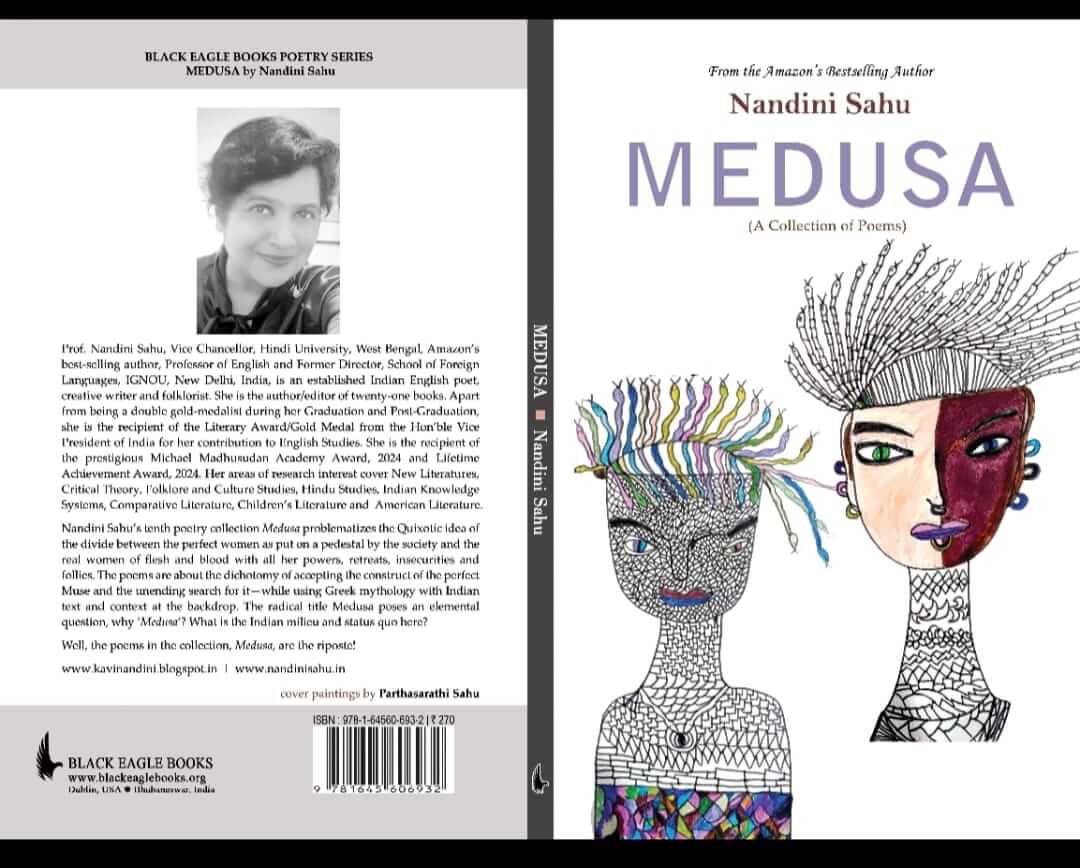

Swara reviews Medusa by Nandini Sahu weaves myth and modernity, transforming Medusa into a symbol of empowered, authentic womanhood.

Medusa, by the acclaimed poet, folklorist, and academician Nandini Sahu, depicts a powerful poetic journey that blends the binaries between tradition and transgression, silence and articulation, and myth and modernity. Medusa is a diary of the soul, an archive of the subconscious mind, a song of womanhood, of exile and homecoming. These poems are not just artistic creations but lyrical interventions that engage with feminine agency, personal loss, and cultural memory.

As the title suggests, the mythical figure of Medusa serves as the central metaphor of the poetry collection. In fact, the collection tries to transform the maligned and misunderstood figure of Medusa into a symbol of the imperfect, real woman who has been denied narrative control so far. Poems like “Sisterhood”, “Tapoi”, “Time Was All He Had”, “The Difficult Daughter”, “Letter to My Unborn Daughter”, and “The Akshayapatra in Jagannath Puri” reflect the transition of the feminine voice into poetic resistance.

“Sisterhood” celebrates shared feminine experiences that go beyond personal grief. It evokes a solidarity among women who have been “Medusas”, and suggests a reclaiming of womanhood that is vilified. Inspired by mythic and modern sensibilities, the poem unites wounded daughters in a mutual recognition of loss, survival, and strength. The diction has political undertones but is intimate at the same time. There is a shift in tone from melancholic reflection to fierce assertion, which also highlights the poet’s aesthetic vision.

From the suffering Medusas, the poet shifts the focus to a specific figure of Odia folklore in “Tapoi.” She reconfigures the symbolic figure of suffering and silence and revisits the traditional tale to interpret it from a contemporary feminist perspective. The story of Tapoi, a woman betrayed by her sisters-in-law and saved by her brother, becomes a canvas for the poet to work on and consciously rewrite the archetypal experience of a girl wronged by patriarchy and eventually vindicated. The poem serves as a bridge between oral tradition and literary activism.

