A cinematographer, Anoop’s relation with the visual medium is deep. He had prepared a detailed project report, to produce a documentary on Tagore’s painting genius. Unfortunately, his partners abroad were unable to procure the necessary funds. Though the documentary project was canned, the author shared his in-depth research with us. Here is a special feature, on Tagore, exclusively

for Different Truths.

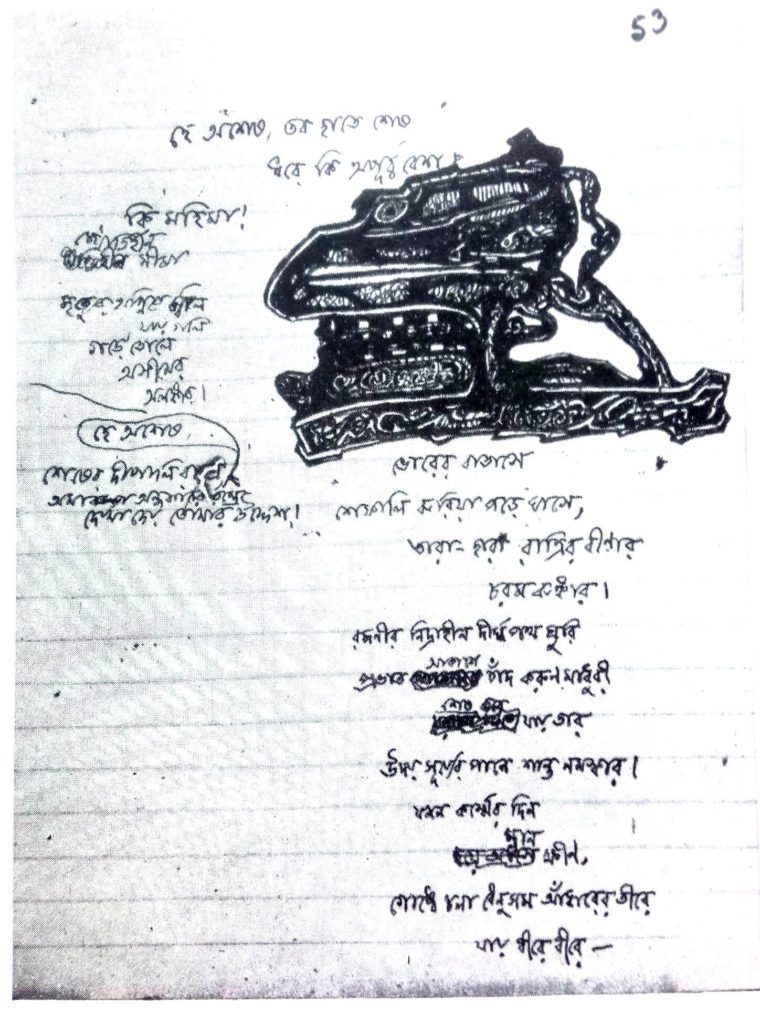

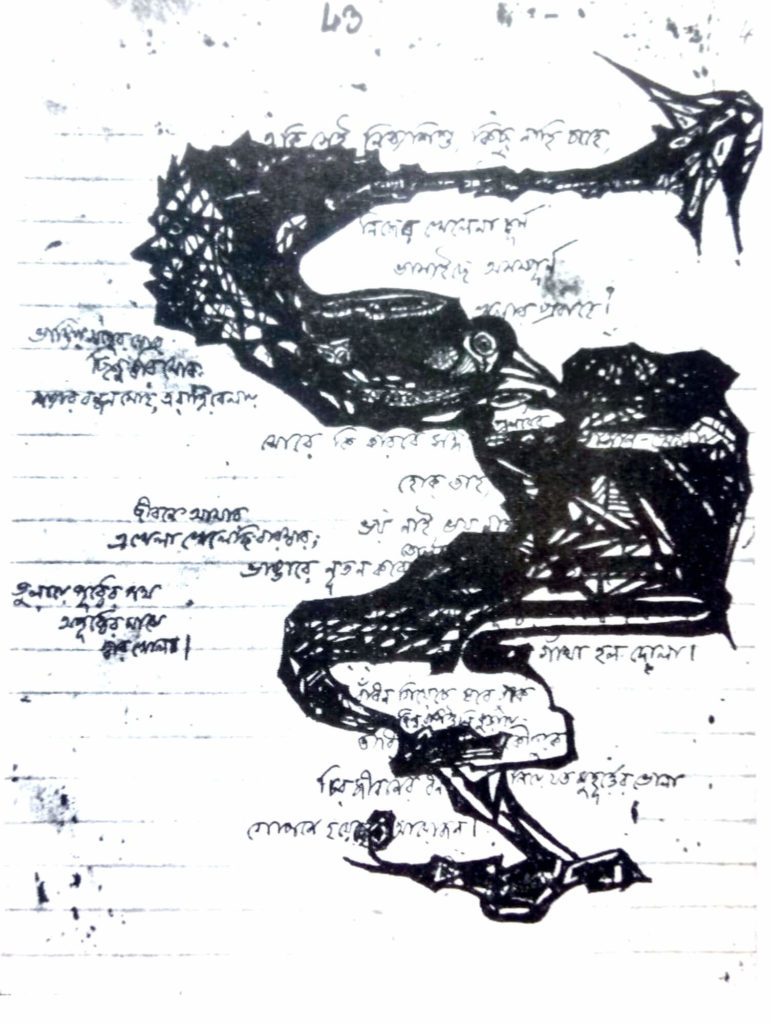

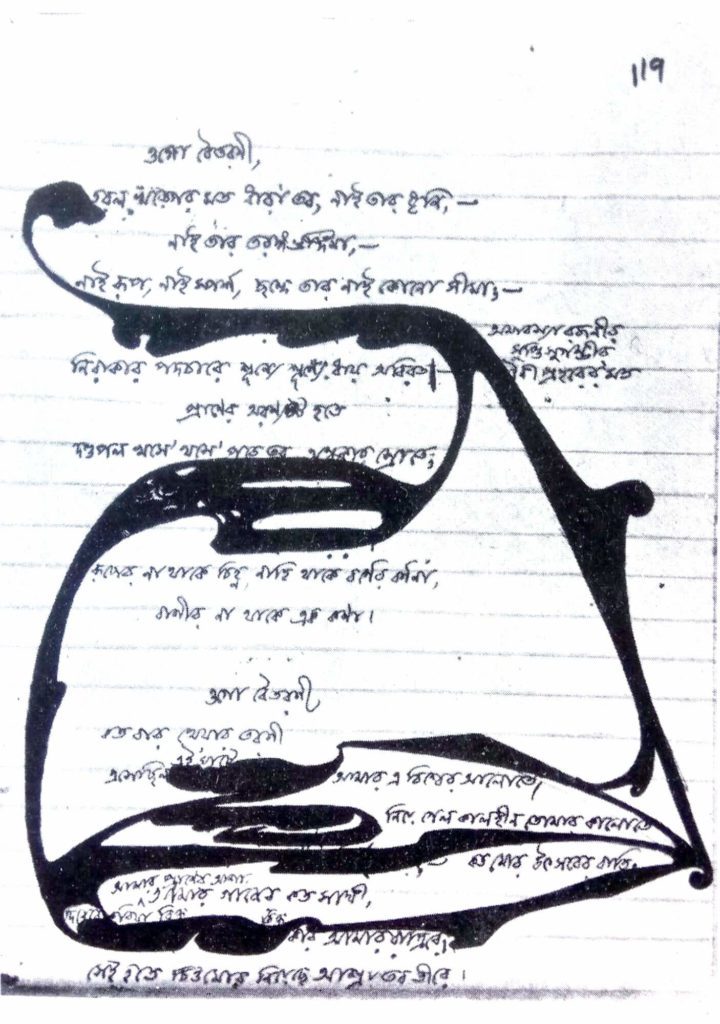

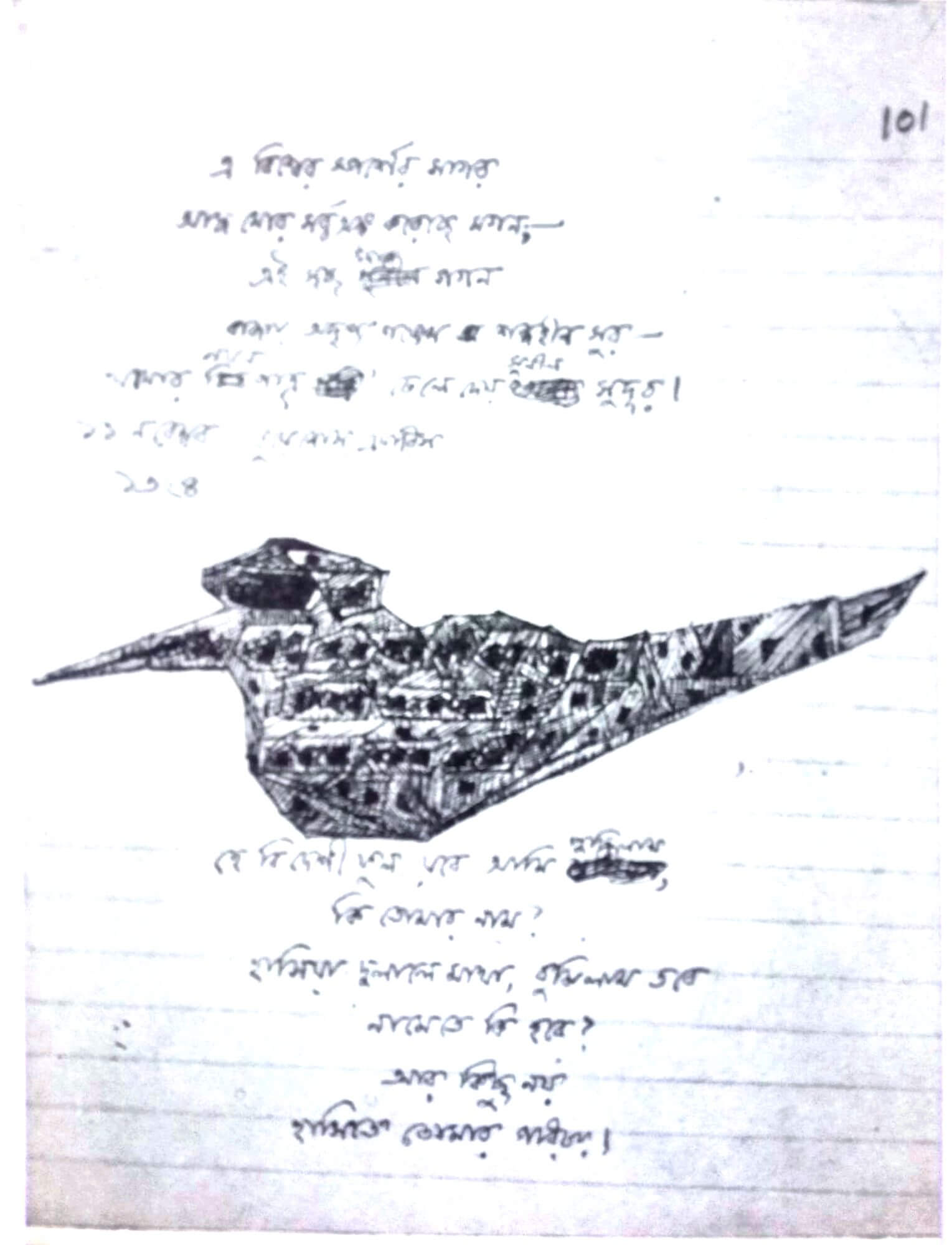

In January 1993, I visited Shantiniketan in West Bengal. Shantiniketan is the realisation of the ideals of a visionary educationist, who believed in cultural synthesis and the overall development of the individual in harmony with nature. The Ashram which Tagore began, in 1903, with merely four or five students is now a full-fledged University of international repute, where the accent is especially on art, music, and cultural activities. While going through the art gallery of the Rabindra Bhavan Museum, I had the rare opportunity to see the personal diaries of Gurudev Tagore. While holding it in my hands, I felt an inner vibration as if the poet himself was speaking to me, and thus going through the pages I noticed that most of these writings were accompanied by scribbles that had organic and geometric forms. At the first sight, there was a loss of perspective, soon as I reoriented my vision through the path of patterns, the images grew inside me and the elements merged to be one, more beautiful than the first appearance.

