom of magic” and notes “all that / tortures turn into a touch of feather-soft palms” and “the warmth of my desire rewrites in water lilies.” Similarly, in another poem, he remarks that “a line is often left hanging to suspend in desire.” He notes that “our shadows are sliced in equal halves” in old black-white photos, but laments that “the birds can’t unfold their wings” in “your silent talking” and that he lives in his lips (“I taste your lips, a tremor in you”) and smooths away “long scars” with “starry nights” that roll continuously like a cobblestone; “sound is a diversion.”

He tells his Lilith poem, “I seek your spirit in every woman,” but Bhanumati is no longer the poet but the long-suffering embodiment of the eternal woman, with the aid of Krishna in her heart to allow her “to say without saying it.” Her husband regards her body as a garment; “he loves war, he wants to fight against his brothers, / I want to carry my heaven with me elsewhere.” She laments the “thousand years of mothers and daughters, / girl after girl grieve in silence, / not anymore to lie beneath men.” She closes by conjuring “new palettes and brushstrokes.” (In another poem, Lahiri imagines “a gloomy palette in which the children grasp.”) Her husband finds only cold shoulders, cruel looks, what else can I say even after giving myself?” Like Lilith’s, her “monstrous eyes / resonate in a stream of sorrow.”

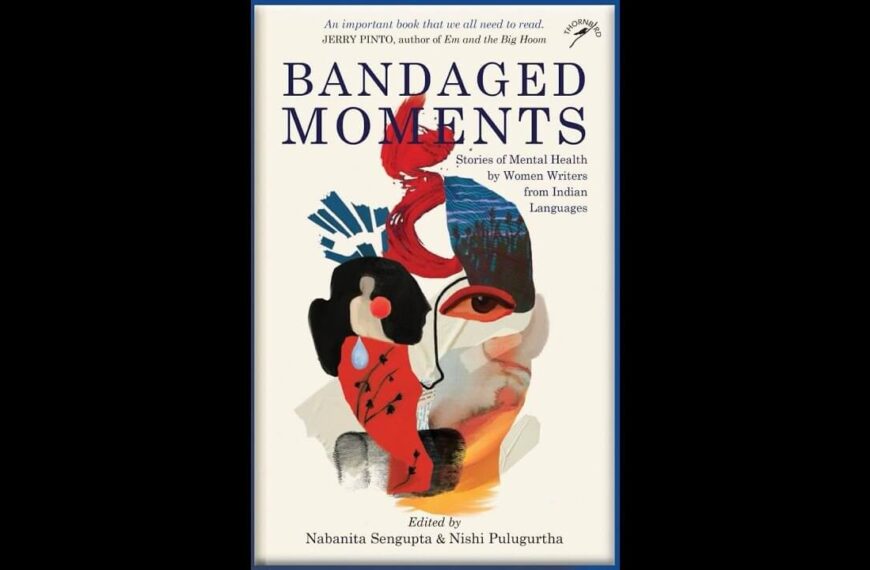

Cover photo sourced by the reviewer

Duane Vorhees is an American poet living in Thailand. His most recent occupation was teaching American literature and other subjects for the University of Maryland in Korea and Japan. A PhD in American Culture Studies, Cyberwit has published two of his recent poetry collections in India, and Hog Press, six in the US.

By

By

By

By

By

By