Returning to a subject that is personal and poignant, “Time Was All He Had” serves as a eulogy by a daughter to her late father. Time becomes both relentless and redemptive as a spiritual presence in the poem. It claims life like an antagonist, as well as creates memories that heal. The tone of mourning and quiet reverence is expressed through visual imagery. However, the poem is not just a personal reflection. The emotions expressed through the personal narrative lend it a universal quality.

In the next poem, “The Difficult Daughter”, the poet addresses one of the most pressing concerns of society- the imposition of expectations on women by patriarchy. It critiques the labelling of women who deviate from norms as “difficult.” It is a poignant expression of the oscillation between a woman’s emerging self-worth and her internalised guilt. The words express the psychological toll of feeling “othered” by one’s own family members. The poem puts forward a pertinent question- “Why must a daughter’s worth / be measured in obedience?” It addresses larger issues of the expected subservience, rigid gender norms, and the contribution of women in reinforcing patriarchy.

Continuing the theme from a different perspective in “Letter to My Unborn Daughter”, the poet articulates her dream for an unborn child who is free from the burden of gendered expectations. The unborn daughter becomes a repository of the hopes that have remained unfulfilled for several generations. The poet urges her to reclaim her voice and use her vulnerability as her strength. She cites exemplary figures like Kali, Lakshmi, and Tara as role models for the daughter. This imaginary idealisation of and address to the unborn daughter is emotionally stirring as it insists on authenticity in a world that imposes roles.

Ending the poetry collection with “The Akshyayapatra in Jagannath Puri”, the poet focuses on Draupadi’s divine vessel, the Akshyayapatra, as a symbol of resilience and abundance. It goes beyond being a divine miracle and becomes a metaphor for emotional replenishment. The spiritual side of feminism is evident in the poet’s approach, which is rooted in Indian knowledge systems and opens up the age-old story to pluralistic interpretations. Set in Puri, the location not only serves as a site of religious devotion but also a space for introspection and ancestral remembrance.

These beautiful poetic expressions offer just a glimpse of the vast repository of over 40 poems in the collection Medusa, which showcases Prof. Nandini Sahu’s remarkable range and ability to weave verses around a central metaphor. Notable poems like “An Ode to Every Woman”, “What My Mother Doesn’t Know,” and “Boys Don’t Cry” question stereotypes surrounding gender.The collection holisticallynavigates grief, generational trauma, loss, and healing while probing silences surrounding femininity and masculinity. As a woman, scholar, and daughter of Odisha, the poet creates “living poetry”, which is courageous and authentic. This poetic endeavour is a vital cultural document that invites conversations on gender, mythology, and contemporary Indian English poetry.

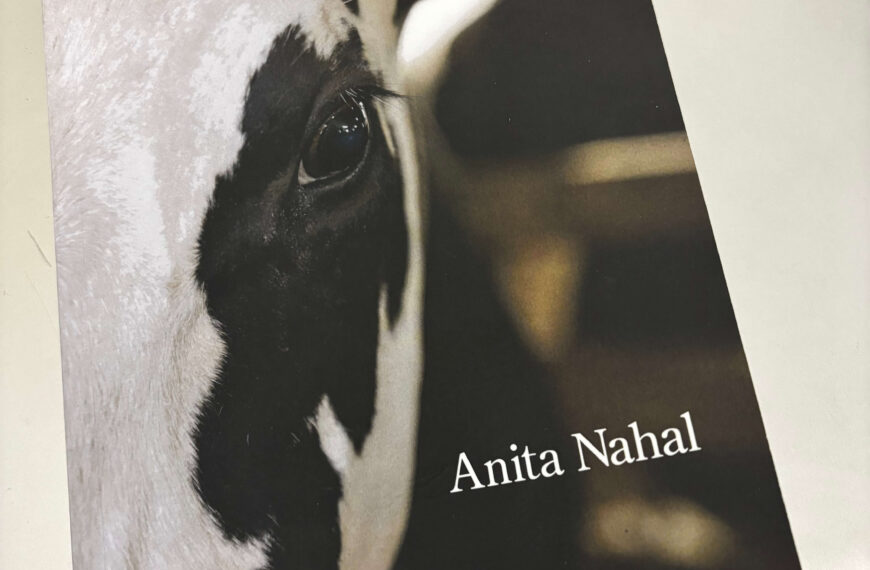

Cover photo sourced by the reviewer

Swara Thacker serves as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Foreign Languages at SVKM’s Mithibai College, Mumbai. She is also a research scholar specialising in modern and postmodern literature, with a particular focus on popular culture and its intersections with literary studies. She has presented her research at various national and international conferences and is currently completing her doctoral thesis.

By

By

By

By

By

By

thanks for the review, will definitely try it out

Excellent work, it’s Diverse, short and compact in describing feminism impactfully.Wonderful crisp review.