These scribbles are called doodles or erasures, yet these cannot be mere embellishments or illustrations as the name suggests but form an integral part of the poet’s creative process. Although not directly connected to his poetry, these doodles are important because these are his first artistic attempts, which later culminate in the impressive corpus of his 2000 odd paintings. No Indian artist, poet, or writer (except Rabindranath’s nephews Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore) has done anything of this kind.

The poet strikes off the mistakes he makes in the manuscripts; these cancellations are later joined by lines of varying thickness that flow and twist into shapes. His aversion to any sort of academic regulations (which had prompted him earlier to set up the Ashram – Shantiniketan) made him open to primitive and child art and the doodles show their influence. Tagore didn’t have any formal

training in drawing before he took up painting, which in fact comes during the late 1920s. Hence, we can deduce that these doodlings were his formal training for him to become a modern painter. If we trace it chronologically, it shows a gradual progression from simple to complex, where later the text becomes secondary. These doodles have the stamp of his ability to assimilate, and they give form to all that he has experienced into a totally new expression. Tagore’s own saying about his painting and erasures are:

“From my childhood I think I had an inborn sense of rhythm. The only training which I had from my young days was the training in rhythm, the rhythm in thought, the rhythm in sound. I had come to know that rhythm gives reality to that which is desultory, which is insignificant in itself. And, therefore, when the scratches in my manuscript cried like sinners for salvation and assailed my eyes with the ugliness of their irrelevance, I often took more time in rescuing them into a merciful finality of rhythm than in carrying on what was my obvious task. In the process of this salvage work, I came to discover one fact that in the universe of forms there is a perpetual activity of natural selection in lines, and only the fittest survives which has in itself the fitness of cadence. And I felt that to solve the unemployment problem of the homeless heterogeneous into an interrelated balance of fulfilment is creation itself….

“I find disinterested pleasure in this work of reclamation often giving to it more time and care than to my immediate duties in literature, often aspiring to a permanent recognition from the world… I need not formulate any doctrine of art but be contended by simply saying that in my case my pictures did not have their origin in trained discipline, in tradition and deliberate attempt to illustration, but in my instinct for rhythm, my pleasure in a harmonious combination of lines and colours….

“My pictures are my versification in lines…. People often ask me about the meaning of my pictures. I remain silent even as my pictures are. It is for them to express and not to explain. They have nothing ulterior behind their own appearance for the thoughts to explore and words to describe.”

We talk about Tagore’s painting, which to me is like talking about the tree and neglecting the seed and its germination. To understand the tree fully its equally important to understand the seed and its germination in which case doodling forms the shape of the seed and germination for Tagore to be an artist.

A man whom the world has known more as a literary person and for which intellectuals and institutions world over has conferred honour, with Noble Prize, Knighthood and D.Litt. to name some, but the other equally masterly genius work of his was not very much taken seriously in comparison to his literary work. The effort is to bring out the equally important element of a modern painter in Rabindranath Tagore who was unique and original in his own way. As has been aptly said by Andrew Robinson:

“When Tagore took to painting in late 1920’s he was approaching seventy and was already recognised as one of the world’s remarkable men. He made contributions in every field- artistic, educational, religious, and political. Although entirely untrained, he was able to draw upon his wealth of experience and imagination to works that startled both Indian and Western artists and critics of the time with their freshness and directness of feeling. They seemed to bear little relationship to the rest of his oeuvre or to Indian or Western Art.”

By his death, in 1941, Tagore had produced over two thousand paintings and drawings, several hundreds of which merits being placed beside those of major twentieth-century artists. “Considering the last start, this makes for an astonishing output of great fecundity,” writes Satyajit Ray. “It is important to stress he was uninfluenced by any painter, eastern or western. His work does not stem from any tradition but is truly original. Whether one likes it or not, one has to admit its uniqueness. Personally, I feel it occupies a place of major importance besides his equally formidable output of novels, short stories, plays, essays, letters, songs and music” says Ray.

Tagore had a broad range of talent. He was recognised universally as a poet, thinker, musicologist, philanthropist, and lately as a painter. His ideas and conceptions were always futuristic with a sort of semblance to the present. The unique characteristic in him was that he maintained a balance between a life of creativity and scholarship on the one hand and a life of service to fellow human

beings on the other. As Albert Schweitzer writes about Tagore, “This completely noble and harmonious thinker belongs not only to his own people but to humanity.” Here to support Albert’s statement we see that during his lifetime Tagore had a vibrant and emotional relationship with almost every part of the globe. During the period, 1878 to 1934, his travels abroad were to England, U.S.A, Japan, Burma, France, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Germany, Austria, China, South America, Italy, Norway, Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, Rumania, Egypt, Yugoslavia, Malaya, Java, Bali, Ceylon, Canada, Denmark, Russia, Poland, Persia, and

Iraq. Thus, we can easily evaluate from his tours the concern for humanity at the global level and not merely at the national level. One remarkable thing to be noted that these two thousand plus paintings, which he has done was during the period 1928-1940, while reaching an age of 67 when normally reflexes and mind tends to disintegrate in a person but because of his prolonged intellectual genius he was able to create over 2000 paintings. The point to note is Tagore first starts painting, in 1928, and, in 1930, he exhibits them in major cities of Europe, U.K., and later the U.S.A, within two years his control of the medium comes out not as a learner but as a genius.

Doodling is a part of his creativity and all through his writing process be it poems, short stories, plays, letters, etc, we find its presence interwoven in an intricate manner. The imagination and creative use of erasure/doodles, which at an initial point were used merely to strike out unwanted or superfluous words or sentences are then given form and shape which has its own evolution. During the process, Tagore finds such figures as an integral part of his writing giving a two-layer perspective, one of literary and other of form and shape. Later, such figures take over the literary dimension where images become the primary motif, leaving the writing element rather subdued. This unique process which comes naturally and reflects the emerging painting genius is worth studying by all art students because the study itself becomes a tool for all the students who wish to learn the art and modern painting.

The alchemy of this research paper is to go into the psyche of the creative process and to explore the grammar of such element, about which the poet himself says “When the scratches in my manuscript cried like sinners for salvation and assailed my eyes with the ugliness of their irrelevance. I often took more time in rescuing them into a merciful finality of rhythm than in carrying on what was my obvious task. In the process of this salvage work, I came to discover one fact that in the universe of forms there is a perpetual activity of natural selection in lines, and only the fittest survives which has, in itself, the fitness of cadence…. The language of sound is a tiny drop in the silence of the infinite. The universe has its eternal language of gesture, it tells in the voice of pictures and dance. Every object in this world proclaims in the dumb signal of the lines and colours the fact that it is not a mere logical abstraction or a mere thing of use, but it is unique, it carries the miracle of its existence.” (Rabindranath Tagore, The Noble Laureate of Literature, 1913).

The finale of such a creative process is seen in him as an urge to paint and thus culminates in a corpus of two thousand plus paintings during the last decades of his life, marking him as one of the modern painters of India.

Visuals sourced by the author from Vishva Bharti University, Shantiniketan

By

By

By

By